Wikipedia

The history of rail transport in France dates from the first French railway in 1823 to present-day enterprises such as the AGV.

Beginnings

During the 19th century, railway construction began in France with short lines for mines. The building of the main French railway system did not begin until after 1842, when a law legalised railways.

In 1814, the French engineer Pierre Michel Moisson-Desroches proposed to Emperor Napoleon to build seven national railways from Paris, in order to travel “short distances within the Empire”.

In 1823, a royal decree authorized the first railway company (Saint-Étienne to Andrézieux Railway) and the line was first operated in 1827, for goods, and for passengers in 1835. From 1830 to 1832, the line from Saint-Étienne to Lyon was opened, for goods and passengers, becoming the first passengers line of continental Europe. In that time Saint-Étienne was an important coal and iron industry center and Lyon was the main town in the south of France.

French railways started later and developed more slowly than those in certain other countries. While the first railway built in France started operation in 1827, not long after the first line had opened in Britain, French progress failed to keep pace over the next decade. Thus France quickly fell behind Germany, Belgium and Switzerland in terms of trackage per person. The rapid growth in the United States and in the United Kingdom also seriously outdistanced that in France. Circumstances did not favour a start as early and as successful as Britain’s, because Britain generally had a higher level of industrialisation. Other more comparable nations, such as Belgium, embarked on large railway-building projects soon after the technology appeared. France also suffered the handicap of the destruction and turbulence of the Napoleonic Wars and the subsequent process of rebuilding, which also hindered the development of railways. It took a full decade to begin railway construction on a national scale.

France’s history and level of development almost certainly account for this delay. France’s economy in 1832 had not developed sufficiently to support a national railway network. The limited iron industry for many years forced French railways to import many of their rails from England at great cost. French coal supplies also remained under-developed compared to those of England and Belgium. Until these complementary industries developed, French railways were at an economic disadvantage compared to those of other states.

Another obstacle to French railway development was the powerful opposition to the changes that railways would bring. For example, in 1832, the Rouen Chamber of Commerce opposed a rail link between Rouen and Paris, arguing it would be detrimental to agriculture, hurt the traditional way of life, and impinge upon the business of the canals and rivers. This last argument emerged commonly throughout France. Unlike Russia or Germany, which had no well-developed canal systems, France had a great deal of capital invested in water-borne transport. These interests saw the railways as dangerous competition. The origins of this opposition stem from France’s geography. France was naturally endowed with many navigable waterways, and also with much terrain suitable for the construction of canals. Much of France also lies not far from the coast, and coastal shipping successfully and cheaply carried much trade. Thus, the interests which profited from canals, river, and coastal shipping all used their sway in government to limit the construction of railways. While other countries, such as Britain, already utilised canals and coastal shipping well, these nations had no government-controlled railways, and thus the vested interests of water-borne trade were less able to oppose new competition.

Catholic priests bless a railway engine in

Calais, 1848

In France, existing interests combined with popular worries about the introduction of railways, especially concerning their safety. While those in opposition to railway development certainly remained a minority, their presence was larger in France than in most other industrialising nations. Since French rail development depended on government initiatives, French opponents had a clearer target to oppose than in countries where completely private companies constructed new railways.

The central involvement of government in French railways also slowed their construction, as it took time to forge a national railway policy. Under the July Monarchy, France became a far more democratic state than most others in Europe. While most of the numerous individual German states had strong central authorities, decisions in France needed to survive lengthy debates in parliament. France also exhibited considerable internal divisions within the state. Belgium, with its extremely unified political class just after independence (1830), could quickly embark on elaborate railway projects. France, however, remained long divided among liberals, conservatives, royalists and democrats, with laissez-faire liberals consistently holding a great deal of parliamentary power. All of the parties supported some form of governmental rail initiative, but they all had differing visions of the shape of that initiative. The parliament thus rejected all major rail projects before 1842, and during this period France steadily fell behind the nations that had reached quick consensus on railway policy.

The French rail system could not develop successfully without the involvement of the state. Unlike Great Britain or the United States, France had no large substantial industrial base willing to pay for railways to bring its products to new markets. French investment capital also lagged considerably behind the amounts available in Great Britain. Early troubles, such as the failed Paris to Rouen line, only reinforced the deep conservatism of the French banks. French private industry had not the strength to construct a railway industry unassisted by government. Thus, during the period of inaction by the government before 1842, the French built only small and scattered railway lines.

The eventual relationship created between the French rail system and the government formed a compromise between two competing options:

- the completely laissez-faire free-market system that had created Britain’s elaborate rail network

- a government-built and government-controlled railway, such as had grown up in Belgium.

France employed a mixture of these two models to construct its railways, but eventually turned definitively to the side of government control. The relationships between the government and private rail companies became complicated, with many conflicts and disagreements between the two groups.

Government intervention

Development of the network up to 1860

The 1842 agreement proved the most important piece of railway legislation. It aided the companies by having the department of the Ponts et Chaussées do most of the planning and engineering work for new lines. The government would assist in securing the land, often by expropriation. The government also agreed to pay infrastructure costs, building bridges, tunnels and track bed. The private companies would then furnish the tracks, stations and rolling stock, as well as pay the operating costs.

This general policy, masked many exceptions and additions. The most successful companies, especially the Compagnie du Nord, would often build their own lines themselves in order to avoid the complications of going through government. For instance, during the economic boom period of the 1850s, the national government had to pay only 19 percent of the costs of railway construction. Other less successful lines, such as the Midi, would often need more assistance from the government to remain in operation. The same proved true during recessions, such as in 1859, when the railway lines gained a new agreement to save them from bankruptcy. In exchange for funding part of the construction of rail lines, the French government set maximum rates that the companies could charge. It also insisted that all government traffic must travel at a third of standard costs.

The expectation that the government would eventually nationalise the rail system formed another important element in French railway legislation. The original agreement of 1842 leased the railway lines to the companies for only 36 years. Napoleon III extended these leases to 99 years soon after he came to power. That the rail companies only operated on leases paved the way for the nationalisation of the French rail lines under the socialist government of the 1930s.

The French rail policy, once put in place, had its deficiencies, but one certainly cannot consider it a failure, and other powers attempting to encourage rail developments adopted many aspects of the French railway laws. The bureaucratisation and influence of special interests associated with all governments, even those of corporations, also negatively affected the French railways. However, the French rail system had failed to grow on its own and required government intervention to expand successfully. While the alleged intrusion of government into the railway sector caused problems, it also proved necessary and inevitable.

Unlike in countries where the construction of railways became a field for private enterprise, the state constructed the bulk of the French railway system, and magnanimously invited private companies to operate the lines under leases (of up to 99 years). France’s railways form a somewhat unusual case in that they have never been privately owned. The state guaranteed the dividends of the railway operating companies, and in exchange took two-thirds of any greater profits.

The close relationship between the rail companies and government has much to do with French history. France had long had a large and elaborate bureaucracy and governmental structure that regulated many areas of French life. This bureaucracy survived the revolutionary period intact and played an important role in every government that ruled France in the nineteenth century. Thus, when railways arose, there already existed well-established governmental structures and procedures that could easily expand to encompass railway regulations as well. This regulatory régime, through the professional and powerful department of the Ponts et Chaussées, had very close control over the construction of roads, bridges and canals in France; therefore, it was inevitable that the new railways would also fall under the government’s close scrutiny.

Other reasons also led the French government to control its railways closely. Unlike the United Kingdom or the United States, France as a European continental power had pressing military/strategic needs from its railways, needs which a private sector might not provide. The French government constructed long stretches of strategic railways in eastern France along the German border that served strategically crucial ends, but lacked economic viability. “Pure” private economic interests would not have constructed these routes on their own, so France used government rewards and pressure to encourage the rail companies to build the needed lines. (The German and Russian Empires also had widespread strategic railway systems that private companies would not have built appropriately.)

The first completed lines radiated out of Paris, connecting France’s major cities to the capital. These lines still form the backbone of the French railway system. By the 1860s, workers had completed the basic structure of the network, but they continued to build many minor lines during the late 19th century to fill in the gaps .

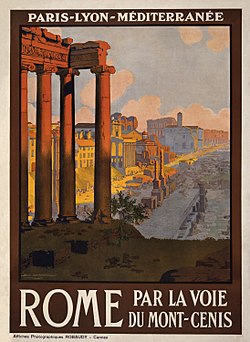

Government involvement in the railroads did mean that the French rail system became based on a very inefficient design. By 1855, the many original small firms had coalesced into six large companies, each having a regional monopoly in one area of France. The Nord, Est, Ouest, Paris-Orléans, Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM), and the Midi lines divided the nation into strict corridors of control. Difficulties arose in that the six large monopolies, with the exception of the Midi Company, all connected to Paris, but did not link together anywhere else in the country. The French railway map comprised a series of unconnected branches running out of Paris. While this meant that trains served Paris well, other parts of the country were not served as well. For instance, one branch of the Paris-Orléans Line ended in Clermont-Ferrand, while Lyon stood on the PLM Line. Thus any goods or passengers requiring transportation from Lyon to Clermont-Ferrand in 1860 needed to take a circuitous route via Paris of over seven hundred kilometers, even though a mere hundred and twenty kilometers separated the two cities.

This grave inefficiency lead to great problems in the Franco-Prussian War (1870 – 1871). The German railway lines, inter-connected in a grid-like fashion, proved far more efficient at advancing troops and supplies to the front than the French one. “Combien nous a été funeste l’absence de lignes transversales […] unissant nos grandes artères” reported a military officer to the parliamentary inquiry on France’s defeat.

The arrangement of the lines also hurt France’s economy. Shipping costs between regional centres became greatly inflated. Thus many cities specialised in exporting their goods to Paris, as trans-shipment to a second city would double the price.

France ended up with this regressive arrangement for a number of reasons. Paris formed the undisputed capital of France, and many viewed it as the capital of Europe. To French railway planners, it seemed only natural that all the lines should involve the metropolis. By contrast Germany ended up with a far superior system because it had little unity and many centers vying for preeminence. Thus a variety of rail centres arose. Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Hamburg, and the Rhine areas all had links to each other.

The French railway lines also exhibited a high degree of centralisation because plans dictated this. Unlike Britain and America, France had a central government which greatly influenced the layout and the planning of the railways. This Paris-centric government had minimal local representation, especially in the bureaucracy. The Ponts et Chaussées department that supervised the railways remained thoroughly Parisian. Because of strong governmental and administrative influence, all six of the French railway companies had their headquarters in Paris. This occurred not only because of the unquestioned centrality of Paris, but also because the rail companies always remained in close contact with the French government, and needed bases in Paris to ensure positive relations.

Nineteenth-century Britain largely lacked intensive government interference in the railways. Railway companies thus experienced less pressure to centre their lines on London, and also less necessity for each company to cultivate such close links to the centre of political power. In England, for instance, local businesses financed and promoted the Stockton & Darlington and Liverpool & Manchester lines. In France, cities like Lyon and Bordeaux did not have many wealthy investors – capital emanated almost exclusively from Paris. This concentration of capital in Paris also contributed to the concentration of the railway system in the metropolis.

The most important of the railway operating companies during this period included:

By 1914 the French railway system had become one of the densest and most highly developed in the world, and had reached its maximum extent of around 60,000 km (37,000 mi). About one third of this mileage comprised narrow gauge lines.

Following the First World War, France received significant additions to its locomotive and wagon fleet as part of the reparations from Germany required by the Versailles Treaty. In addition the network of the Imperial Railways in Alsace-Lorraine was taken over by France when the Alsace-Lorraine region, which had been under German control since the Franco-Prussian War, was returned to France.

Nationalisation

By the 1930s, road competition began to take its toll on the railways, and the rail network needed pruning. The narrow gauge lines suffered most severely from road competition; many thousands of miles of narrow gauge lines closed during the 1930s. By the 1950s the once extensive narrow gauge system had practically become extinct. Many minor standard gauge lines also closed. The French railway system today has around 40,000 km (25,000 mi) of track.

Many of the private railway operating companies began to face financial difficulties. In 1938 the socialist government fully nationalised the railway system and formed the Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Francais (SNCF). Regional authorities have begun to specify schedules since the mid of the 1970s with general conventions between the regions and the SNCF since the mid-1980s.

From 1981 onwards, a newly constructed set of high-speed TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) lines linked France’s most populated areas with the capital, starting with Paris-Lyon. In 1994, the Channel Tunnel opened, connecting France and Great Britain by rail under the English Channel.

See also

References

- Caron, François. Histoire des Chemins de Fer en France. Paris: Fayard, 1997.

- Clapham, J. H. The Economic Development of France and Germany, 1815-1914. Cambridge University Press, 1961.

- Doukas, Kimon A. The French Railroads and the State. Columbia University Press, 1945.

- Dunham, Arthur. “How the First French Railways Were Planned.” Journal of Economic History. Vol. 1, No. 1. (1941), pp. 12–25 in JSTOR

- Lefranc, Georges. “The French Railroads, 1823-1842”, Journal of Business and Economic History, II, 1929–30, 299-331.

- Mitchell, Allan. The Great Train Race: Railways and the Franco-German Rivalry, 1815-1914. Berghahn Books, 2000.

- Sterne, Simon. “Some Curious Phases of the Railway Question in Europe.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 1, No. 4. (1887), pp. 453–468. in JSTOR