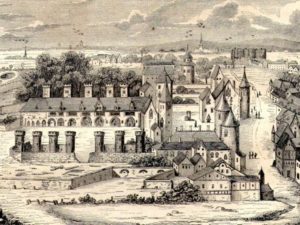

Le Palais des Tournelles

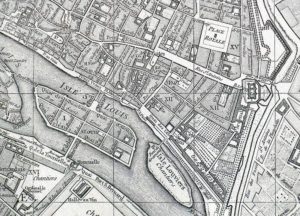

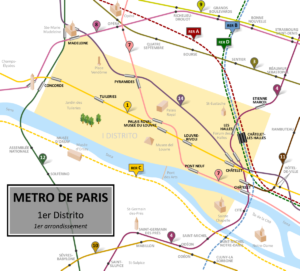

The Marais area is situated between the 3rd and 4th arrondissements of Paris. Spared by the great Haussmannian works in the 19th century, it is above all an area of exceptional architecture and there remain many magnificent manors built during the 17th century, now mainly housing museums. Originally settled on a vast marshy area, (the name Marais means “Marsh”), the district had its heyday in the early 17th century when King Henry IV decided to build a sublime place dedicated to stroll: la Place des Vosges (inaugurated in 1612).

The hôtel des Tournelles is a now-demolished collection of buildings from the 14th century onwards north of place des Vosges. It was named after its many ‘tournelles’ or little towers.[1][2]

It was owned by the kings of France for a long period of time, though they did not often live there. Henry II of France died there in 1559 of wounds he received in a joust. After his death, his widow Catherine de Médici, abandoned the building, by then quite derelict and old-fashioned. It was turned into a gunpowder magazine, then sold to finance the construction of the Tuileries, designed and developed to suit the queen’s Italian style.

Contents

Site and description

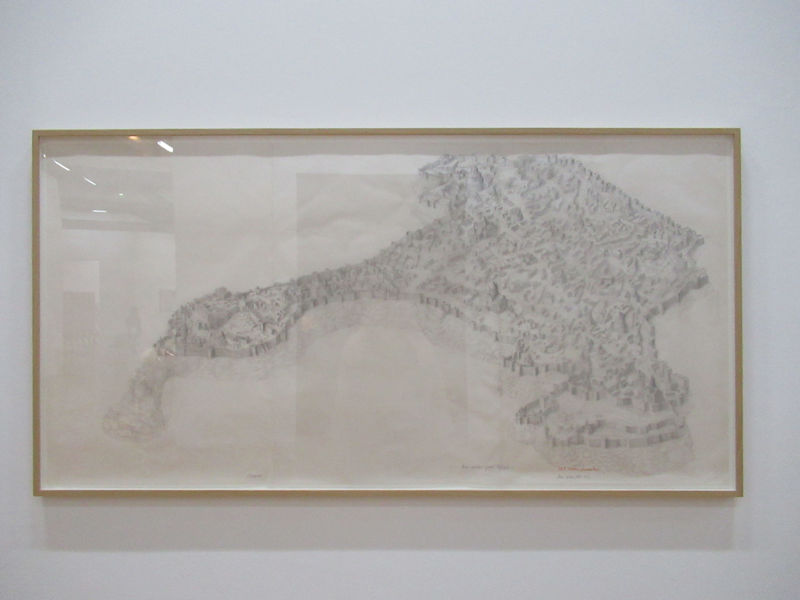

At the beginning of the 15th century, the district around the hôtel formed a huge rectangle, marked out by the rue Saint-Antoine, rue des Tournelles, rue de Turenne and rue Saint-Gilles, a rectangle broken from within by the park of the royal estate. During the English occupation of Paris (1420-1436), John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, extended the district by purchasing eight and a half acres from the nuns of Sainte-Catherine for 200 livres 16 sous, thus extending the property to the fortified wall of Paris, which was then situated on what is now known as the boulevard Richard Lenoir.

This extension was annulled in 1437 after the English left. The main entrance to the hôtel was at the bottom of a cul-de-sac currently known as Impasse Guéménée. The hôtel was said to be able to accommodate 6,000 people.

Like the Hôtel Saint-Pol, the hôtel des Tournelles was a collection of buildings spread over an estate of more than 20 acres (8.1 ha), including twenty chapels, several pleasure grounds, ovens and twelve galleries including the Duke of Bedford’s famous galerie des courges (so-called due to the painted green squash or courges on its walls. Under its tiled roof the Duke’s arms, devices and heraldry were displayed). It also included a maze called ‘Dedalus’, two parks planted with trees, six kitchen gardens and a ploughed field. The council chamber was notable for the magnificence of its decoration. Three other rooms bore the names salle des Écossais (room of the Scots), salle de brique (brick room) and salle pavée (paved room).

One part of the hôtel des Tournelles, named Logis du Roi, had an entrance decorated with the French coat of arms, painted by Jean de Boulogne, known as Jean de Paris. In 1464, Louis XI built a gallery there which connected this house to the Hôtel-Neuf of Madame d’Étampes, across the rue Saint-Antoine. He also built an observatory for his doctor, Jacques Coitier. Menageries based on those at the hôtel Saint-Paul were later added to house some of the animals previously held at the hôtel Saint-Paul. New specimens were imported from Africa, such as lions, giving the enclosures the name of hôtel des lions du Roi.

No traces remain of the hôtel besides a copy of one of its gates, which forms the south gate of the église Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs, and some cellars buried below buildings in the district.

History

At the beginning of the 14th century, the building that became the Hôtel des Tournelles was merely a house facing the hôtel Saint-Pol. Pierre d’Orgemont, seigneur de Chantilly and chancellor of France and the Dauphiné under Charles VI, or perhaps his eldest son Pierre, rebuilt it in 1388. It was bequeathed to the younger Pierre in 1387. This house may have formerly been the property of Jean d’Orgemont, the presumed father of the elder Pierre.[3][4] On 19 March 1387 Pierre d’Orgemont divided his lands among his ten children, leaving the maison des Tournelles to his eldest son Pierre, bishop of Paris, who was already living there.[5] After his father’s death in 1389, the bishop sold the house on 16 May 1402 for 140,000 gold écus, to the duc de Berry, brother of Charles V. In 1404 the duc de Berry gave it to his nephew Louis, the duc d’Orléans and the younger brother of Charles VI, in exchange for the hôtel de Gixé on rue de Jouy. The duc d’Orléans was assassinated on 23 November 1407 and the hôtel passed to his heirs, becoming the property of Charles VI, who lived there from 1417 onwards. The house took the name Maison royale des Tournelles.

Thanks to the Treaty of Troyes, the English entered Paris on 18 November 1420. After Charles VI‘s death on 22 October 1422 in Paris, the hôtel was seized and became the primary residence of John of Lancaster, the Duke of Bedford, younger brother of Henry V of England and regent for the kingdom of France until his nephew Henry VI came of age. In 1436, after the English left Paris, Charles VII gave the hôtel to his Orléans cousins. When John died in 1467, the property passed to his widow, Marguerite, Duchess of Rohan. In 1486 Marguerite left the buildings to her son Charles of Orléans, father of Francis I of France. It thus became a royal residence once again. In 1563 it was still called the “hôtel des Tournelles et d’Angoulème”. It thus passed to John of Orléans, count of Angoulême, and was for a time called the hôtel d’Angoulême (not to be confused with the later Hôtel d’Angoulême Lamoignon).

Different kings of this era stayed for short or long periods at the hôtel – Louis XI made a few brief stays there:

| “ | Item, the following Thursday [1 June 1440], the Delphin [the future Louis XI] came to Paris and was lodged at the ostel [sic] des Tournelles, hard by the porte Sainct-Anthoine, and stayed only one night, not showing himself in Paris, nor his father the king coming either…[6] | ” |

Fleeing his coronation festivities,[clarification needed] the new king took refuge there on Tuesday 1 September 1461 after dinner[7] but left for Tours by 25 September.

Nor did Louis’ successors Charles VIII of France and Louis XII of France stay there much, though the latter did die there on 1 January 1515. Francis I of France did not live there, preferring the château de Fontainebleau, the Louvre and the castles on the River Loire. The Hôtel des Tournelles was used as a residence by his mother Louise of Savoy then by his mistress Anne de Pisseleu, a tradition repeated by Henry II of France when he made it the residence of Diane de Poitiers. In 1524 the magician Cornélius Agrippa lived there under the name Agrippa de Nettesheim, as doctor and astrologer to Louise de Savoie, to whom he made dead and living people appear.[citation needed]

The hôtel saw several lavish and unusual festivals, such as the “danse macabre” on 23 August 1451 before Charles, Duke of Orléans. Henry II celebrated his coronation there in 1547 and then the signing of the Treaties of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559. The last festival held there was also in 1559, to mark the double marriage of Élisabeth de France to Philip II of Spain and of the king’s sister Marguerite de France to the duke of Savoy. On this occasion, a tournament was organised on 29 June on rue Saint-Antoine, the widest street in Paris at the time and thus known as the La Grant rue St Anthoine, with the same dimensions as in the present day. During a joust in front of the hôtel de Sully (level with what is now number 62), Henry II was seriously wounded by an accidental lance thrust by Gabriel de Lorges, count of Montgomery, captain of the king’s Scottish guard. Moved to the hôtel des Tournelles, the king died there on 10 July 1559 in terrible agony, despite attempts to save him by both the famous surgeon Ambroise Paré and the surgeon to the king of Spain, Andreas Vesalius.

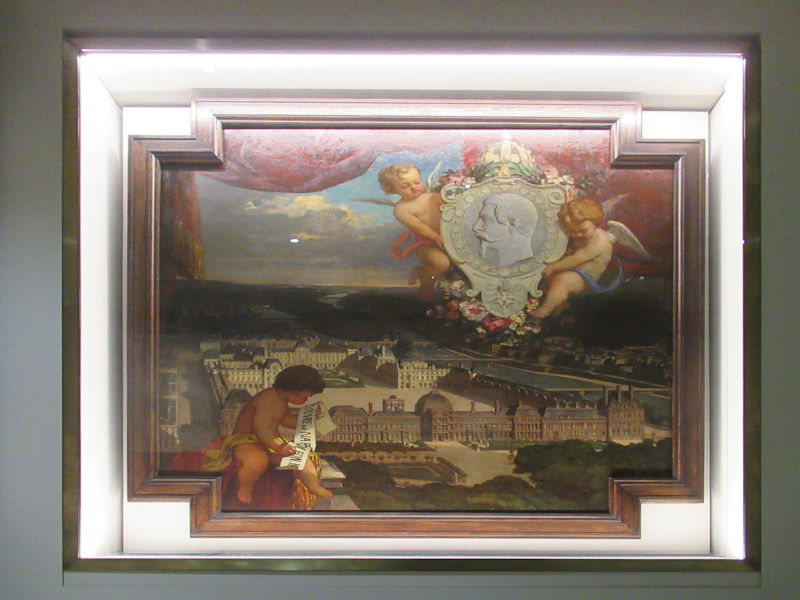

Catherine de Médici, an Italian princess who had grown up in Roman palaces, disliked the Hôtel des Tournelles’s medieval appearance and took Henry’s death as a pretext to sell it off. Gaining total power as regent to her young sons, the heirs of Henry, she turned the property into an arsenal, then had it closed and demolished. On 28 January 1563, in the name of her son Charles IX of France, she issued letters patent ordering the demolition.[8] This took place in stages and financed her major works on the more modern royal residences in Paris, particularly on the Madrid and the Tuileries. Some of the materials from the old hôtel were reused in the construction of the palace. The stables were reused to create the important Marché aux chevaux, horse market, where two thousand horses were sold every Saturday.

Certain parcels of land from the Hôtel’s estate were sold off, though a large estate remained and was used in military training. In January 1589 the estate was used to exercise the mercenaries charged with defending Paris against Henry IV of France. It also became a traditional site for bloody duels – on 27 April 1578, at 5 am, three favourites of Henry III of France beat three favourites of the duke of Guise in a duel there, with all six men ending up killed or seriously wounded.

In August 1603, Henry IV tried to re-use part of the Hôtel’s buildings to create a silk, gold and silver factory, bringing in 200 Italian artisans for this purpose, but the attempt failed. Finally, on 4 March 1604, he issued an edict instructing his minister Sully to measure out the site. He donated a parcel of 6,000 toises (yards) to his main noblemen, who built pavilions there, on the condition that they stuck to the layout, materials and main dimensions laid down by the architects Androuet du Cerceau and Claude Chastillon. On 29 March 1605 Henry wrote to Sully:

| “ | My friend, I pray you to remember what we talked of together lately, of this place where I wish that I wish to be built before the lodge which serves as a horse market for manufactures, to the end that if you have not marked out there – for renting the rest of the other places to and rent for the rest, it is doubtless that they will be unfaithful and I pray you to give me the news.[9] | ” |

Thus the place Royale, later known as the place des Vosges, was born.

References

- J-A Dulaure, Histoire de Paris, Gabriel Roux, Paris, 1853, p. 189

- Le Magasin Pittoresque, 1851, p.96

- Le journal des Sçavans, 1913, pp. 186–188

- Léon Mirot (1914). “Les d’Orgemont”. Journal des savants (in French). Berger Élie. pp. 186–188 – via Persée.

- “Partage des biens de Pierre d’Orgemont” [Sharing of the assets of Pierre d’Orgemont]. Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de Paris (in French): 130–135. 1887.

- H. Champion, Le journal d’un Bourgeois de Paris, 1881, p. 360

- Paul Murray Kendall, Louis XI, Arthème Fayard, 1974, p. 110

- Archives du royaume, section domaniale, série 9, N°1234

- Mon amy, ceste-cy sera pour vous prier de vous souvenir de ce dont nous parlasmes dernièrement ensemble, de cette place que je veux que l’on fasse devant le logis qui se fait au marché aux chevaux pour les manufactures, afin que si vous n’y avez esté vous alliez pour la faire marquer: car baillant le reste des autres places a cens et rente pour bastir, c’est sans doute qu’elles le seront incontinent et je vous prie de m’en donner les nouvelles.

Bibliography

- Jacques Hillairet, Connaissance du vieux Paris, Editions Princesse, 1956, p. 28

- F. Lazare, Dictionnaire administratif et historique des rues de Paris et de ses monuments, F. Lazare, 1844/1849, pp. 600–602

- J-A Dulaure, Histoire de Paris, Gabriel Roux, 1853, p. 189

- Gilette Ziegler, Histoire secrète de Paris, Stock, 1967, p. 69

- Le Magasin Pittoresque, 1851, pp. 95–96

- Le Magasin Pittoresque, 1907, pp. 332–334

- G. Kugelman, Les rues de Paris, Louis Lurine, 1851

- Giorgo Perrini, Paris, deux mille ans pour un joyau, Jean de Bonnot, 1992

Click Refresh to view slides

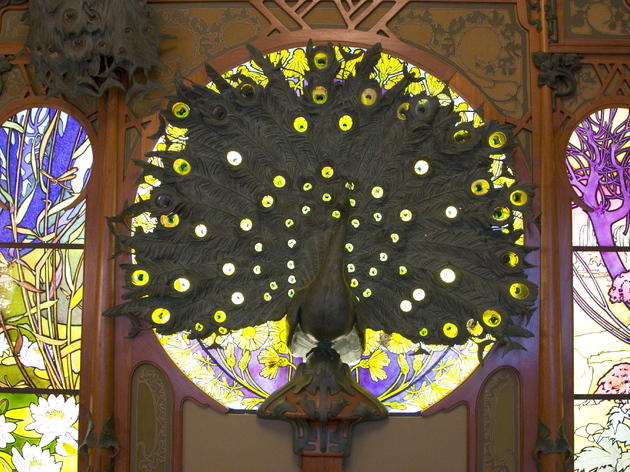

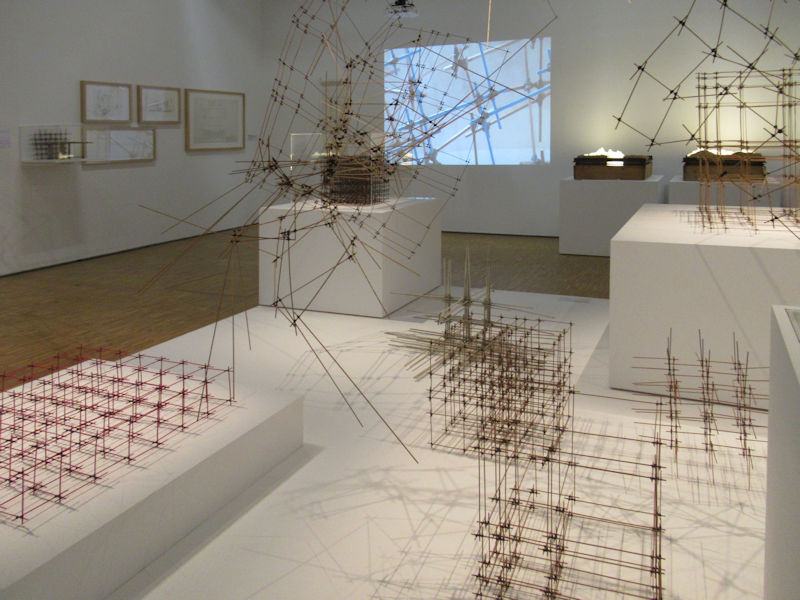

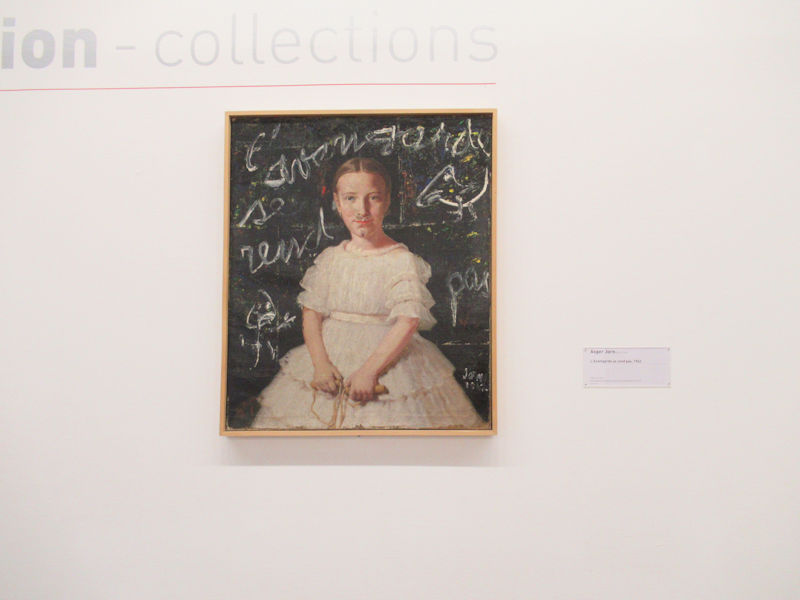

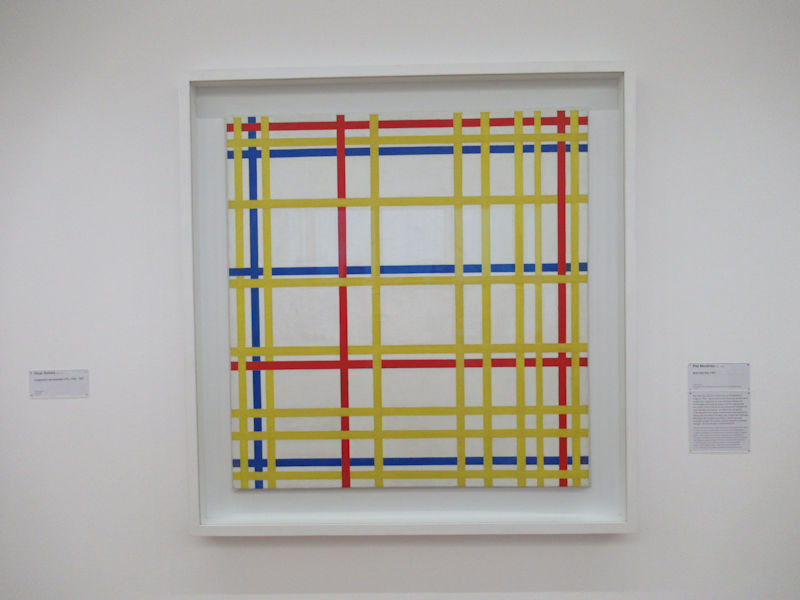

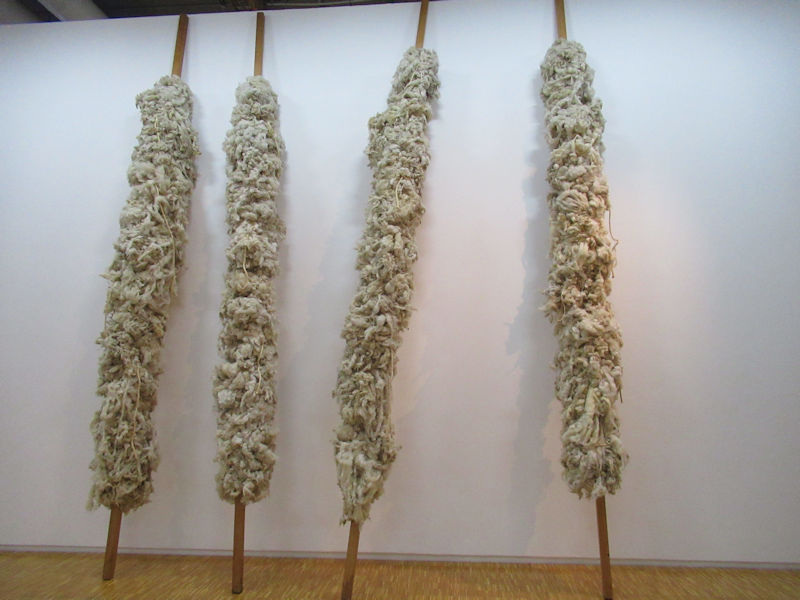

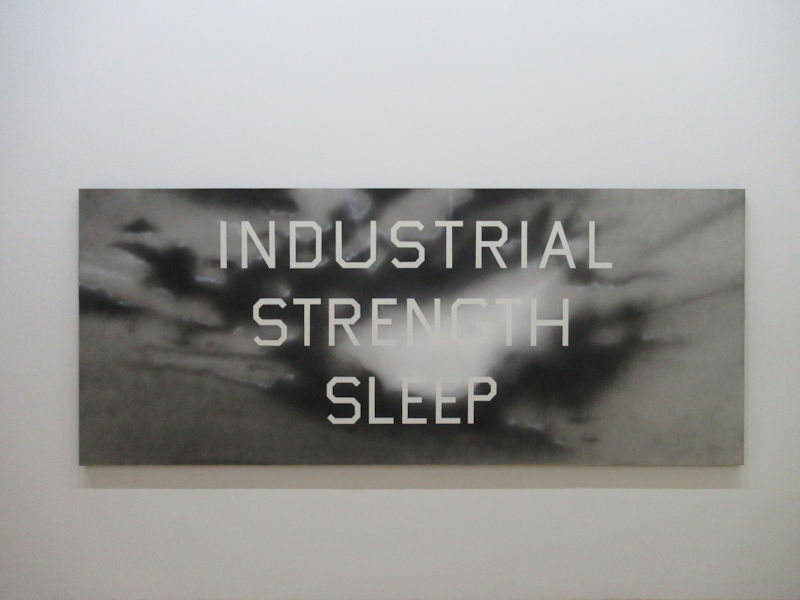

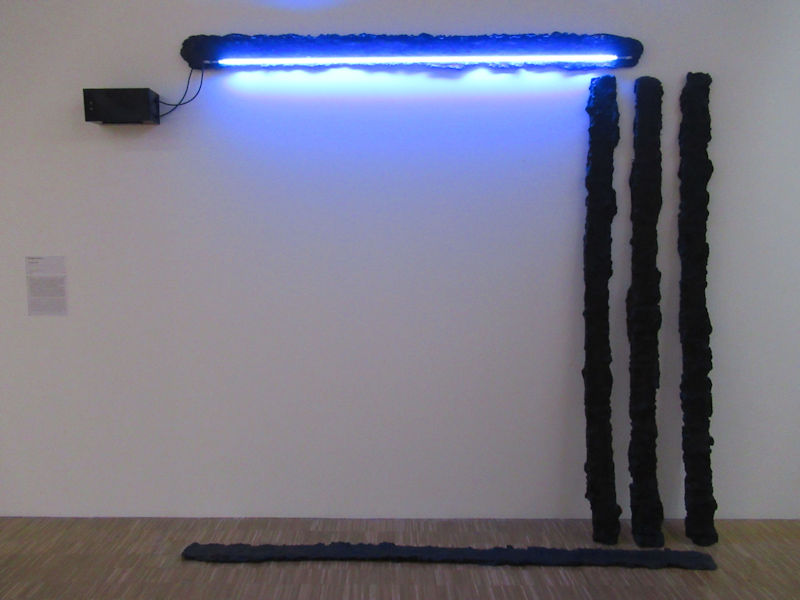

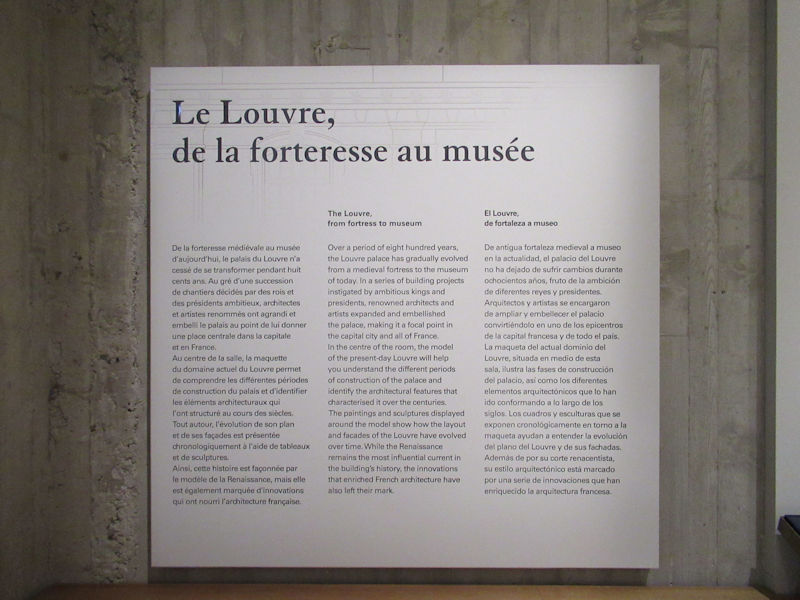

The grounds of the Jardin des Tuileries host three major Paris museums: the Musée de l’Orangerie, devoted to Monet’s Nymphéas and the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collections, the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which exhibits contemporary art and photography, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with its significant fashion and textiles collection as well as a more recent section devoted to advertising.

The grounds of the Jardin des Tuileries host three major Paris museums: the Musée de l’Orangerie, devoted to Monet’s Nymphéas and the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collections, the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which exhibits contemporary art and photography, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with its significant fashion and textiles collection as well as a more recent section devoted to advertising.