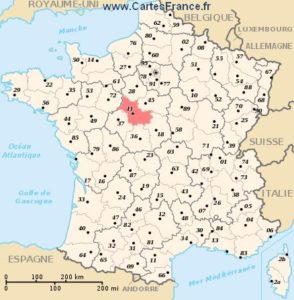

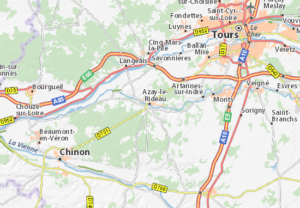

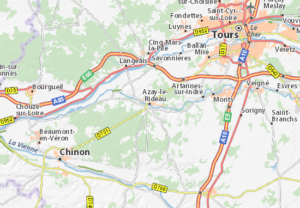

The current château of Azay-le-Rideau occupies the site of a former feudal castle. During the 12th century, the local seigneur Ridel (or Rideau) d’Azay, a knight in the service of Philip II Augustus, built a fortress here to protect the Tours to Chinon road where it crossed the river Indre. This original medieval castle fell victim to the rivalry between Burgundian and Armagnac factions during the Hundred Years’ War. In 1418, the future Charles VII passed through Azay-le-Rideau as he fled from Burgundian occupied Paris to the loyal Armagnac stronghold of Bourges. Angered by the insults of the Burgundian troops occupying the town, the dauphin ordered his own army to storm the castle. The 350 soldiers inside were all executed and the castle itself burnt to the ground. For centuries, this fate was commemorated in the town’s name of Azay-le-Brûlé (literally Azay the Burnt), which remained in use until the 18th century.

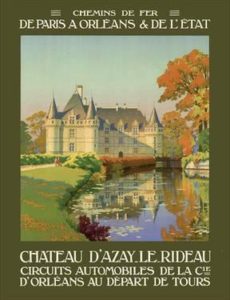

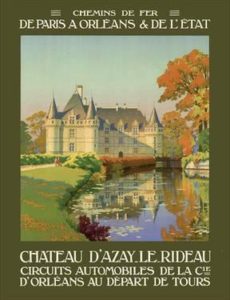

The following information and images are from the official website of Château d’Azay-le-Rideau

The Berthelots and the 16th century

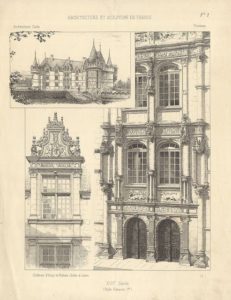

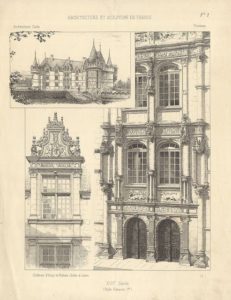

The castle remained in ruins until 1518, when the land was acquired by Gilles Berthelot, the Mayor of Tours and Treasurer-General of the King’s finances. Desiring a residence to reflect his wealth and status, Berthelot set about reconstructing the building in a way that would incorporate its medieval past alongside the latest architectural styles of the Italian renaissance. Although the château’s purpose was to be largely residential, defensive fortifications remained important symbols of prestige, and so Berthelot was keen to have them for his new castle. He justified his request to the King, Francis I, by an exaggerated description of the many ‘public thieves, foot[?] and other vagabonds, evildoers committing affray, disputes, thefts, larcenies, outrages, extortions and sundry other evils’ which threatened unfortified towns such as Azay-le-Rideau.

Gilles Berthelot had little time to enjoy his home. As with other financiers, his activities made him very rich, possibly at the expense of the crown. A general investigation ordered by Francis I revealed embezzlement.

Berthelot’s duties meant that he was frequently absent from the château, so the responsibility for supervising the building works fell to his wife, Philippa Lesbahy. These took time, since it was difficult to lay solid foundations in the damp ground of this island in the Indre, and the château had to be raised on stilts driven into the mud. Even once the foundations were laid, construction still progressed slowly, as much of the stone for the château came from the Saint-Aignan quarry, which was famous for its hard-wearing rock but was also around 100 km (62 mi) away, meaning that the heavy blocks had to be transported to Azay-le-Rideau by boat.

The château was still incomplete in 1527, when the execution of Jacques de Beaune, (the chief minister in charge of royal finances and cousin to Berthelot) forced Gilles to flee the country. Possibly fearing the exposure of his own financial misdemeanours, he went into exile first in Metz in Lorraine, and later in Cambrai, where he died just two years later. Disregarding the pleas of Berthelot’s wife Philippa, Francis I confiscated the unfinished château and, in 1535, gave it to Antoine Raffin, one of his knights-at-arms. Raffin undertook only minor renovations in the château, and so the building works remained incomplete, with only the south and west wings of the planned quadrilateral ever being built. Thus, the château preserved the distinctive, but accidental, L-shape which it retains to this day.

17th–18th centuries

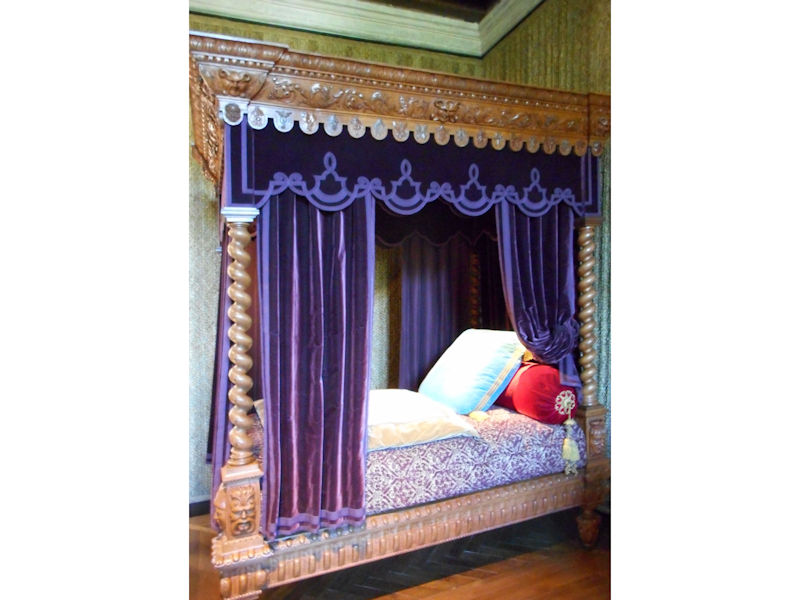

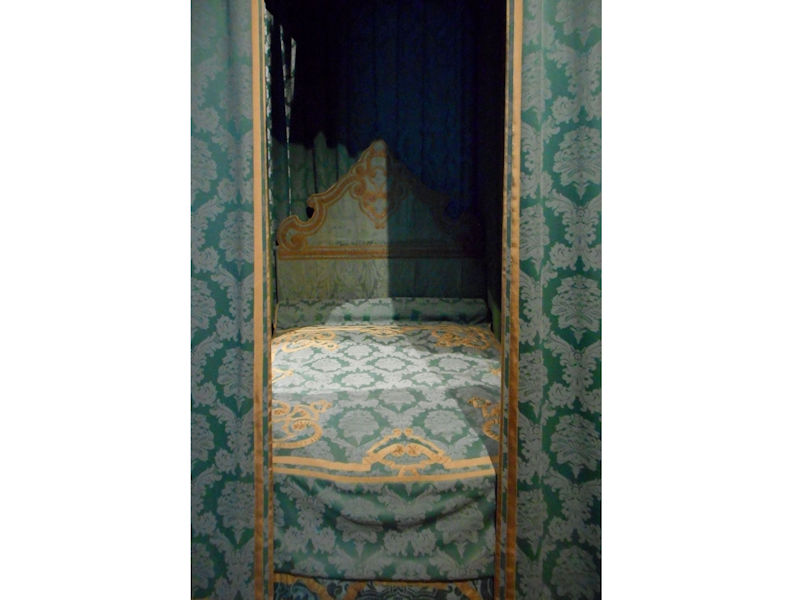

In 1583, Raffin’s granddaughter Antoinette, a former lady-in-waiting to Margaret of Valois, took up residence in the château and, with the help of her husband Guy de Saint-Gelais, began modernising the décor. Azay-le-Rideau was then inherited by their son Arthur and his wife Françoise de Souvre, a future governess to Louis XIV, and it was during their ownership that the new château received its first royal visit: on June 27, 1619, while on his way from Paris to visit his mother, Marie de Medici, in Blois, Louis XIII broke his journey to spend the night in Azay-le-Rideau. Later in the century, his son Louis XIV would also be a guest in the same room.

The Biencourts and the 19th century

Biencourt dining room

The Raffins and their relations by marriage the Vassés retained ownership of the château until 1787, when it was sold for 300,000 livres to the Marquis Charles de Biencourt, field marshal of the king’s armies. The château was in poor condition, though, and from the 1820s, Biencourt undertook extensive alteration work. In 1824, he added a ‘Chinese room’ (destroyed in the 1860s) to the ground floor in the south wing, and in 1825 or 1826 decorated the library with carved wood panelling to match the drawing room on the opposite side.

It was his son, Armand-François-Marie, a guard of Louis XVI who participated in the defence of the Tuileries on 10 August 1792, who began the first extensive restoration of the château. This included restoring the old medallions and royal insignia on the staircase (which had been covered up during the Revolution), extending the courtyard façade and adding a new tower at the east corner. These developments destroyed the last vestiges of the old medieval fortress and meant that the château at last achieved a finished appearance. For these renovations, he employed the Swiss architect Pierre-Charles Dusillon, who was also working on the neighbouring château of Ussé.

During the Franco-Prussian War, the château was once again threatened with destruction. It served as the headquarters for the Prussian troops in the area, but when one night a chandelier fell from the ceiling onto the table where their leader, Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia, was dining, he suspected an assassination attempt and ordered his soldiers to set fire to the building. Only his officers’ assurances that the lamp had dropped by accident persuaded him to stay his hand and thus saved the château from a second burning.

Original wood engraving by Pannemaker, 1877

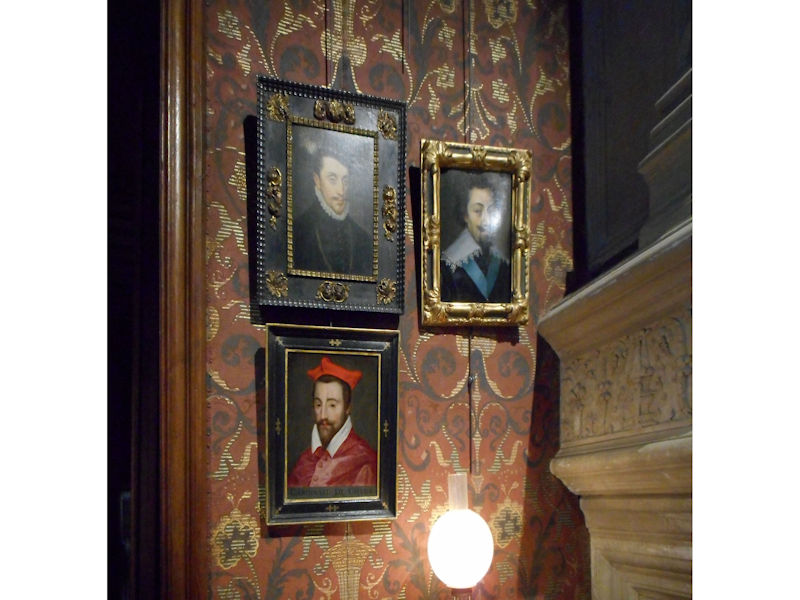

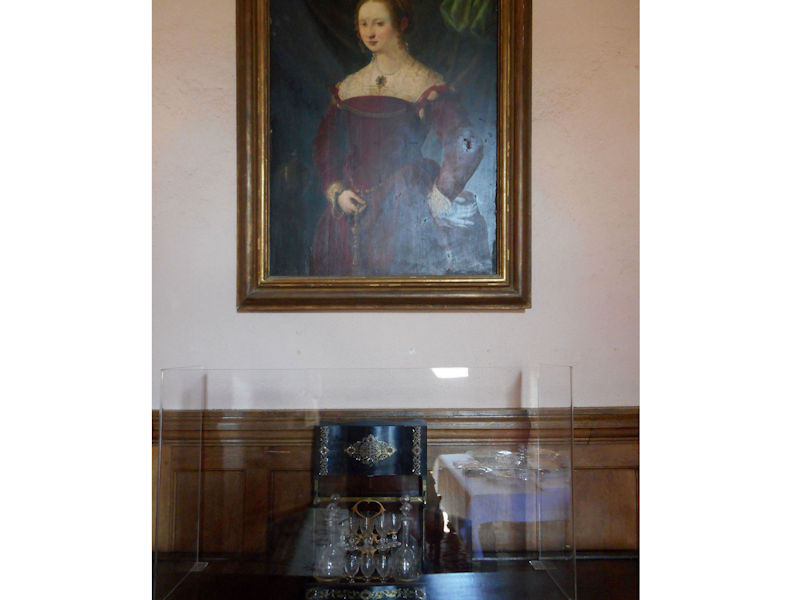

Following the Prussian troops’ retreat, Azay-le-Rideau returned to the Biencourts. In this period, the château became well known for the collection of more than 300 historical portraits which the owners displayed there and which, unusually for a private collection, could be visited by the public. In 1899, financial difficulties forced the young widower Charles-Marie-Christian de Biencourt to sell the château, along with its furniture and 540 hectares of land, to the businessman Achille Arteau, a former lawyer from Tours who wanted to sell its contents for profit. As a result, the château was emptied and its artwork and furniture dispersed.

The Château in the 20th century

In 1905, the estate was purchased by the French state for 250,000 francs and became a listed Historical Monument. During the early years of the Second World War, 1939-1940, the château provided a home for the Education Ministry when they, like many other French ministries, withdrew from Paris. The château d’Azay-le-Rideau is now one of many national monuments under the protection of the Centre des monuments nationaux, and also forms part of the Loire valley UNESCO World Heritage Site.

A major restoration project (2014 – June 2017)

Restoration began in the park and focused on the renewal and maintenance of its arboreal heritage in the spirit of a 19th century landscaped park: soil regeneration, restoration of alleys and bridges, upgrading of electrical equipment to standards and new lighting of the park, restoration of masonry works and implementation of an irrigation network supplied by river water.

Refurnishing of the Biencourt Salon

The Centre des Monuments Nationaux chose to restore the ground floor of the Château d’Azay-le-Rideau to all the luxury and comfort of its previous owners, the Biencourt family, who, between 1791 and 1899, paid utmost attention to the furniture and furnishings of the château. Restoration work has completed the reconstruction of the Château of Azay as it was the 19th century when it was admired by travellers and, in particular, by Prosper Mérimée and Honoré de Balzac.

The Biencourt Salon before refurnishing

The Biencourt Salon after refurnishing

Restoration of the roofing and façades

The restoration project, lasting a total of 34 months, also focused on the roof structures – the overall roofing, the upper parts of the masonry, sculptures and woodwork. Because of the amount installations and scaffolding, the restoration of façades and roofing were scheduled at the same time. Installation of the scaffolding, part of which is in water, was a complex issue. An umbrella covering the entire site enabled the carpenters, roofers and stonemasons to work safely providing protection of the roof spaces and floors during the procedure.

Restoration of the court stairwell detail.

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

Wikipedia

View of the château by Roger de Gaignières, 1705. Paris, French National Library, d’Estampes section.

View of the château by Roger de Gaignières, 1705. Paris, French National Library, d’Estampes section.

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.