The Château’s Surroundings in the 16th Century

The following content was retrieved in its entirety from https://www.chambord.org/fr/histoire/ 10/11/2017.

Francis I’s primary concern when Chambord was constructed was taming the Cosson, the river that crosses the estate from east to west. The Cosson’s meandering waters created a hostile, marshy environment around the château that “in no way echoed the magnificence of the château” (Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, 1576).  The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo

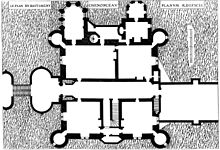

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

The Major Projects of the 17th Century

It was not until the reign of Louis XIV that major projects were undertaken to landscape the areas around the château.

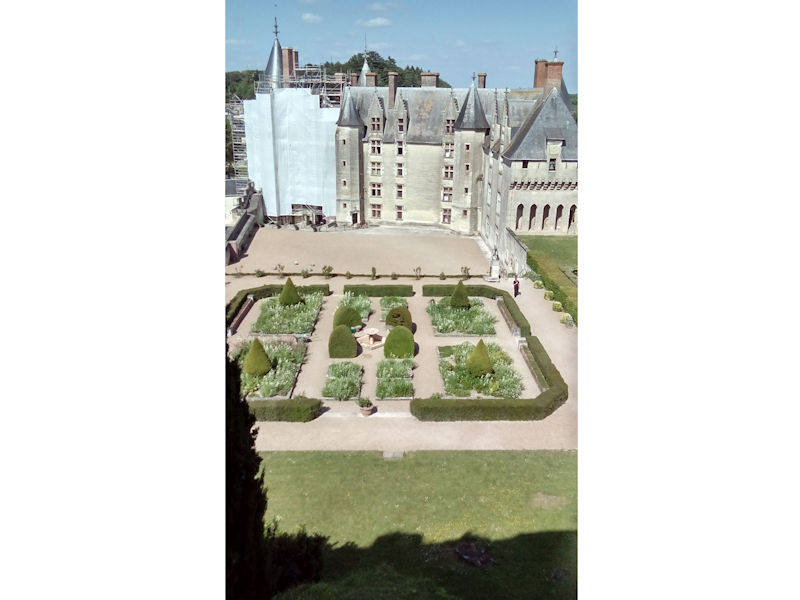

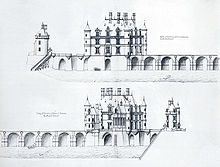

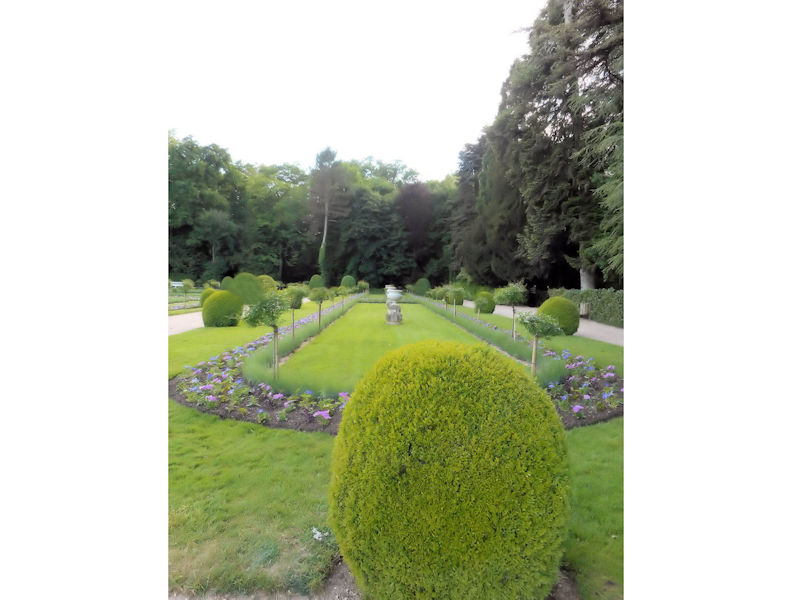

The Sun King ordered the planting of French formal gardens in front of the building’s grand facade. Two projects were proposed to the king by Jules Hardouin-Mansart and his agency. One presented a half-hexagon-shaped area on the northeast side of the château and stables planted with three triangular gardens and bordered by the canalized Cosson river on one side. The château was surrounded by wide moats. In front, the parterre continued with two flowerbeds and the Cosson river canalized into the shape of a half moon. The second project, though quite similar, presented a less geometric canal design. The path of the Cosson was regulated but it followed the curves of its original course. The parterres occupied the same north and east spaces but over less area (they no longer occupied the area behind the stables). Their shape also differed slightly, particularly to the north where their structure appeared trapezoidal. It was the second project that was partially implemented, as shown by the geophysical surveys carried out in 2014.

The first phase of the projects, starting around 1684, consisted of banking up the earth around the monument to raise it to a level that would flood less, or not at all. Retaining walls were then built to encircle this artificial terrace, first on the moat side of the château and then at the west and southeast ends. Finally, the canalization of the Cosson was undertaken to follow the contours of the parterre.

The current structure of the space gradually took shape. However, work was quickly halted.

Completion of the Parterre in the 18th Century

Work started again whilst Stanislas Leszczynski, King of Poland, was at Chambord (1725–1733). He alerted the Bâtiments du Roi, the department responsible for building works for the royal estate, to the nuisance caused by the continued presence of the swamps surrounding the château (especially the malaria epidemics that spread through his retinue during the summertime). Starting in 1730, La Hitte, the controller of the Bâtiments du Roi assigned to Chambord, coordinated the continuation of the work initiated under the reign of Louis XIV: the installation of bridges (including the bridge that links the parterre to the château) and dykes, the raising of the walls of the artificial terrace and the depositing of additional soil on the terrace to make it level with the walls, and the cleaning and widening of the Cosson to create a canal.

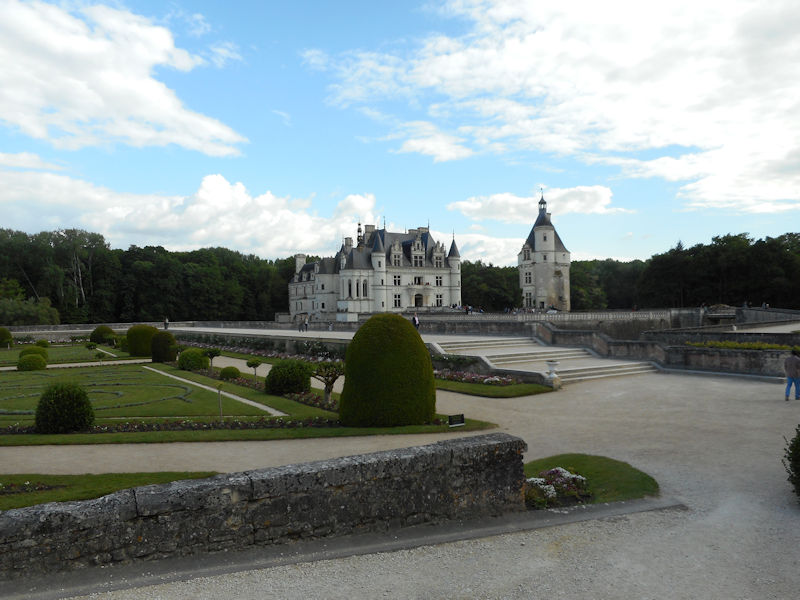

A garden “in the French style” was then planted over 6.5 hectares, according to a drawing completed in 1734. A gardener was hired to continue planting and to maintain it: Jean-Baptiste Pattard, who had been formerly employed on the terracing of the parterre.

Starting in 1745, the château and its estate were made available to the Marshal General of France, Maurice de Saxe, by King Louis XV. He occasionally visited Chambord between 1746 and 1748, then stayed there continuously until his death [at the château] in 1750. Improvements to the garden continued during this period thanks to the further planting of boxwood trees, chestnut trees, and hornbeam bowers, in addition to the installation of plants and trees in containers along the garden’s pathways (250 pineapple trees, 121 orange trees, 1 lemon tree, and 1 lime tree were mentioned in the 1751 inventory).

A portion of the parterre was redesigned several years later when the estate was made available to the kingdom’s stud farm. The two beds of east lawn were divided lengthwise to create four squares, with a well used to mark the center of the composition.

The Steady Disappearance of the Garden

Once the Revolution started, the garden suffered from a lack of maintenance. In 1817, a condition report of the Chambord estate showed that the trees and shrubs were no longer “trimmed,” the pathways were overgrown with weeds, and the flowerbeds, which had once been full of flowers, were planted with fruit trees or left uncultivated. As for the château’s moats, they had dried up and been partially turned into a vegetable garden!

Between the 19th century and 1930, the Chambord estate became the property of Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, the grandson of Charles X, then his nephews, the princes of Bourbon-Parma. During this period, the garden was kept according to a simplified structure: all that remained were the beds of lawn, the sand-covered pathways, and the rows or copses of trees that required little maintenance. A complete replanting project was entrusted to the famous landscape architect Achille Duchêne but was never carried out.

Finally, the last known landscaping step: the parterre was divided into large rectangles of meadow in the 20th century. A row of tall trees remained to the west and certain pathways were marked with yew topiary, shrubs, and rose bushes in front of the château’s facade.

In 1970, all of it was taken out, keeping only the lawn. Two years later, the moats were refilled. This “transitional” landscaping lasted until the 18th-century French formal garden replanting project, which was started in 2016.

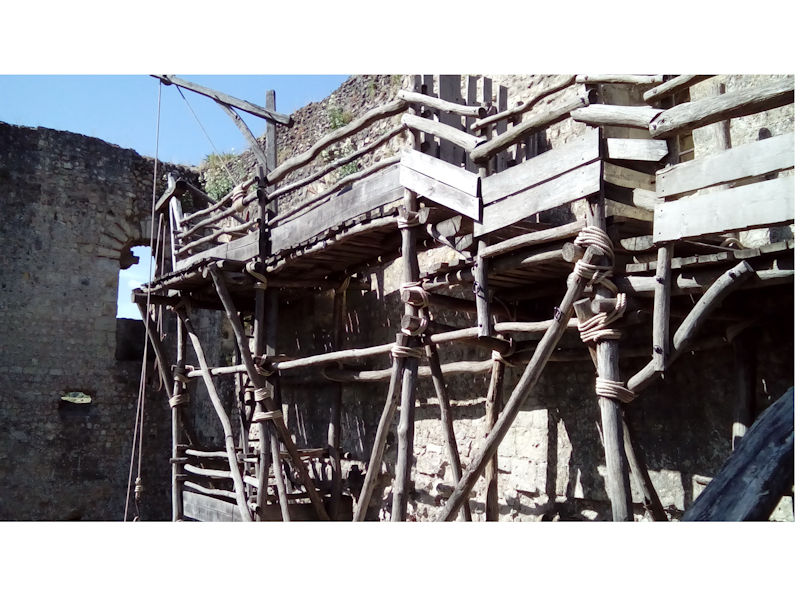

THE WORK SITE

The project was implemented by Jean d’Haussonville, general manager of the National Estate of Chambord (since 2010). During the course of the project, no less than one hundred people were involved.

The National Estate of Chambord, which carried out this project, was represented by Pascal Thévard, director of buildings and gardens.

The SARL [Limited Liability Company] Philippe Chauveau was the OPC (Scheduling, Management and Coordination) Coordinator. Philippe Chauveau acts as primary contractor in the department of Loir-et-Cher, the region of Orléans and Tours. It specializes in industrial construction and the restoration of factories, commercial buildings and local authorities, historic renovation and restoration, as well as in the construction of custom-designed homes.

The SPS (Health & Safety) Coordination is provided by AB Coordination, whose company boasts many experts in construction site safety and security.

Philippe Villeneuve, head architect of historic monuments, was assisted by landscapist Thierry Jourd’heuil.

Further viewing:

Chambord : les inondations vue du ciel

L’Enigme des Rois de France, de Chambord à Versailles.

Chambord : le château, le roi et l’architecte

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

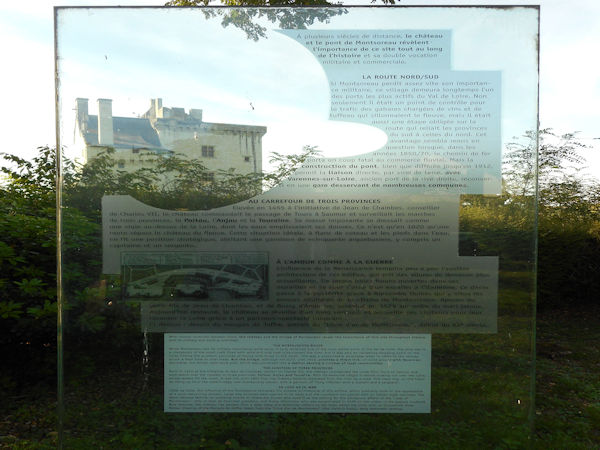

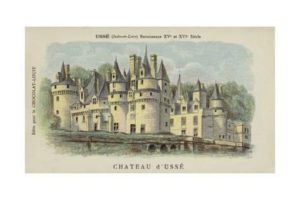

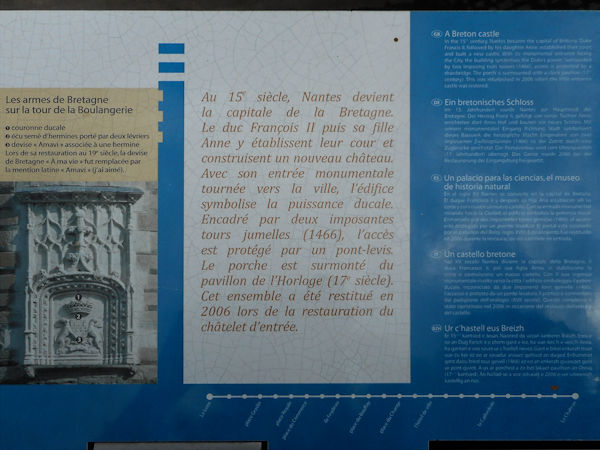

Under the Plantagenet kings, the château was fortified and expanded by Richard I of England (King Richard the Lionheart). However, King Philippe II of France recaptured the château in 1206. Eventually though, during the Hundred Years’ War, the English destroyed it. The château was rebuilt about 1465 during the reign of King Louis XI. The great hall of the château was the scene of the marriage of Anne of Brittany to King Charles VIII on December 6, 1491 that made the permanent union of Brittany and France.

Under the Plantagenet kings, the château was fortified and expanded by Richard I of England (King Richard the Lionheart). However, King Philippe II of France recaptured the château in 1206. Eventually though, during the Hundred Years’ War, the English destroyed it. The château was rebuilt about 1465 during the reign of King Louis XI. The great hall of the château was the scene of the marriage of Anne of Brittany to King Charles VIII on December 6, 1491 that made the permanent union of Brittany and France.