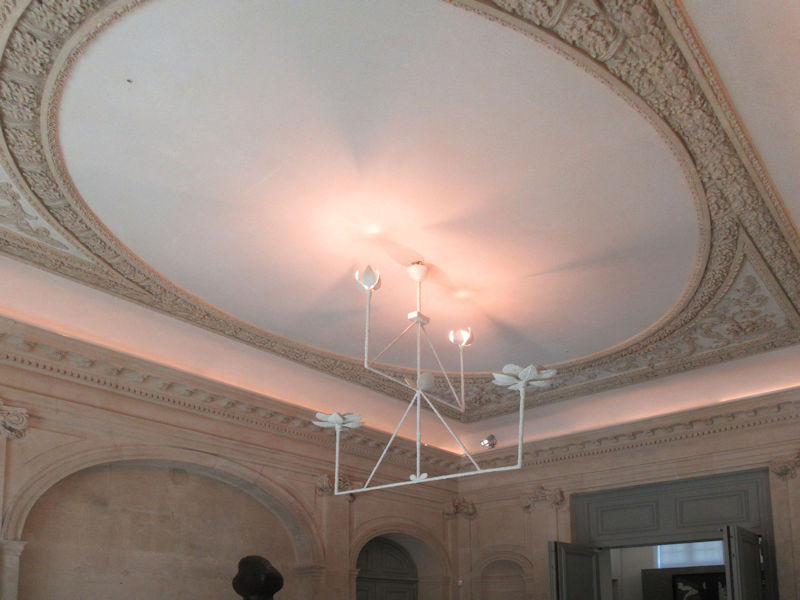

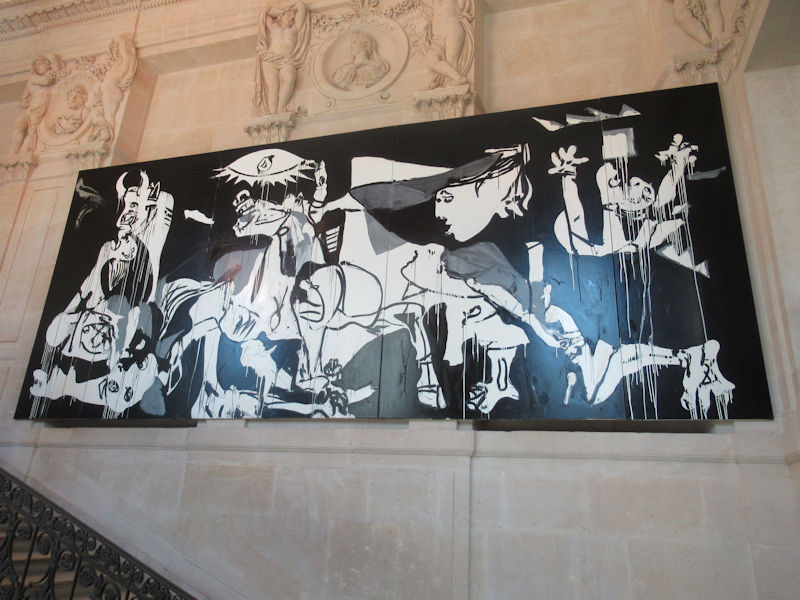

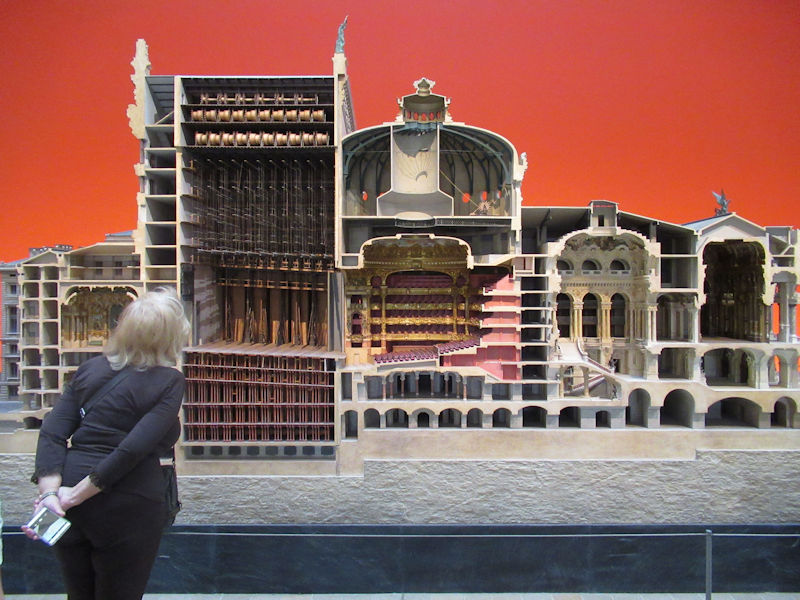

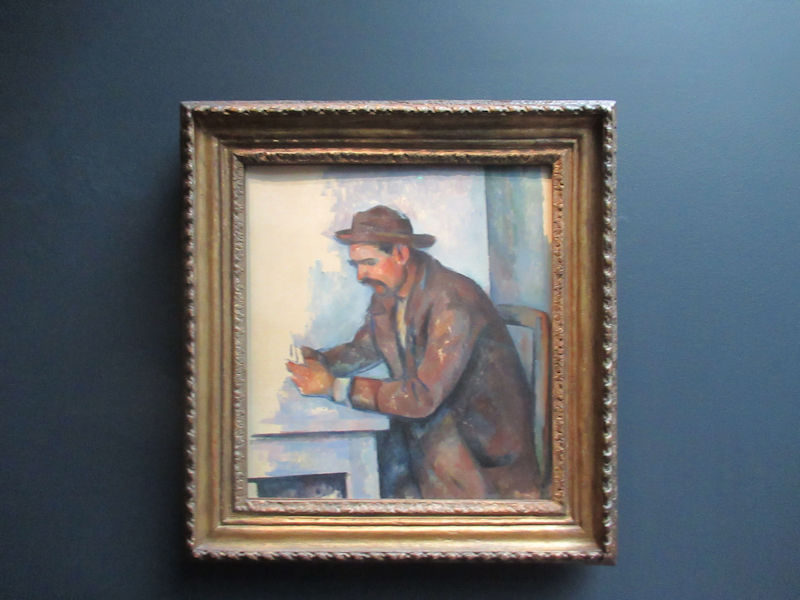

Central staircase.

HISTORY – Translated from Musée Picasso website

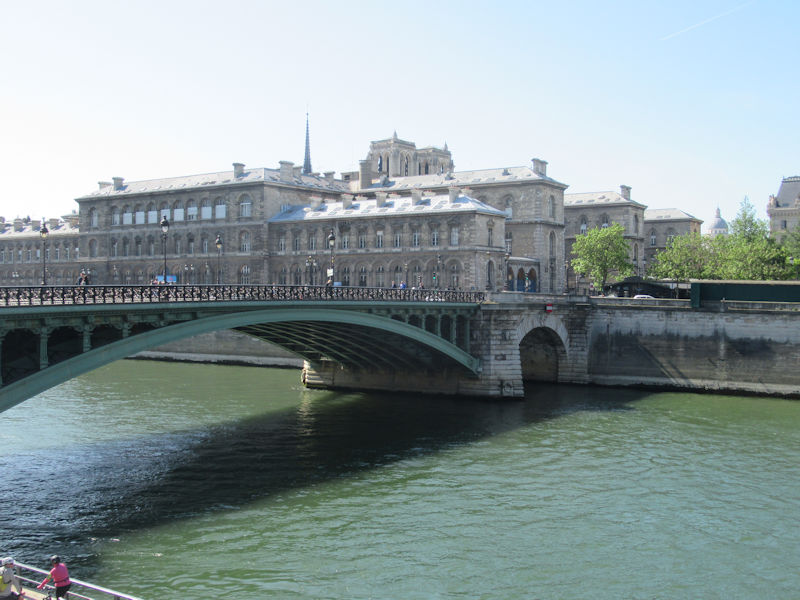

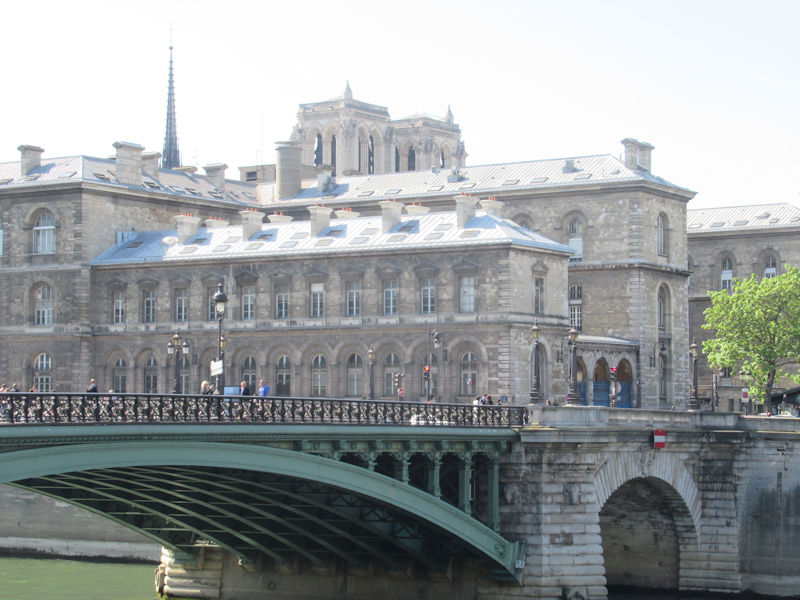

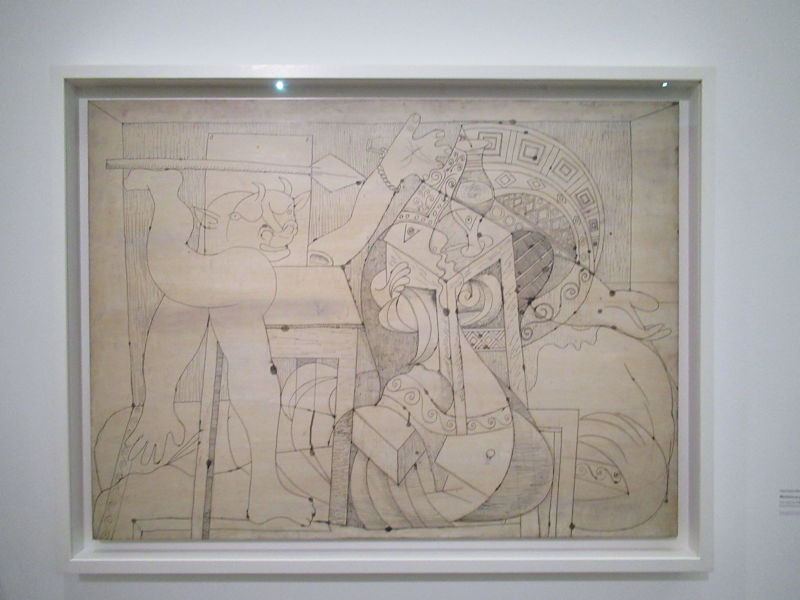

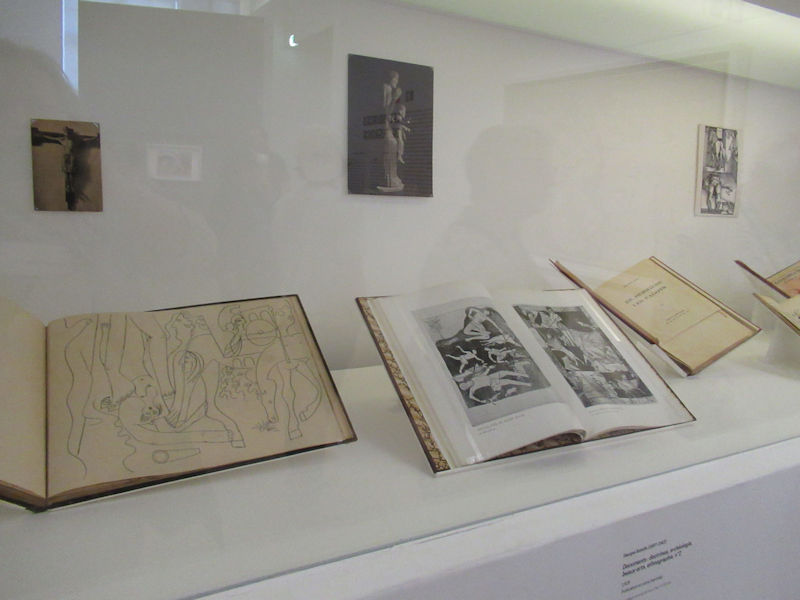

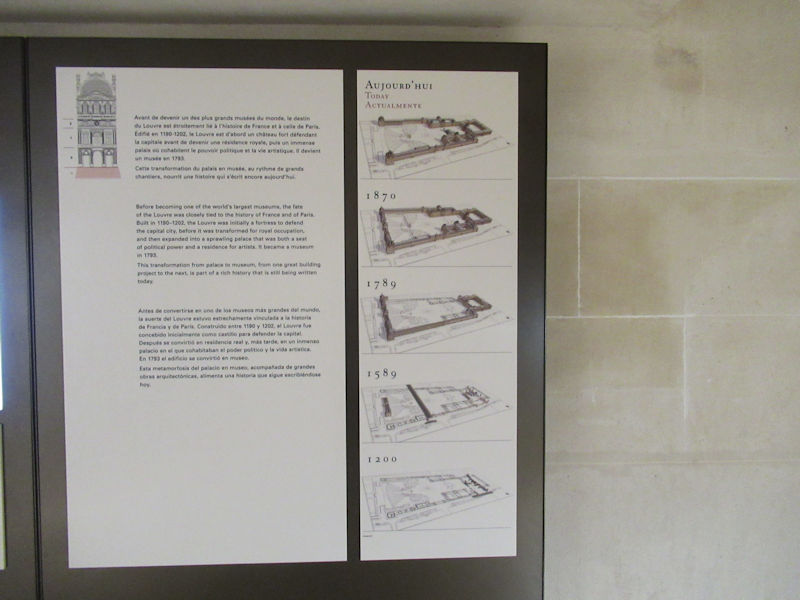

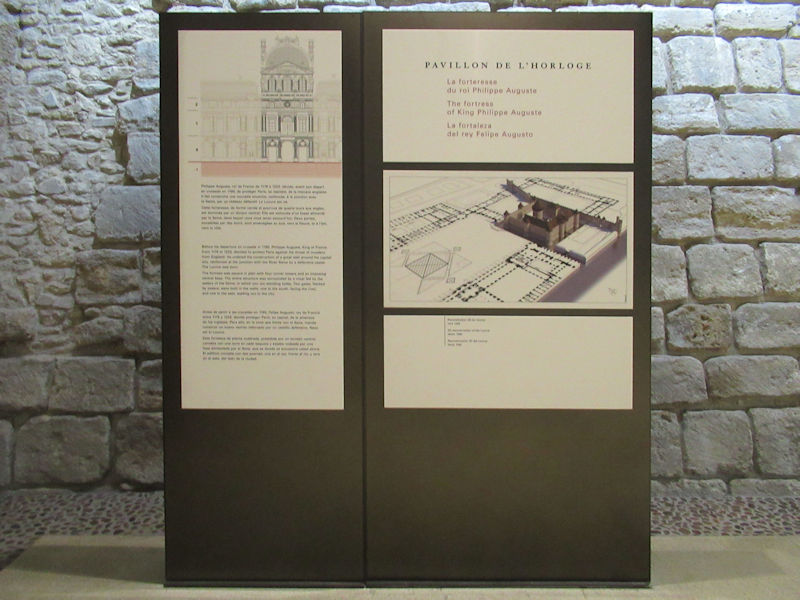

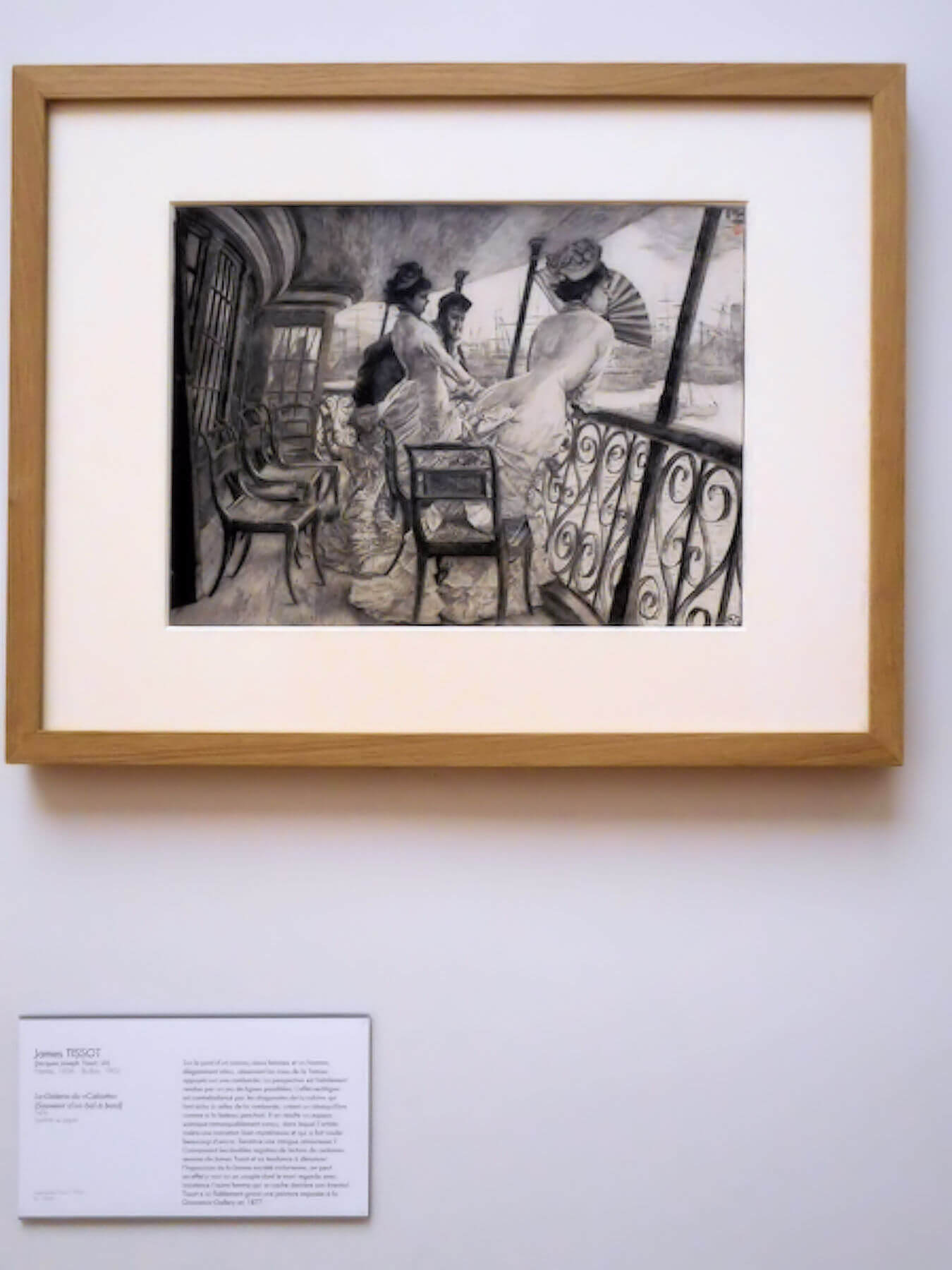

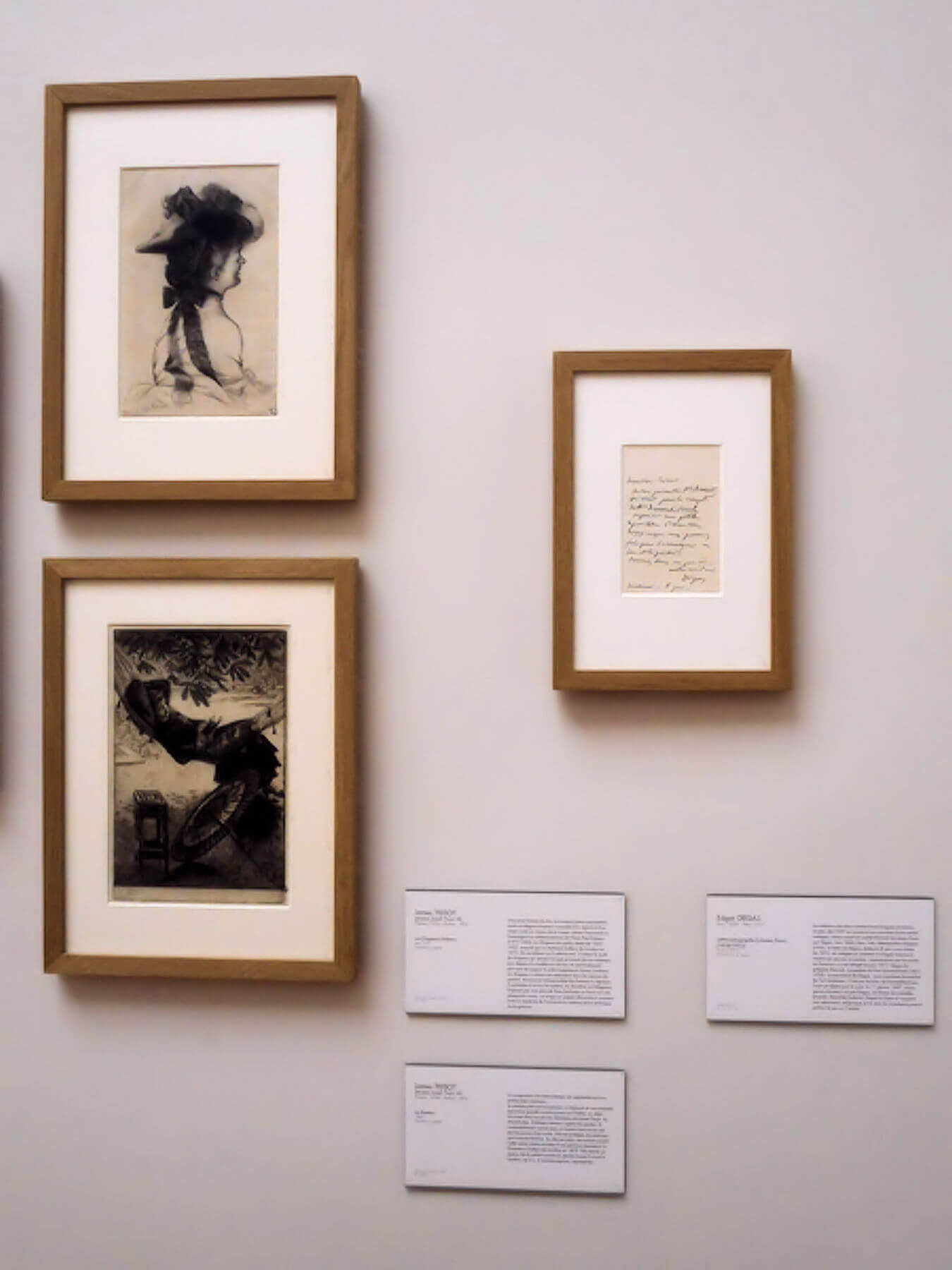

The decision to install the “dation Picasso” (works donated in lieu of estate taxes) in the Hôtel Salé was made very quickly, in 1974, just one year following the artist’s death. But in some way the fate of Pablo Picasso’s estate had been pre-planned, in particular by the “acceptance in lieu” mechanism introduced in the late 1960s, made urgent by the artist’s advancing years. With this process, which gave the State permission to acquire the bulk of Picasso’s works, enriched by donations from his heirs, it was important to find a place to preserve and exhibit them. Supported by the artist’s family, Michel Guy, French Secretary of State for Culture, chose the Hôtel Salé, a private mansion at 5 rue de Thorigny in Paris’ 3rd arrondissement, to house Picasso’s collection. Owned by the City of Paris, the building had been awarded the Historic Monument status on 29 October 1968.

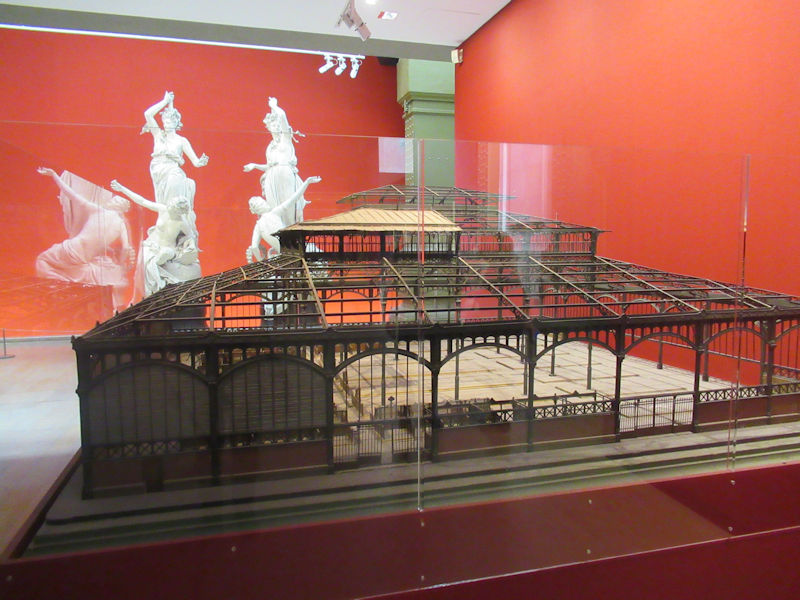

The Historic Monuments department commenced the restoration programme in 1974. In March 1975, after deliberation, Paris City Council confirmed that the Hôtel Salé would indeed house the Musée National Picasso, a natural choice given that the artist’s work was produced within the walls of large private mansions and other historic buildings, such as the châteaux of Boisgeloup and Antibes and Villa La Californie. The intention was also to create an architectural contrast between the nascent Centre Pompidou, whose foundations were just being laid, and the monographic heritage site the old Hôtel Salé was transforming into, a nearby showcase for 20th century art and a depository for Pablo Picasso’s estate. Picasso’s art was to shine in the multiple exhibition areas dedicated to 20th century art divided between highly-contemporary architecture and patrimonial spaces. A lease of 99 years was agreed in 1981, the City of Paris renting the Hôtel Salé from the State for a token sum provided it carried out the renovation and took care of the building’s upkeep.

The property was renovated and refurbished between 1979 and 1985 by the architect Roland Simounet to become a dedicated place to preserve and display art. Following a public design competition that put four architects in the running (Roland Simounet, Carlos Scarpa, Jean Monge and Roland Castro’s GAU Group), Roland Simounet was awarded the contract to install the Musée National Picasso within the Hôtel Salé. A well-recognised and experienced architect, Roland Simounet was born in 1927 in Algeria where he worked until 1964 after a period studying at the École d’architecture du Quai Malaquais in Paris. He worked on temporary settlements, carrying out a study for the shanty town in Algiers on behalf of the International Congress for Modern Architecture in 1953, and building the Djenan el Hassan housing project in 1957. His experience combined the modernist architecture of Le Corbusier with Mediterranean tradition—which had already inspired him, and he became interested in horizontality. The LaM, a modern art museum in Villeneuve d’Ascq (1983), for which he won the public competition in 1973, is a good representation of his approach to arranging architectural blocks in an organised sequence, a model also found in the Museum of Prehistory in Nemours (1981), with its asymmetrical footprint comprising different wings, adapted to the uneven terrain.

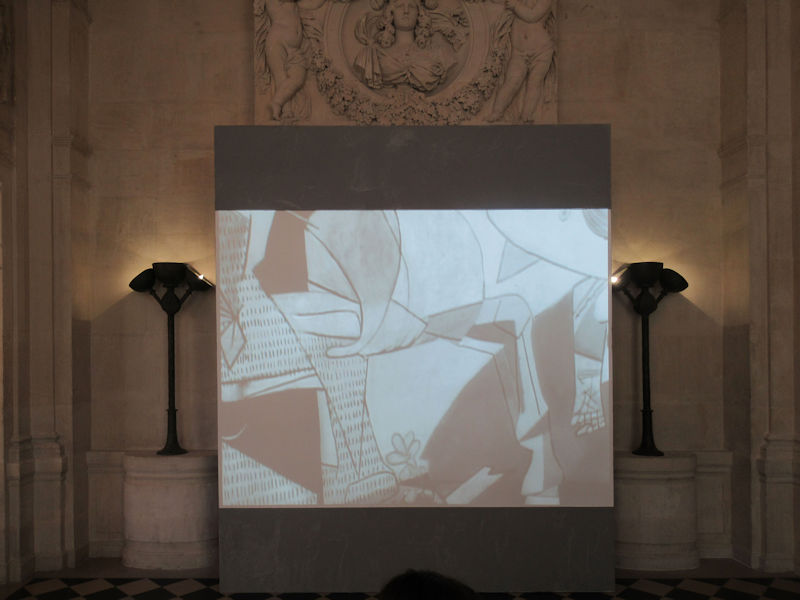

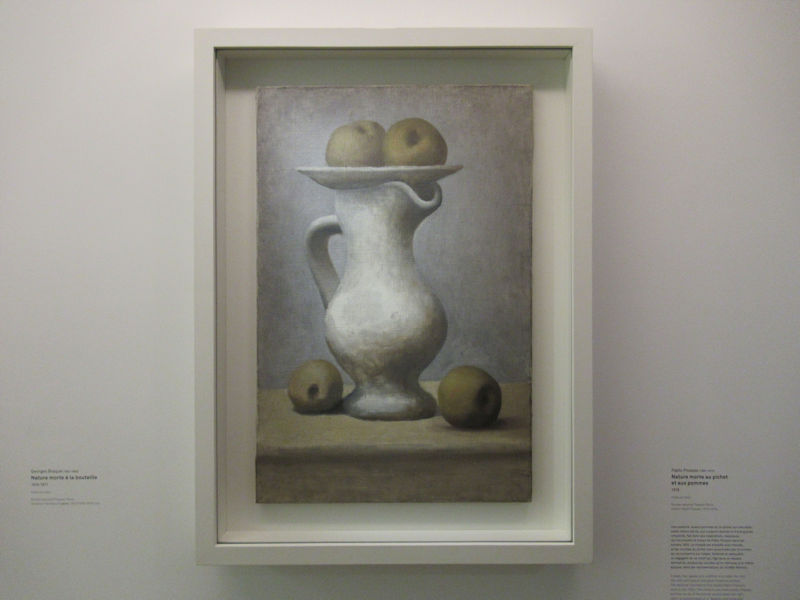

The Hôtel Salé presented a particular challenge. The project consisted of appropriating the space inside an existing building and respecting the listed parts of the property with its superb stucco and stone décor as seen in the hallway, central staircase, and Salon de Jupiter. Simounet confronted these constraints just like he had done with the bumps in the ground in Nemours: his proposal was the only one submitted to the competition to fit the museum within the confines of the building without the need to extend the property. The modernist box designed by Roland Simounet was superimposed within the monument in a dialectical style as subtle as it was complex, in every dimension.

The central staircase, which leads “naturally” to the first floor, was a pivotal component of the project. The exhibition route flowed like a sinusoid carved with nooks and crevices. A ramp provided an alternative means of moving from floor to floor. The gloss paint contrasted with the matt paint to make the walls flow. This work differed from the renovation of the Abbey of Saint-Germain des Prés, for which the interior was structured like a shell inside the building. In the Hôtel Salé, the building retained its spaciousness and its external and internal visibility. Through the variety of ambiences established in each part of the building and the transparency between the original building and exhibition spaces, the museum offered an architectural promenade introducing visitors to a grand 17th-century house at the same time as Picasso’s work. The furnishings were designed by Diego Giacometti.

However, due to technical problems, budget cuts and a slew of planning changes, the completed renovation was in many respects different from the initial design supported by Roland Simounet. The ramps and mezzanines had to be reduced. Certain spaces were abandoned, such as the temporary exhibition spaces, originally planned to take up the outbuildings, and the multimedia room for which the outbuildings’ basement was initially designated. The plan to create a building for artist studios and services running along the gardens, on the side of rue du Vieille du Temple, was also rejected, the area instead converted into a large technical facility. These lost spaces made it impossible to display the full magnitude of the collection.

The Musée National Picasso was inaugurated in October 1985.

Roland Simounet was awarded the Silver T-Square architecture prize for his work on the Hôtel Salé.

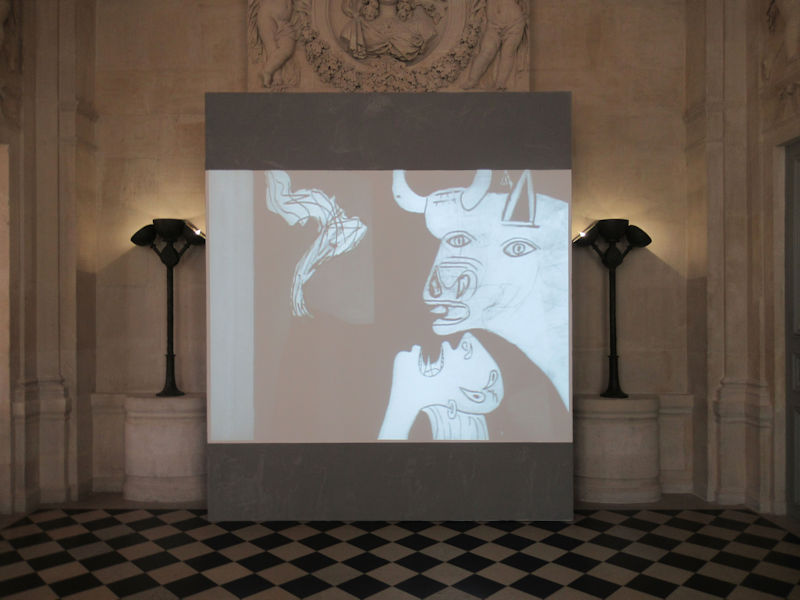

INA archives

In partnership with the INA, France’s national audiovisual institute, here is a selection of videos regarding the opening of the museum.

1975 : TF1, 1 pm news programme, 21 January 1975: the Musée Picasso installed in the Hôtel Salé in Paris’ Marais district. To commemorate its renovation, the programme broadcast the long and rich history of this remarkable building. (in French)

1979 : Antenne 2, Zig Zag, 12 December 1979: Maurice Aicardi, President of the Interministerial Commission for the Preservation of National Artistic Heritage, explained the circumstances surrounding the Pablo Picasso “dation” and more generally the principles underlying the law of 31 December 1968 regarding the acceptance in lieu mechanism. Presented from the main staircase at the Hôtel Salé, during its renovation. (in French)

1984 : TF1, the 1 pm news programme, 5 July 1984:the architect Roland Simounet presents, on the site of the Musée Picasso, the main components of the Hôtel Salé’s renovation, illustrated by the technical innovations shown during the course of the news item. (in French)

1985 : Antenne, 2. Midi 2, 23 September 1985: for the occasion of the inauguration of the Musée Picasso, a report on transferring Pablo Picasso’s works from the Palais de Tokyo’s storerooms to the picture rails in the Hôtel Salé. The first images of the works being hung are explained by Dominique Bozo, chief curator at the Musée Picasso. (in French)

The Hôtel Salé

The Hôtel Salé is probably, as Bruno Foucart wrote in 1985, “the grandest, most extraordinary, if not the most extravagant, of the grand Parisian houses of the 17th century”. The building has seen many occupants come and go over the centuries. However, paradoxically, before the place was entrusted to the museum, it was rarely “inhabited”, but instead leased out to various private individuals, prestigious hosts and institutions.

It was built by salt-tax farmer, Pierre Aubert, around the same time as another ambitious construction was realised—Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte by Nicolas Fouquet. Indeed, Pierre Aubert was a protégé of Fouquet. Aubert made his fortune in the 1630s-1640s by various schemes, including an advantageous marriage and the purchase of successive appointments, eventually becoming an important financier on the Parisian market and advisor and secretary to the King. Joining the salt tax offices, Pierre Aubert collecting taxes on salt as a lump sum in the name of the king, consolidated his standing. His position created a name for the house, which quickly became known as the Hôtel Salé (“salé” meaning “salty” in French).

The future owner of Hôtel Salé was therefore a “middle-class gentleman” seeking to assert his recent social advancement. As a site, he chose an area still underdeveloped, and where Henry IV of France wished to encourage construction with the building of the Place Royale. This urban extension of the old Marais (“marsh” in French) bordered the Hôpital Saint-Gervais and its “fields” (cultures) corrupted to “habits” (coutures) worn by the Saint Anastasia nuns. Pierre Aubert, Lord of Fontenay, purchased land covering 3,700 square metres, in the north of Rue de la Perle, for 40 000 pounds from this Order. To design the building, he chose the young unknown architect Jean Boullier de Bourges (or Jean de Boullier), of whom we know little today. He belonged to a local family of stonemasons and his grandfather had already served Pierre de Fontenay’s in-laws, the Chastelain family. Three years later, in the final days of 1659, the work was completed and Pierre Aubert took up his new property. The sculpted décor including the sumptuous main staircase was entrusted to brothers Gaspard and Balthazar Marsy and to Martin Desjardins.

The Hôtel Salé is a typical Mazarin building, whose style is marked by a revival of architectural forms, under the influence of new patrons like Pierre Aubert or Nicolas Lambert who a few years earlier had commissioned Louis Le Vau to design his house. The Italian baroque, introduced by Cardinal Mazarin, was in fashion inspiring architects to take new approaches to space, which they combined with François Mansart’s legacy of introducing classicism into Baroque architecture in France. An innovation of the time, the Hôtel Salé comprised two corps de logis, two lines of rooms which extended the building’s surface area.

Its footprint is asymmetrical: the façade giving onto the courtyard is divided in two by a perpendicular wing that separates the main courtyard from the rear courtyard. The courtyard, following a wide curve that energises the façade, reflects the innovations of the time. The façade itself is punctuated by seven open bays to emphasise the central avant-corps on three levels.

The classical pediment of the small avant-corps is a nod to Mansart; above it, the immense pediment emblazoned with acanthus, fruit and flower motifs looks towards the Baroque style. The abundance of sculpture (sphinxes and cupids) also suggest the general Baroque character of the façade. The façade overlooking the garden is less ornate.

The central staircase is the masterpiece of the house and has just been entirely restored to its original condition. It is based on the stair plan designed by Michelangelo for the Laurentian Library in Florence. Instead of a closed staircase, two Imperial flights of stairs are overlooked by a projecting balcony and then a gallery. Combining multiple effects of perspective and high-angle views, the staircase resembles a theatre. As for the sculpted stucco, French historian Jean-Pierre Babelon’s description of it as a “sort of physical translation of Hannibal Carache’s paintings in the Farnese Gallery” still holds true with eagles holding a lightning bolt, cupids adorned in garlands, Corinthian pilasters and various divinities vying for attention.

Finally, in 1660, Pierre Aubert de Fontenay purchased various properties that obstructed access to Rue Vieille-du-Temple by their gardens. Among them, a real tennis court housing the Théâtre du Marais from 1634 to 1673, where Corneille created his first plays and for which Pierre Aubert maintained the lease to allow the actors to continue to practise their art.

However, Pierre Aubert was unable to enjoy the sumptuous surroundings for very long, since in 1663 he was brought down by the same scandal that ruined Fouquet, the Superintendent of Finances! After his fall, the splendid house was coveted by a number of creditors. The legal proceedings lasted for 60 years. During this time, occupants included the Embassy of the Republic of Venice before the house was sold in 1728. In 1790, the house was sequestered and used during the French Revolution as a place to store and take an inventory of the books discovered in the local convents. It was sold again in 1797 and stayed in the same family until 1962. During this period, it was leased to various institutions: the Ganser-Beuzelin boarding school, where Balzac studied; the municipal École centrale des arts et manufactures (prestigious engineering school) (1829-1884), which made significant modifications to the building interior; Henri Vian, a master bronze-maker, followed by a consortium carrying out the same activity (until1941), and then, in 1944, the building was occupied by the City of Paris École des Métiers d’Art. The City acquired the house in 1964 and the property was granted Historical Monument status on 29 October 1968. None of its original contents remain. From 1974 to 1979, the hotel was restored and returned to its former spaciousness, before Roland Simounet was commissioned for its renovation.

To find out more : BABELON Jean-Pierre, « La maison du Bourgeois gentilhomme, l’Hôtel Salé, 5 rue de Thorigny, à Paris », Revue de l’art, année 1985, volume 68, n°68, p.7-34. Link (in French).

View of the entrance from Rue de Thorigny

Click Refresh to view slides