Old Maps of Paris

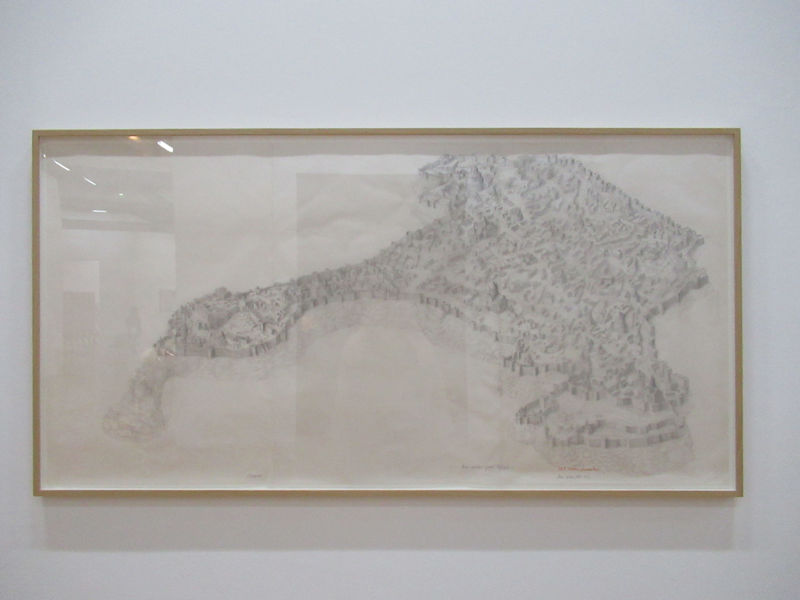

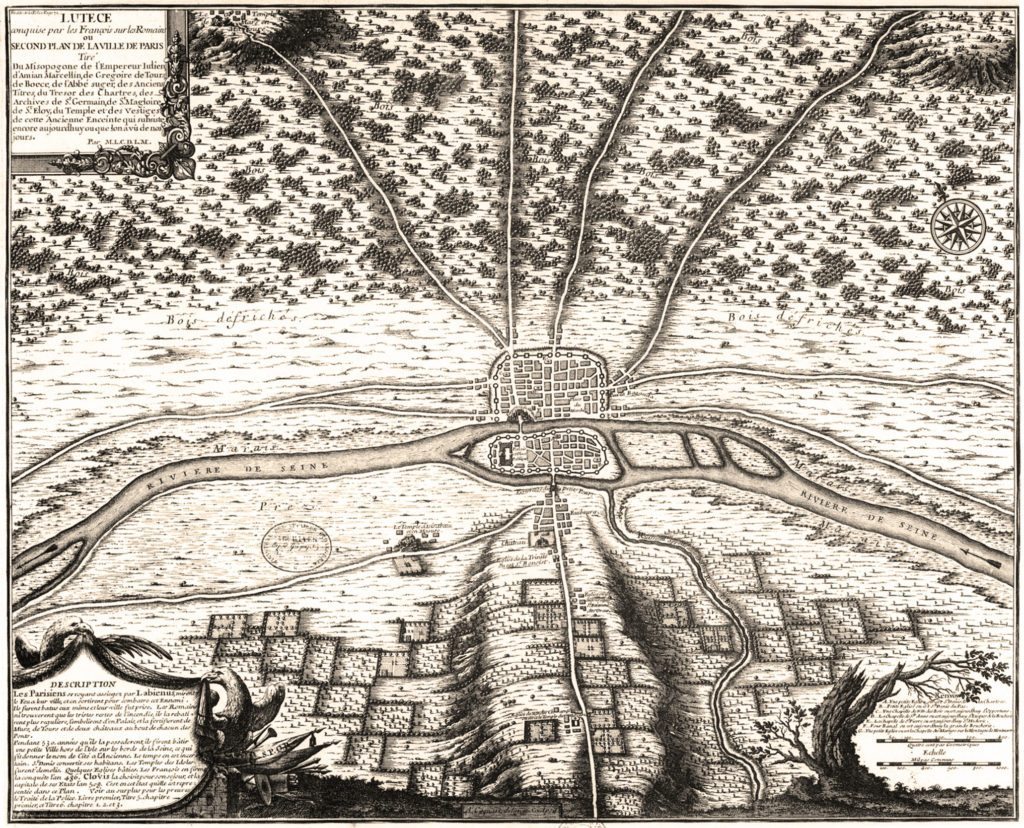

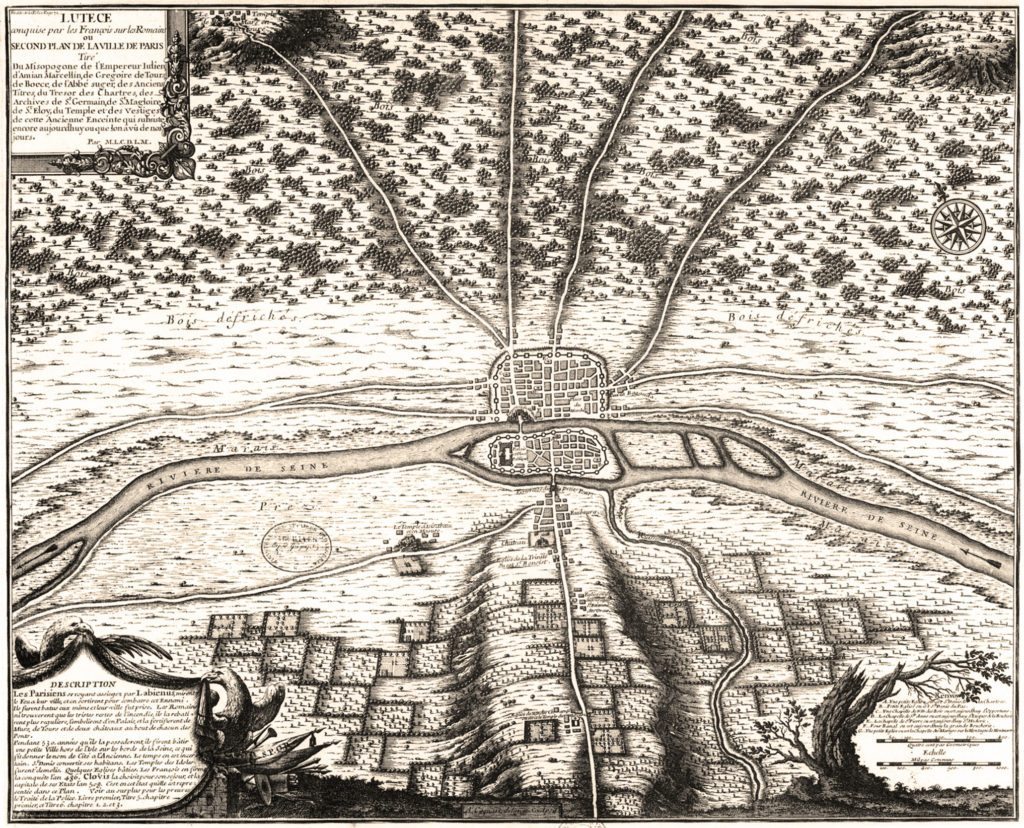

Paris (Lutèce) Circa 508

Clovis I, who in 481 became king at 16 years of age, made Paris his capital in the year 508. Clovis I is considered to be the founder of the Merovingian Dynasty, which ruled the Frankish kingdom for the next 200 years. He was the king of the Franks who would successfully unify all Frankish tribes into one kingdom under one ruler.

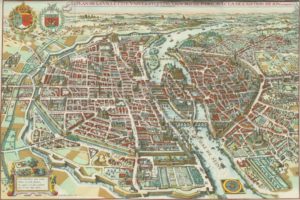

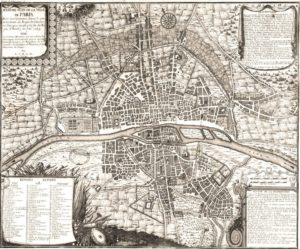

Paris Circa 1422

In 1466, perhaps 40,000 people died of the plague in Paris. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the black plague visited Paris for almost one year out of three.

France is under the rule of House of Valois with the death of Charles VI. After the death of King Charles VI, King Henry VI of England (House of Lancaster), becomes regent of France after the Treaty of Troyes. His rule lasts from 1422 to 1453. At the same time Charles VII also claims the throne with the death of his father.

The House Valois of France rules until 1589 when The House of Bourbon inherits the throne.

Maps after this date will indicate the growth that followed this period.

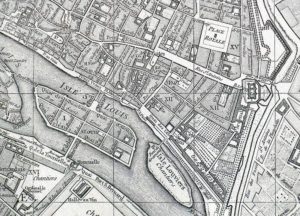

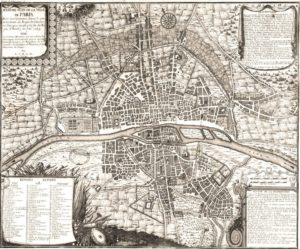

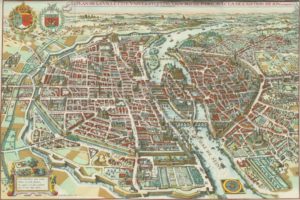

Paris 1615 Plan De Mérain

The construction of the Luxembourg Palace and gardens begins in 1615.

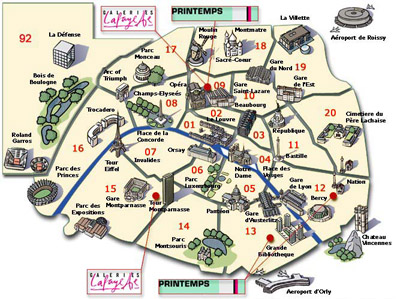

The geography of Paris – from paris-city.fr

Paris, the capital of France and of the Ile de France region, covers a surface area of 105 km² and has a population, according to the last census in 1999, of 2,125,246. At the end of the 20th century, the Paris agglomeration counted 11,131,412 inhabitants, of which 2,147,274 within the city proper.

Parisians make up 19.4% of the population of the Ile de France region (estimated 1st January 2003). The overall population of the region has been in constant decline for over 70 years.

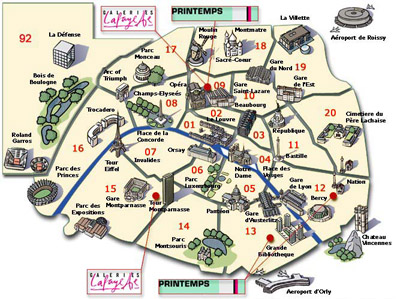

Paris is administrative department 75, and within the department, the city is divided into 20 administrative arrondissements. The arrondissements are set out in the form of a spiral, with the first arrondissement in the centre and the numbers increasing outwards in a clockwise direction.

Paris occupies the heart of a sedimentary basin in the western reaches of the great plains of Northern Europe. In the centre of the fluvial plain of the Seine, the city lies just downstream of the Seine-Marne confluence and upstream of the confluence with the Oise. The naturally occurring waterway crossroads explains the existence and exceptional development over fifteen centuries of this urban pole.

More precisely, Paris formed around the l’île de la Cité at the junction of two great waterways. The north-south axis weaves between the hills of Montmartre and Belleville over the hillock of la Chapelle, the gateway to gares du Nord et de l’Est and the Saint-Martin canal.

More precisely, Paris formed around the l’île de la Cité at the junction of two great waterways. The north-south axis weaves between the hills of Montmartre and Belleville over the hillock of la Chapelle, the gateway to gares du Nord et de l’Est and the Saint-Martin canal.

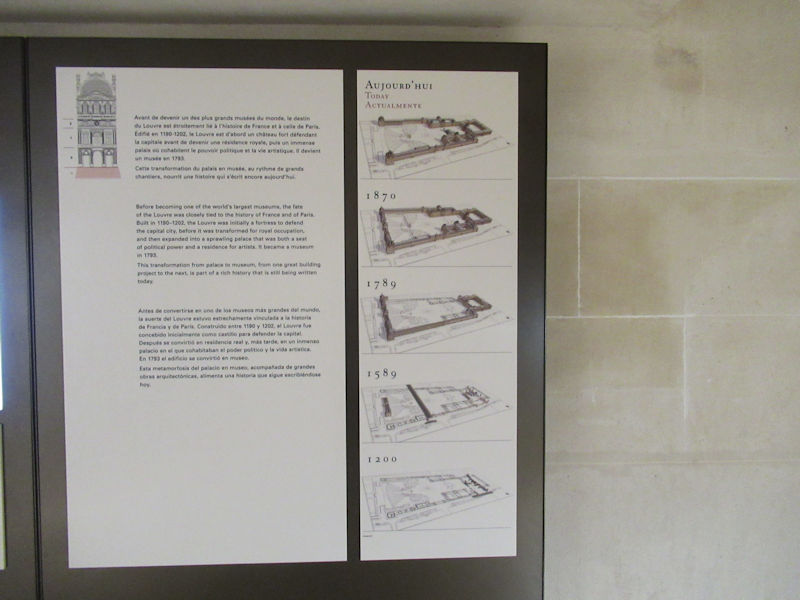

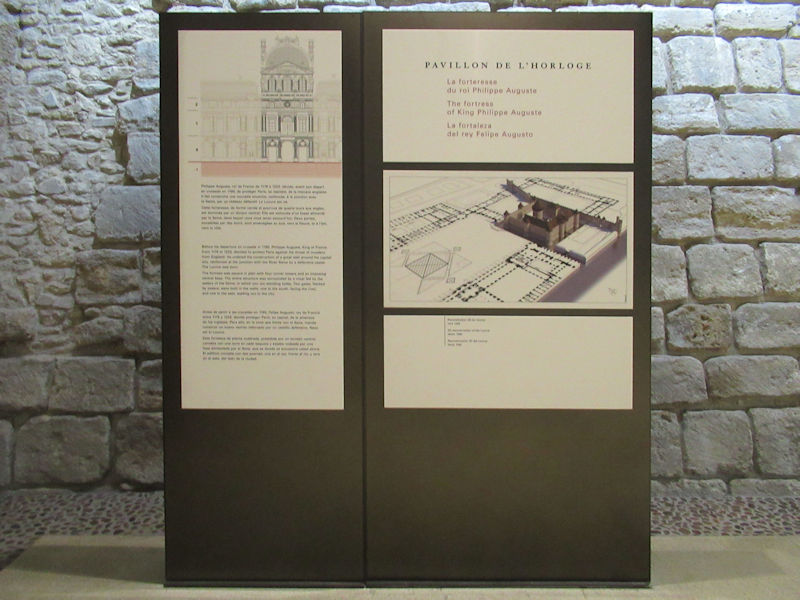

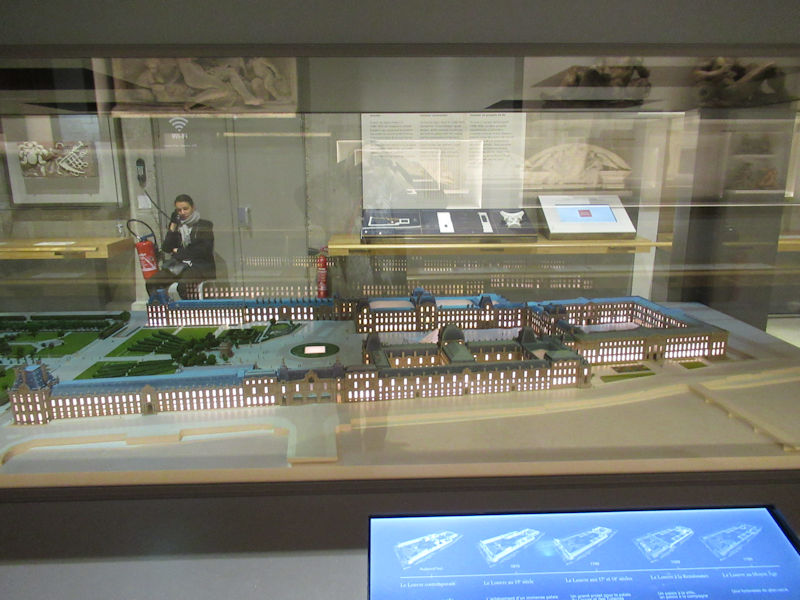

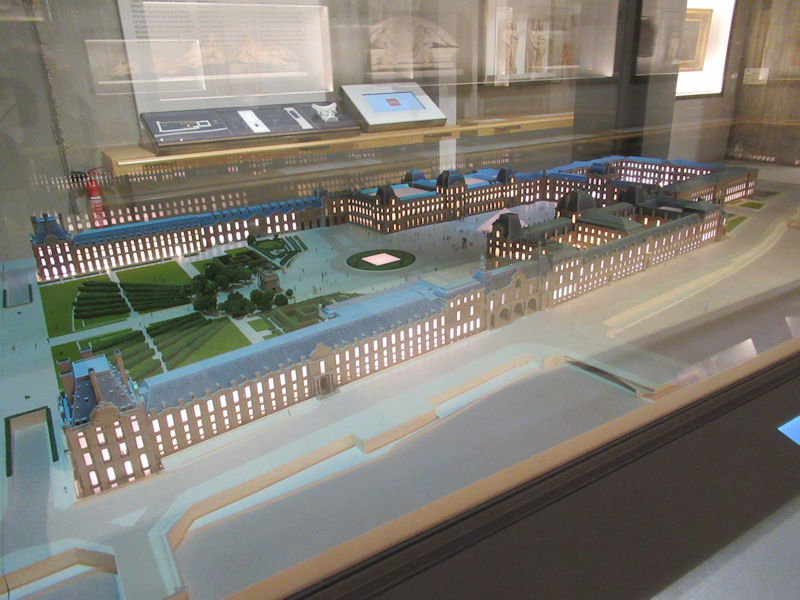

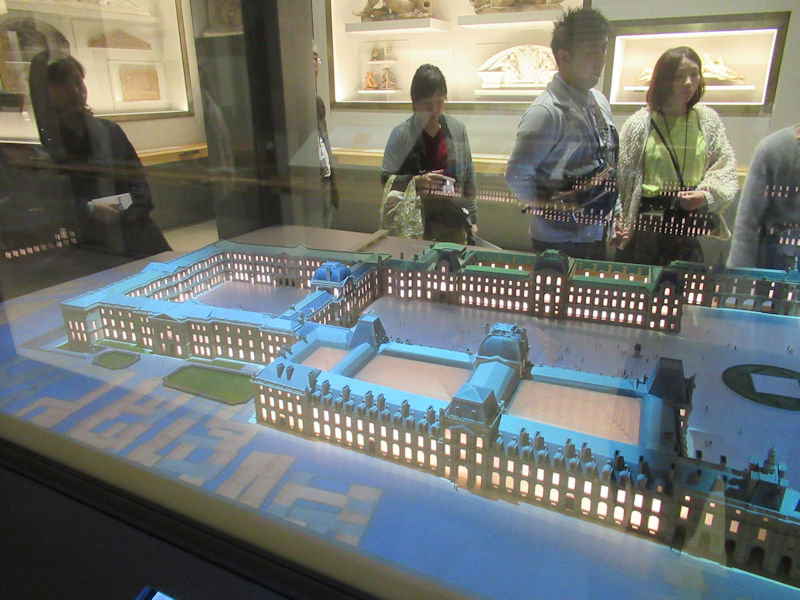

At Châtelet in the centre, the east-west axis runs alongside the Seine on the right bank, through la Bastille, the Louvre and the Champs-Élysées, over to the suburbs in Chaillot and beyond, la Défense.From there, the axis runs along Rue Saint-Martin and Rue Saint-Denis, crosses the Seine at the pont au Change and climbs up the right bank, following the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève.

This axis was followed underground when the first metro line was built, inaugurated in 1900, the line ran from Porte Maillot to Vincennes (later extended to Neuilly in the west). This route through the city is dotted with prestigious monuments, which, together with the presence of Place de l’Etoile and Nation at either end of the line, then the forests of Vincennes and Boulogne beyond, demonstrates the east-west symmetry of the city. City facts : Insee

This axis was followed underground when the first metro line was built, inaugurated in 1900, the line ran from Porte Maillot to Vincennes (later extended to Neuilly in the west). This route through the city is dotted with prestigious monuments, which, together with the presence of Place de l’Etoile and Nation at either end of the line, then the forests of Vincennes and Boulogne beyond, demonstrates the east-west symmetry of the city. City facts : Insee

The UNESCO has classified as a collective world heritage site over 30 bridges that cross the Seine in Paris, from Pont-Neuf, completed in 1607, to Pont Charles de Gaulle, inaugurated in 1996. Upriver, the banks of the Seine have changed radically since the 1980’s; the right bank has seen the emergence of the ZAC (Concerted Development Zone) at Bercy, with the new Ministry of the Economy rising above the river.

The opposite bank is occupied by the big construction zone of Tolbiac, dominated by the four towers of the National Library, now called the Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand (architect : Dominique Perrault). Once past the gare de Lyon (right bank) and the d’Austerlitz (left bank), the Seine moves into the historical heart of Paris, flowing around the little islands of Ile Saint-Louis and Ile de la Cité.There, in an area of less than 20 hectares, are gathered the Cathedral Notre-Dame, the Hôtel-Dieu and, inside the walls of the old royal palace, Sainte-Chapelle and the Palais de justice. Just across the river, on the right bank, stands the Hôtel de ville.Beyond, the Seine stretches before the long colonnade of the Louvre.

The opposite bank is occupied by the big construction zone of Tolbiac, dominated by the four towers of the National Library, now called the Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand (architect : Dominique Perrault). Once past the gare de Lyon (right bank) and the d’Austerlitz (left bank), the Seine moves into the historical heart of Paris, flowing around the little islands of Ile Saint-Louis and Ile de la Cité.There, in an area of less than 20 hectares, are gathered the Cathedral Notre-Dame, the Hôtel-Dieu and, inside the walls of the old royal palace, Sainte-Chapelle and the Palais de justice. Just across the river, on the right bank, stands the Hôtel de ville.Beyond, the Seine stretches before the long colonnade of the Louvre.

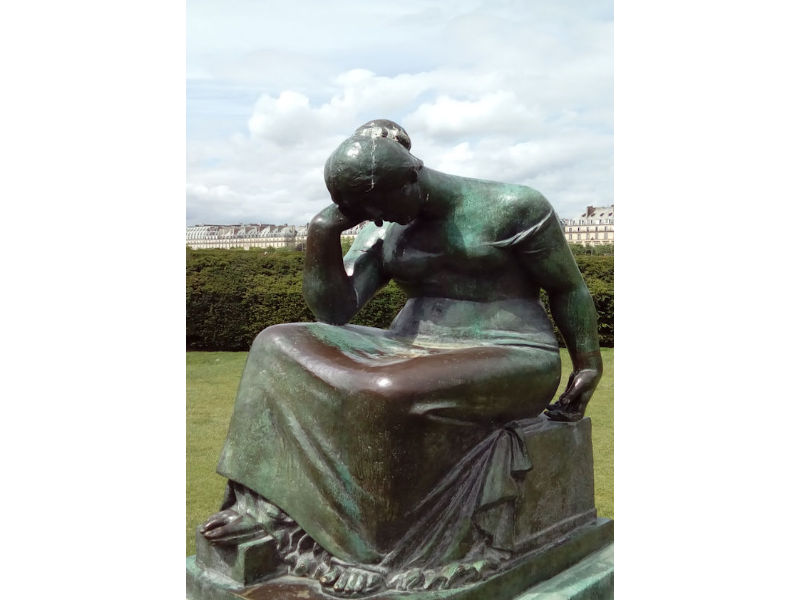

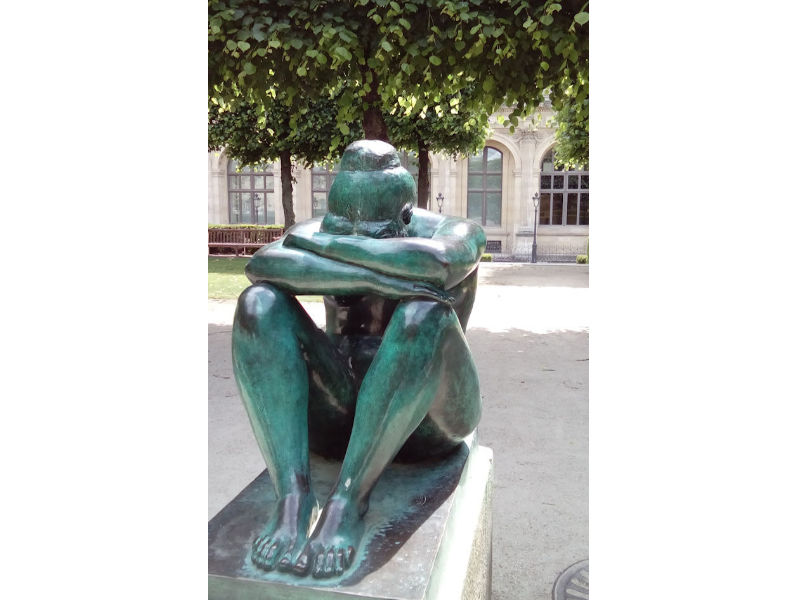

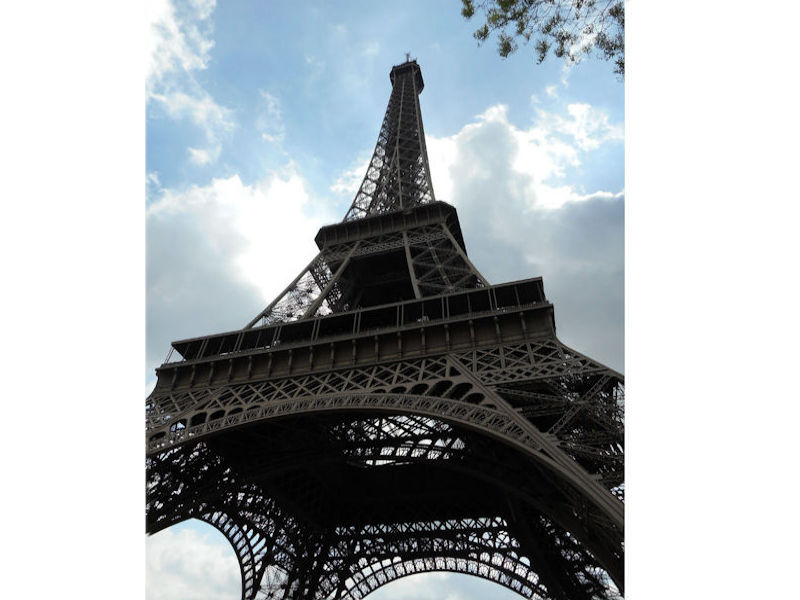

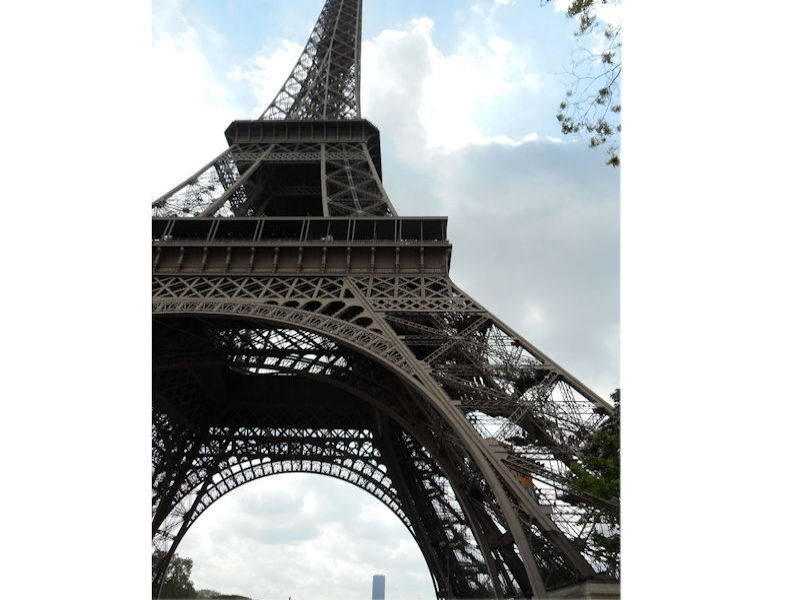

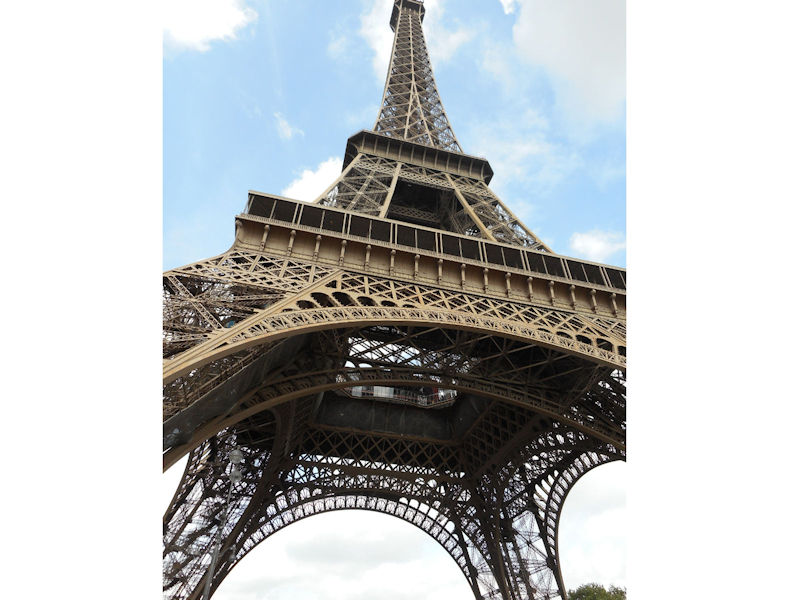

Further to the west are the Jardin des Tuileries and Place de la Concorde on the right bank. The monuments here bring to mind the Universal Expositions that took place in Paris: the Eiffel tower, put in place for the exposition of 1889; the Petit et Grand Palais (1900); the Palais de Chaillot (1937).

Further to the west are the Jardin des Tuileries and Place de la Concorde on the right bank. The monuments here bring to mind the Universal Expositions that took place in Paris: the Eiffel tower, put in place for the exposition of 1889; the Petit et Grand Palais (1900); the Palais de Chaillot (1937).

Before leaving Paris the Seine passes the Maison de la Radio and the towers of operation Front de Seine. Paris has served for ten centuries as a political capital for a number of reasons: its geographical situation in the centre of the Parisian basin, which is the site of important river confluences; the busy crossroads that it naturally forms for road and rail networks, as well as busy flight paths; its easy access to the sea via the navigable river Seine; its proximity to North-Western Europe, which is one of the most concentrated industrialised and urbanised regions in the world. Paris is in a marginal position relative to the industrial axis that stretches from Rotterdam to Milan, however the putting in place a European fast rail network would largely compensate for this, making Paris the hub for transport through the channel tunnel into the U.K.

Paris has the highest rates of business activity and productivity in France. The tertiary sector alone employs 3 million people in the Greater Paris area. Almost a third of that employment stems from the city’s function as the political and administrative capital.

In other words, the standard of living is higher in Paris than anywhere else in the country. This is the result of different activities and economic processes that come with any very large city, and the snowball effect that they have on the surrounding environment. The tertiary sector grows and diversifies; while the resulting intensification of communication and transaction activities pushes the industrial sector out to the suburbs.

In other words, the standard of living is higher in Paris than anywhere else in the country. This is the result of different activities and economic processes that come with any very large city, and the snowball effect that they have on the surrounding environment. The tertiary sector grows and diversifies; while the resulting intensification of communication and transaction activities pushes the industrial sector out to the suburbs.

For some years, there has been clear increase in high-tech industries, particularly in the electronics and computer sectors, matched by a simultaneous decline in traditional industries like timber, clothing, leather and printing. What’s more, the number of businesses has decreased by 15%, or 30,000 companies, predominantly among trade activities and light industry.

Paris and the Parisian region therefore constitute one of the most complex industrial poles there is, much more even than the large industrial regions, such as La Lorraine or Le Nord. In reality, efforts to decongest the capital are constantly battling against the need to keep a sufficient mass of jobs there for the tertiary sector to be supported and developed. The array of tertiary activities being conducted in Paris and its suburbs is more and more visible as time goes on. The effect on the city is an increased demand for office space, and consequently modern office buildings rapidly springing up throughout the city. Along the axis formed by la Défense, the Champs-Élysées and Bercy, one of the most attractive tertiary sector corridors in Europe stretches over 30 km all the way from Saint-Germain-en-Laye to Marne-la-Vallée.

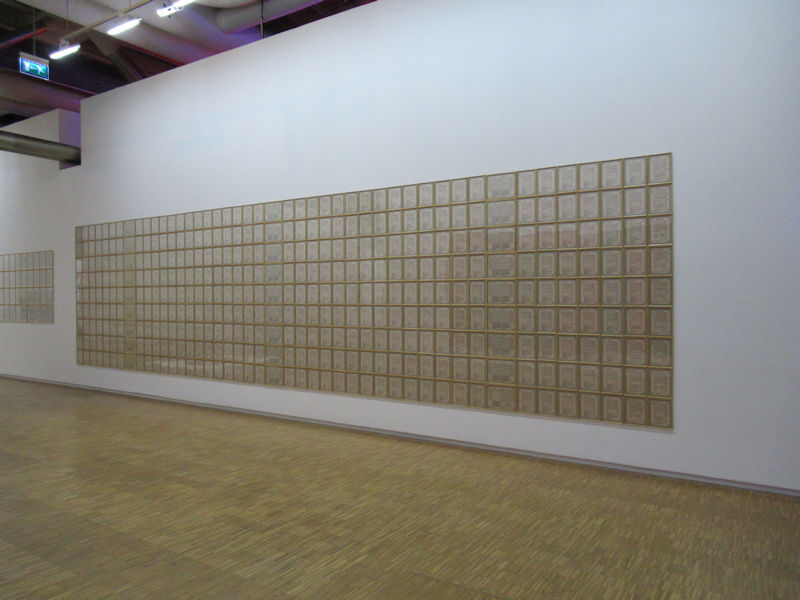

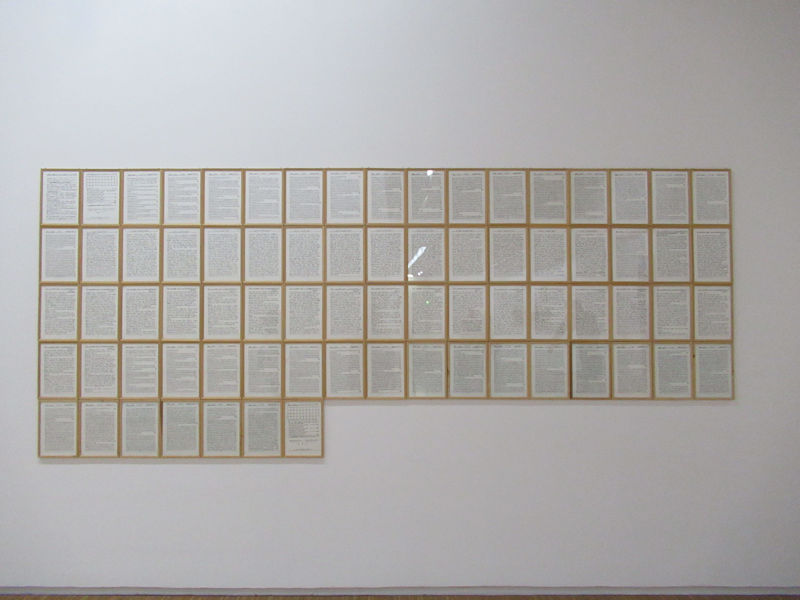

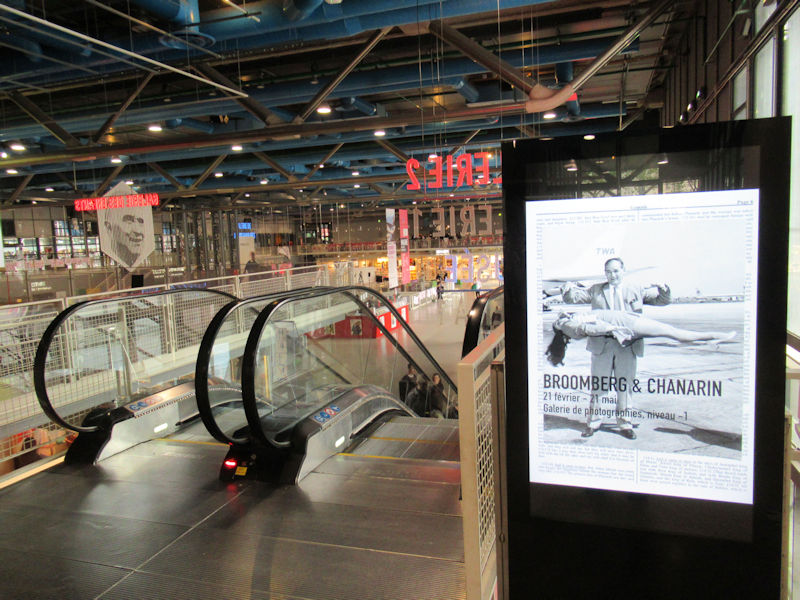

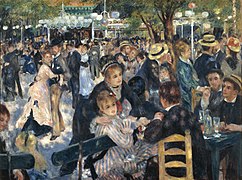

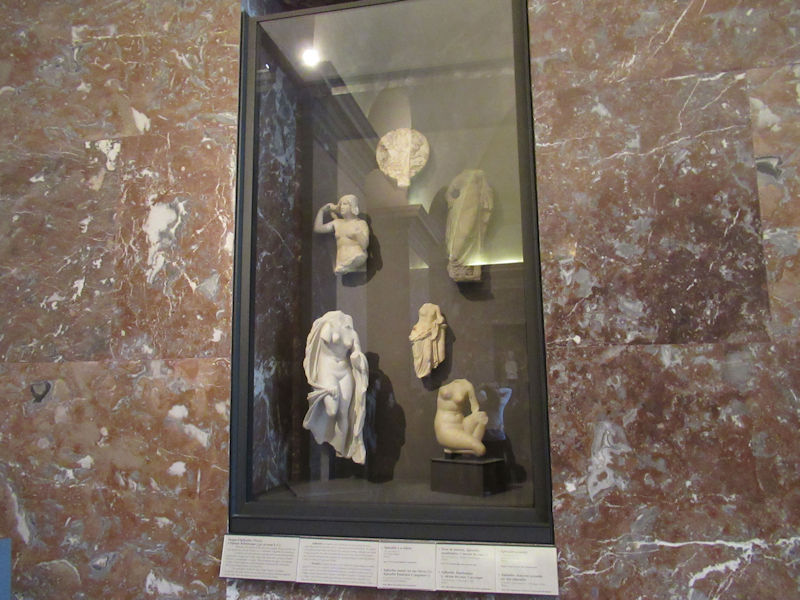

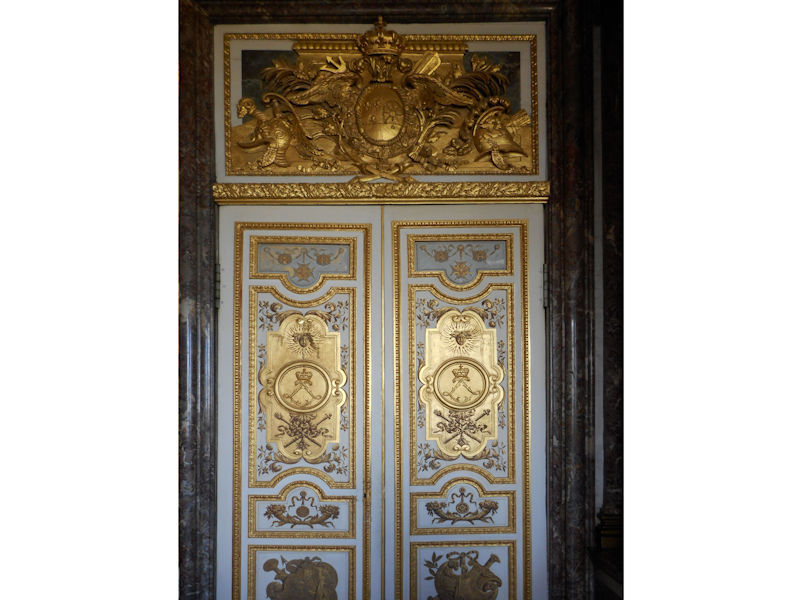

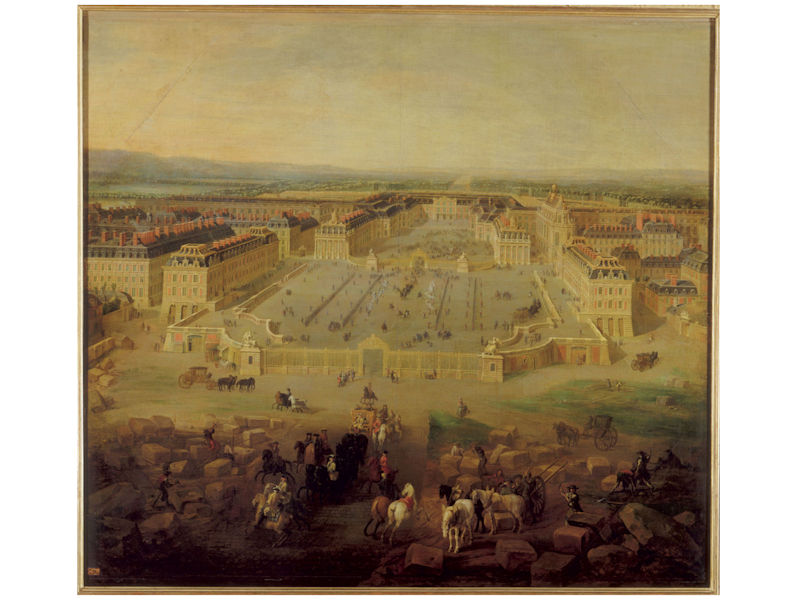

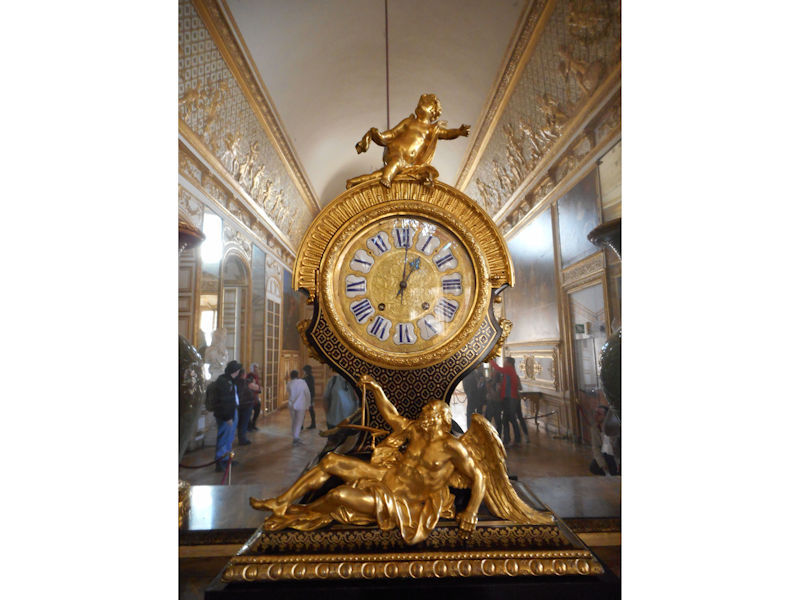

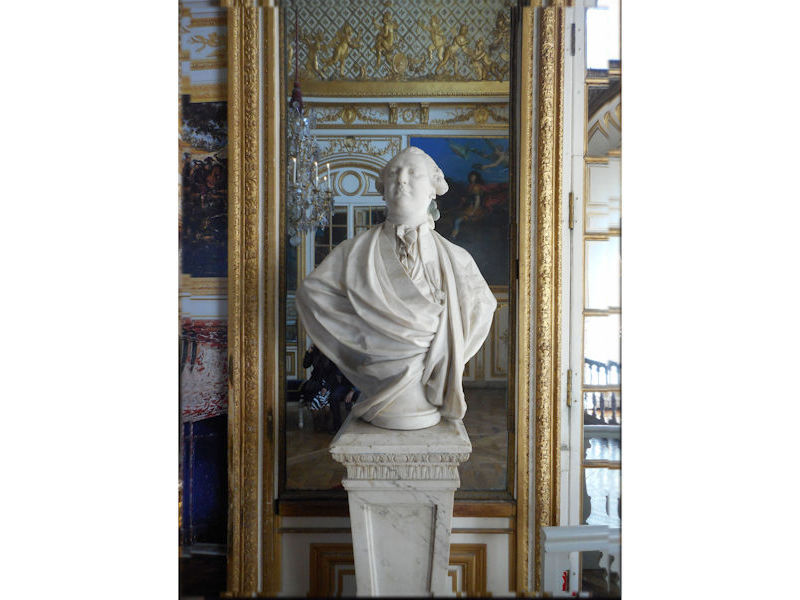

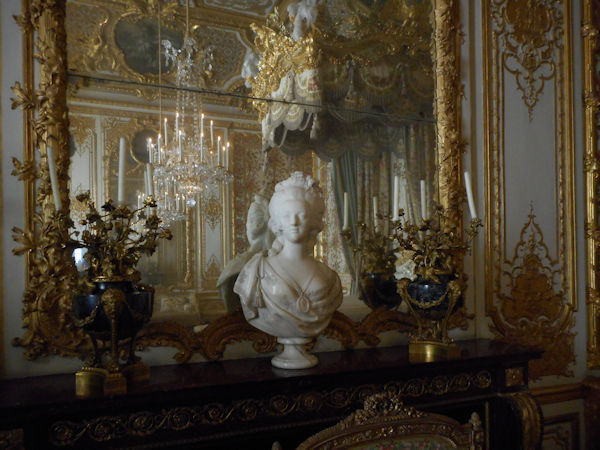

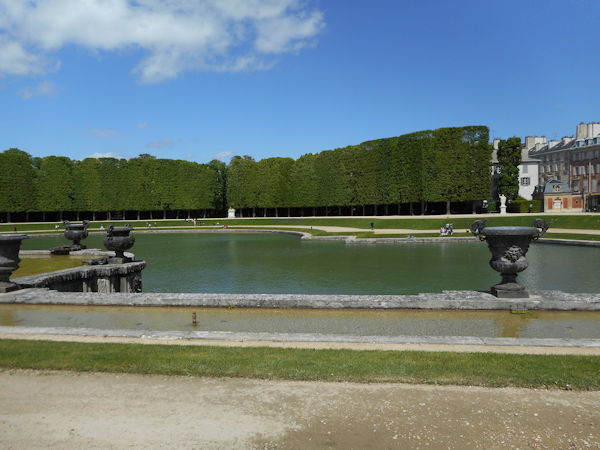

This is visibly the case, zones of industrial activity are heavily present around the outskirts of the city today, notably the automotive sector which pioneered the outward migration.The greater urban area represents a network of industries, which are linked to each other by complex relationships: the tourism sector with luxury industries, scientific research and artistic activities with high-tech industries and producers of cultural goods. Paris attracts more conferences, salons and expositions than any other city in the world. Some of the city’s attractions are visited by more than a million visitors each year, notably the Pompidou Art & Cultural Centre or the Eiffel Tower, or outside the city: Versailles or Disneyland-Paris, at Marne La Vallée. Certain monuments, of course, will always remain the must-see spectacles for tourists: the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, Montmartre, Notre-Dame, the Pantheon, the Louvre, or the Palais des Invalides. Of course, tourists also make up a great number of the visitors to the 200 museums, the 120 theatres and music venues and the hotels: 200,000 rooms are available in Ile de France, three quarters of them in the capital. The wholesale food business was radically transformed by the transfer from Les Halles to Rungis, which has become a unique centre for the redistribution of produce, not only throughout the whole of France but even overseas.

This is visibly the case, zones of industrial activity are heavily present around the outskirts of the city today, notably the automotive sector which pioneered the outward migration.The greater urban area represents a network of industries, which are linked to each other by complex relationships: the tourism sector with luxury industries, scientific research and artistic activities with high-tech industries and producers of cultural goods. Paris attracts more conferences, salons and expositions than any other city in the world. Some of the city’s attractions are visited by more than a million visitors each year, notably the Pompidou Art & Cultural Centre or the Eiffel Tower, or outside the city: Versailles or Disneyland-Paris, at Marne La Vallée. Certain monuments, of course, will always remain the must-see spectacles for tourists: the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, Montmartre, Notre-Dame, the Pantheon, the Louvre, or the Palais des Invalides. Of course, tourists also make up a great number of the visitors to the 200 museums, the 120 theatres and music venues and the hotels: 200,000 rooms are available in Ile de France, three quarters of them in the capital. The wholesale food business was radically transformed by the transfer from Les Halles to Rungis, which has become a unique centre for the redistribution of produce, not only throughout the whole of France but even overseas.

The greatest concentration of head-quarters and power centres are located in the west of the city. Since 1977, Paris has been administrated by a mayor elected by universal suffrage. Jacques Chirac was the first person to be elected to that post.

The Elysée Palace, residence of the President of the Republic, is situated on the right bank of the Seine, behind the gardens of the Champs-Elysées. The ministries are located on the other side of the river, in sumptuous buildings in Faubourg Saint-Germain (such as Hôtel Matignon, the residence of the prime minister). Nearby, and closing the perimeter inside which are gathered the central powers, the Palais Bourbon houses the Assemblée Nationale, facing Place de la Concorde, and the Palais du Luxembourg, constructed for Marie de Medici in the early 17th century, which now houses the Senate. The relocation of the Ministry for Public Facilities to the Grande Arche de la Défense didn’t very much change the geography of the official palaces.

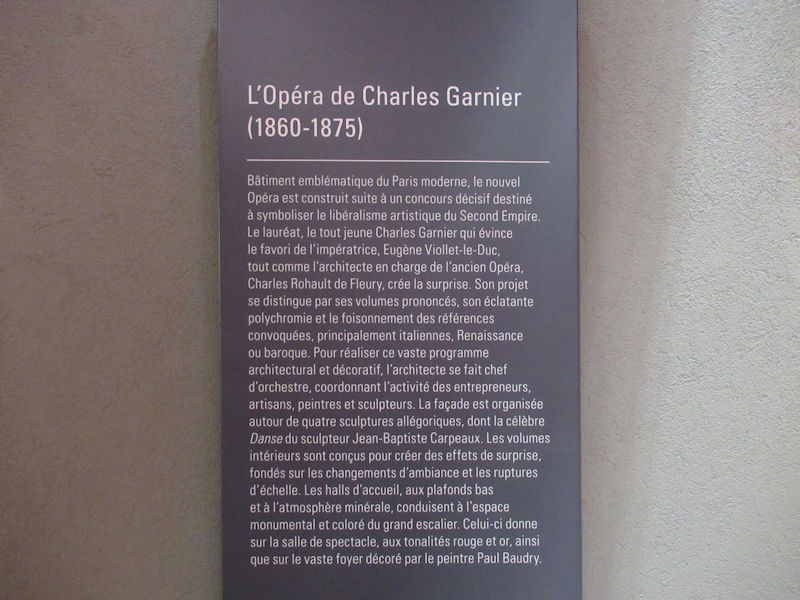

The centres of economic and financial power are almost exclusively on the right bank, in the quarters most marked by Haussmann’s works, between Opéra and Place de Étoile. This business quarter, based around the Banque de France and the stock exchange, or Bourse (1808-1826, architect Brongniart) the second in Europe after London, has been expanding steadily towards the west. There you can find the headquarters of various insurance companies, banks and big businesses, but equally the area has many luxury stores: jewellers in the Place Vendôme, big car dealerships on the Champs-Elysées and fashion houses on Avenue Montaigne.

On the left bank, within the triangle formed by the Natural History Museum, the Ecole Normale Supérieure and the Institut de France, can be found the most prestigious academic establishments in France: Sorbonne and the Collège de France . The cultural vocation of the quarter is further emphasised by the presence of numerous publishing houses and by the general literary life that animates the area around the church of Saint-Germain-des-Près.

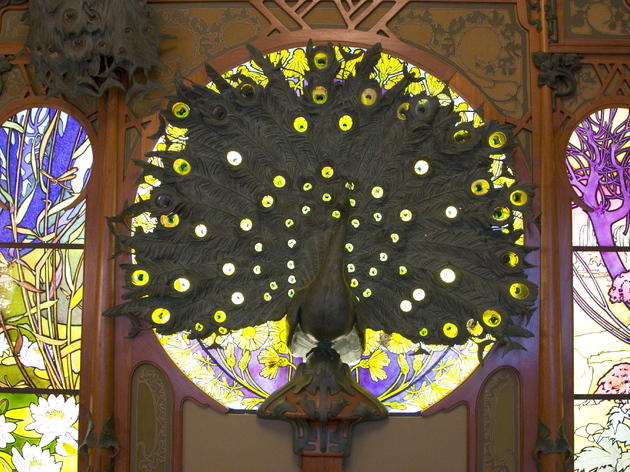

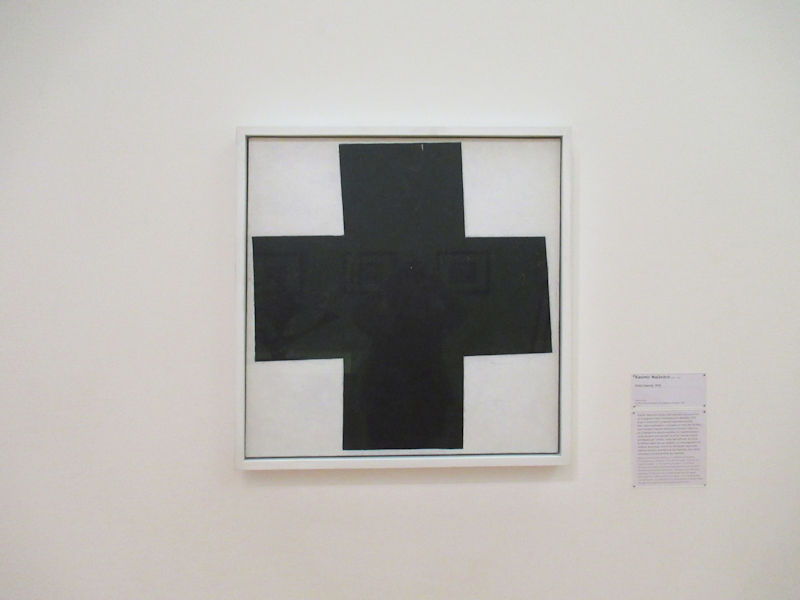

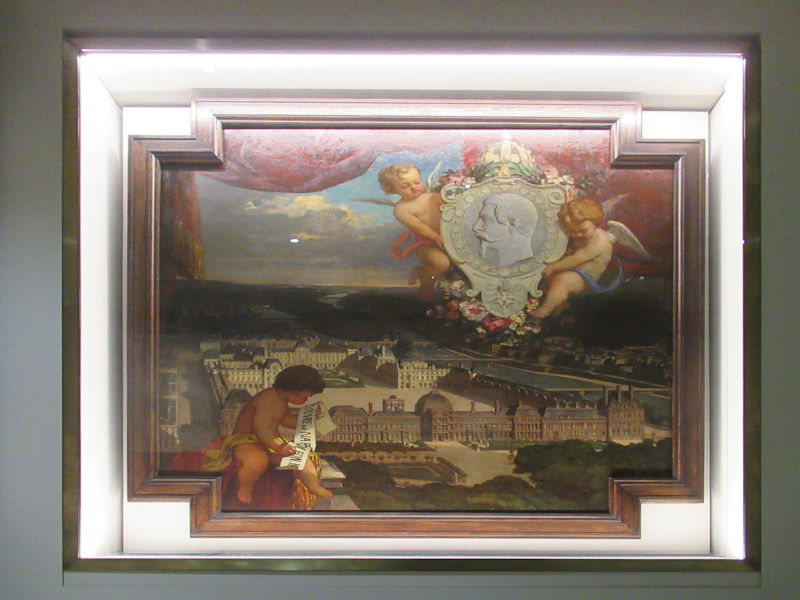

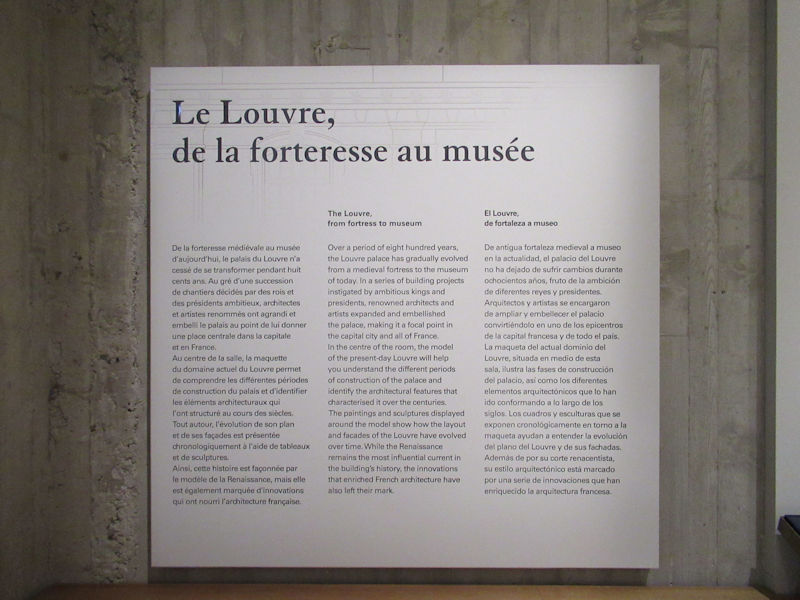

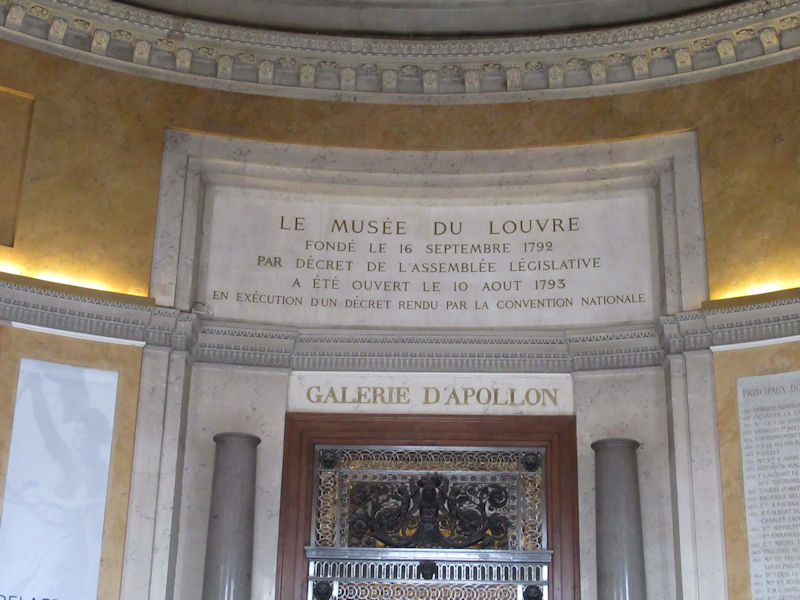

The right bank is not entirely left out: the Palais Royal, which was home to the Orleans family, was in the 18th century one of the centres of the Enlightenment movement. Napoleon I also made an impact on the right bank when he decided to transform the Louvre into a museum. With the construction of the Georges Pompidou Centre for Art & Culture, the Picasso Museum, the Cité des Sciences at La Villette and the Bastille Opera, cultural points of interest were installed in parts of the city that had, until then, been quite barren. While the west of Paris developed a bourgeois and plush character, the eastern districts have long housed a working class population and various industrial and trade activities. The story of the Commune of Paris and the inexorable march of the Versailles forces from west to east, until the Wall of the Federates in Père Lachaise cemetery, illustrate this political and social asymmetry in the city.

The presence of the Saint-Martin canal, the major freight stations (North, East, Tolbiac) and the warehouses of Bercy explains the location of materials handling and conversion activities in the north and east of the city. Bastille was traditionally the quarter of the cabinet makers, while the rug makers of “Manufacture des Gobelins” set up shop close to Place d’Italie.

The desire to rebalance the city towards the east, combined with the departure of industry from the city, brought about efforts to rapidly install tertiary activities in these districts – a prime example is the ZAC at Bercy. Simultaneously, the arrival of wealthier residents in the east of Paris is gradually changing the social composition of that part of the city.

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

Portail de Paris

Portail de Paris