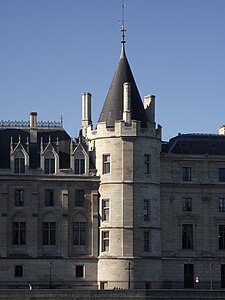

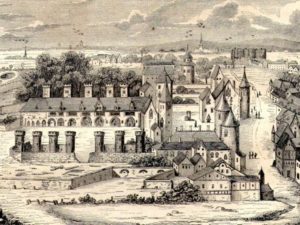

The Palais de la Cité, located on the Île de la Cité in the Seine River in the center of Paris, was the residence of the Kings of France from the sixth century until the 14th century. From the 14th century until the French Revolution, it was the headquarters of the French treasury, judicial system and the Parlement of Paris, an assembly of nobles. During the Revolution it served as a courthouse and prison, where Marie Antoinette and other prisoners were held and tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal. The palace was built and rebuilt over the course of six centuries; the site is now largely occupied by the buildings of the 19th century Palais de Justice, but a few important vestiges remain; the medieval lower hall of the Conciergerie, four towers along the Seine, and, most important, Sainte-Chapelle, the former chapel of the Palace, masterpiece of Gothic architecture. Both parts of the Conciergerie and Saint-Chapelle are classified as national historical monuments and can be visited, though most of the Palais de Justice is closed to the public.

The Palais de la Cité as it appeared between 1412 and 1416, as illustrated in the

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

Sainte-Chapelle is to the right, the royal residence is in the center, with the Grosse Tour behind it; the

Grand Salle (Great Hall) is to the left.

History

The Roman and Merovingian Palace

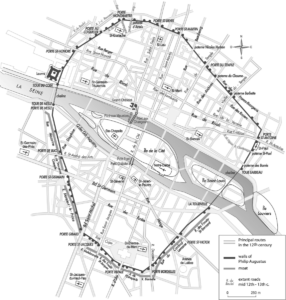

Archeological excavations have found traces of human habitation on the [Île de la Cité from 5000 BC until the beginning of the Iron Age, but no evidence that the Celtic inhabitants, the Parisii, used the island as their capital. However, after the Romans conquered the Parisii in the first century BC. the island was developed quickly. While the forum and largest part of the Roman town, called Lutetia, was on the left bank, a large temple was located on the east end of the island, where the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris is found today. The west end of the island was residential, and was the site of the palace of the Roman prefects, or governors. The palace was a Gallo-Roman fortress surrounded by ramparts. In the year 360 AD, the Roman prefect Julian the Apostate was declared Emperor of Rome by his soldiers while he was resident in the city.

Beginning in the 6th century, the Merovingian kings used the palace as their residence when they were in Paris. Clovis, the King of the Franks, lived in the palace from 508 until his death in 511. The Kings who followed him, the Carolingians, moved their capital to the eastern part of their empire, and paid little attention to Paris. At the end of the 9th century, after a series of invasions by the Vikings threatened the city, King Charles the Bald had the walls rebuilt and strengthened. Hugh Capet (941-996), the Count of Paris, was elected King of the French on 3 July 987, and resided in the fortress when he was in Paris, but he and the other Capetian kings spent little time in the city, and had other royal residences in Vincennes, Compiègne and Orleans. The administration and archives of the kingdom travelled wherever the king went.

The Capetian palace

Drawing of the Palace as it looked following the construction of Sainte-Chapelle (consecrated in 1248), by

Viollet-le-Duc

At the beginning of the Capetian dynasty, the King of France ruled little more than what is now the Île de France; but through a policy of conquest and intermarriage, they began to expand their kingdom, and to transform the old Gallo-Roman fortress into a real palace. Robert the Pious, the son of Hugh Capet, who ruled from 972 to 1031, stayed in Paris more often than his predecessors. He rebuilt the fortress in particular to meet the demands of his third wife, Constance of Arles, for greater comfort. Robert reinforced the old walls and added fortified gates; the main entrance, most likely, was on the north side. The walls surrounded a rectangle 130 meters long and 110 meters wide. Within the walls Robert had constructed the Salle de Roi, the meeting room for the Curia Regis, the assembly of nobles and for the royal council. To the west of this building he built his own residence, the chambre de Roi. Finally, he built a chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas.

Floor plan of the palace at the sane epoch, by

Eugene Viollet-le-Duc; Saint-Chapelle is in the center, the site of the modern Conciergerie below it

Further additions were made by Louis VI, with the help of his friend and ally, Suger, the Abbot of the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Louis VI finished the chapel of Saint Nicholas, demolished the old tower or donjon in the center, and built a massive new donjon, or tower, the Grosse Tour, 11.7 meters wide at the base, with walls three meters thick. This tower existed until 1776.

His son, Louis VII (1120-1180) enlarged the royal residence and added an oratory; the lower floor of the oratory later became the chapel of the present Conciergerie. The entrance to the palace at this time was on the eastern side, on the Cour du Mai, where a grand ceremonial stairway was constructed. The western point of the island was transformed into a walled garden and orchard.

Philip-Augustus

Philip-Augustus (1180-1223) modernized the royal administration, and placed the royal archives, the treasury and courts within Palais de la Cité, and thereafter the city functioned, except for brief periods, as the capital of the kingdom. In 1187 he welcomed the English king, Richard the Lion-Hearted, to his palace. The court records show the creation of a new official position, the Concierge, who was responsible for the administration of the lower and mid-level law courts within the Palace. The palace later took its name from this position. Philip also greatly improved the air and aroma around the Palace by having the muddy streets around the Palace paved with stone. These were the first paved streets in Paris.

Louis IX and Sainte-Chapelle

The grandson of Philip Augustus, Louis IX (1214-1270), later known as Saint Louis, built a new shrine within the palace walls to demonstrate that he was not just King of France, but also the leader of the Christian world. Between 1242 and 1248, on the site of the old chapel, he built Sainte-Chapelle to hold the sacred relics Louis had acquired in 1238 from the governor of Constantinople including the reputed crown of thorns and wood from the cross of the Crucifixion of Christ, The chapel had two levels; the lower level for ordinary servants of the king, and the upper level for the king and royal family. The upper chapel was connected directly to the King’s residence by a covered passage, called the Galerie Merciére. Only the King was allowed to touch the crown of thorns, which he took out each year on Good Friday.

Louis IX also created several new offices to manage the finances, administration and judicial system of his growing Kingdom. This new bureaucracy, housed within the Palace, eventually led to conflict between the royal government and the nobles, who had their own high court, the Parlement de Paris. To make room for his growing bureaucracy, and to create residences for the Chanoines or Canons, who managed the religious establishment, he had the southern wall of the Palace demolished and replaced with housing. On the north side of the palace, just outside the walls to the Tour Bonbec, he built a new ceremonial hall, the Salle sur l’eau.

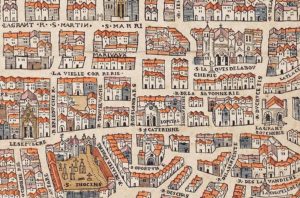

Philip IV Le Bel

King Philip IV (1285-1314) and his Chamberlain, Enguerrand de Marigny, reconstructed, enlarged and embellished the Palace. On the north side of the Palace, he expropriated land belonging to the Counts of Brittany and constructed new buildings for the Chambre des Enquetes, which supervised public administration; the Grand’Chambre, another high court; and two new towers, the Tour Cesar and the Tour d’Argent, as well as a gallery connecting the palace to the Tour Bombec. The royal offices took their names from the different chambers, or rooms, of the palace; the Chambre des Comptes, chamber of the accounts, was the treasury of the kingdom, and the courts were divided between the Chambre civile and the Chambre criminelle.

On the site of the old Salle de Roi he built a much larger and more richly decorated assembly hall, the Grand’Salle which had a double nave, each covered with a high arched wooden roof. A row of eight columns in the center of the hall supported the wooden framework of the roof. On each of the pillars, and on columns around the walls, were placed polychrome statues of the Kings of France. In the center of the hall was an enormous table made of black marble from Germany, used for banquets, the taking of oaths, meetings of military high courts, and other official functions. A fragment of the table still exists, and is on display in the Conciergerie. The Grand’Salle was used for royal banquets, judicial proceedings, and theatrical performances. At the west end of the island, where Place Dauphine is today, was a walled private garden, a bath house where the King could bathe in the water of the river, and a dock, from which the king could travel by boat to his other residences, the Louvre fortress on the right bank and the Tour de Nesle on the left bank.

The lower floor beneath the Grand’Salle contained the Salle des Gardes for the soldiers who protected the King, as well as the dining room for the household of the King, including officers, clerks, court officers and servants. High court officials had their own houses in the city, while lower officials and servants lived within the Palace. The household of the King at the time of Philip le Bel numbered about three hundred persons; counting the servants of the Queen and of the King’s children, the number grew to about six hundred.

Philip made several further major changes to the Palace. He reconstructed the south wall of the Palace, and moved the wall on the east side to enlarge the ceremonial courtyard, The new wall, more that of a palace than a fortress, had two large gates and echauguettes, or small elevated posts for watchmen at the angles of the wall. He restored the Salle d’Eau, extended the logos de Roi, or royal residence further south, built a new building for Chambre des comptes, or royal treasury, and enlarged the garden. The works were almost complete when the King died in 1314. Philip’s successors made a few further additions; Jean II le Bon (1319-1364) constructed new kitchens on two levels northwest of the Grand’Salle, and built a new square tower. Later, his son, Charles V (1338-1380) installed a clock in the tower, and it became known as the Tour de l’Horloge.

Palace of justice and prison (14th century)

The Hundred Years War between England and France changed the history and function of the Palace. King Jean Le Bon was taken hostage by the English. In 1358 the leader of the Paris merchants, Etienne Marcel, led an uprising against royal authority. His soldiers invaded the palace, and, in the presence of the King’s son, the future Charles V, they killed the King’s counselors, Jean de Conflans and Robert de Clermont. The rebellion was abandoned and Marcel was killed, but when Charles V took the throne in 1364, he decided to move his residence a safe distance from the center of the city. He built a new residence, the Hôtel Saint-Pol, in the Marais quarter, close to the safety of the Bastille fortress; and later the Louvre Palace and then the Tuileries Palace became the royal residences.

The Kings of France did not entirely abandon the Palace. They returned frequently for ceremonies in the Grand’Salle, receptions for foreign monarchs, to preside over sessions of the Parlement de Paris, and to display the sacred relics at Saint-Chapelle for the veneration of the court. Until the 16th century, some of the Kings made extended stays within the Palace. Nonetheless, the chief occupation of the Palace became the administration of the treasury and especially of royal justice. It became the headquarters of the Parlement of Paris, which was not a legislative body but a high court of the nobility. The Parlement registered all royal decrees, and was the court of appeals for the nobility from decisions of royal tribunals. It met in the Grand’Chambre, with the King presiding. The management of the Palace became the responsibility of the Concierge, a high court official named by the King. At one point in the 15th century, the title belonged to Isabeau of Bavaria, the wife of King Charles VI. The palace gradually took its name from this official, and was called the Conciergerie.

As early as the 14th century, the Palace was also used to confine important prisoners, since it was not necessary to transfer them from the city’s major prison at Châtelet for trial. Furthermore, the Palace had its own torture chambers, used to encourage the rapid confessions of prisoners. By the 15th century the Palace was one of the major prisons of Paris. The entrance of the prison was located on the main courtyard, the Cour du Mai, named for the tree that the clerks of the Palace traditionally placed there every spring. The prison cells were located in the lower floors of the Palace and in the towers, where the torture was also conducted. Prisoners were rarely kept there for a long time. As soon as judgement was given, they were taken briefly to the parvis in front of the Cathedral of Notre Dame to have their confession heard, then to their execution on the Place de Greve.

Notable prisoners held at the Palace before their executions included Enguerrand de Marigny, the chancellor of King Philip le Bel, who oversaw the construction of much of the Palace, accused of corruption by the King’s successor, Louis X; Gabriel the Count of Mongomery, whose lance fatally wounded Henry II during a tournament, who was later accused of advocating religious reforms and disobedience to King Charles IX; François Ravaillac, the assassin of Henry IV; Marie-Madeleine d’Aubray, the marquise of Brinvilliers, a famous poisoner; the bandit Cartouche; and Robert François Damien, a Palace servant who tried to kill Louis XV. Jeanne de Valois, the Countess de la Motte, the central figure in the notorious Affair of the Diamond Necklace, who plotted to defraud Marie Antoinette, was held there, whipped, branded with a V for Voleur (thief), then transferred to the Saltpétriére Prison for a life sentence, but escaped a few months later.

From the Renaissance to the Revolution

From the 14th through the 18th century, the Kings of France made many modifications to the palace, particularly to Sainte-Chapelle. in 1383, Charles VI replaced the spire of Sainte-Chapelle, and, at the end of the century, an oratory was built on the outside of the chapel against the south wall. From 1490 to 1495, Charles VIII installed a new rose window on the western facade of the chapel. In 1504, Louis XII added a monumental stairway on the south side of the palace, and constructed a new building for the Chambre des comptes, the royal treasury. In 1585, Henry III added a sundial to the wall of the clock tower, and began the construction of the Pont Neuf, a new bridge to connect the island to the left and right banks of the Seine. In 1607, Henry IV gave up the royal garden at the end of the island and had a new residential square, Place Dauphine, constructed on the site. In 1611, Louis XIII had the banks of the river around the island rebuilt of stone.

In 1618, a major fire destroyed the Grand’Salle. It was reconstructed following the same plan by Salomon de Brosse in 1622. In 1630 another fire destroyed the spire of Sainte-Chapelle, which was replaced in 1671. In 1671, King Louis XIV, always short of money for his grandiose projects, followed the earlier practice of Henry IV at Place Dauphine, and began dividing excess land around the palace into lots for new building. By the 18th century, the palace was completely surrounded by private houses and shops built right up against its walls.

Louis XIV arrives at the Palais de la Cité to preside over a session of the Parlement de Paris (1715)

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, the palace was struck by a series of natural catastrophes. The river Seine rose during the winter of 1689-1690, flooding the Palace and causing considerable damage, including the destruction of the stained glass windows on the lower level of Sainte-Chapelle. In 1737, a fire destroyed the Cour de Comptes. The reconstruction of the building was accomplished by Jacques Gabriel, the father of Ange-Jacques Gabriel, architect of the Place de la Concorde. An even more serious fire occurred in 1776, causing serious damage to the residence of the King, the Grosse Tour, and the buildings around the Cour de Mai. In the reconstruction, the old Treasury of Chartres, the Grosse Tour and the eastern wall of the palace were demolished. A new face, the present facade, was given to what became known as the Palace of Justice; a new gallery was built at Sainte-Chapelle; a new chapel was constructed inside the Conciergerie to replace the oratory from the 12th century, and many new prison cells were constructed, which were to play a notorious role in the French Revolution.

The Revolution and the Terror

The Conciergerie during the Revolution (1790)

In the turbulent years before the French Revolution, one important center of opposition to the authority of the King, the Parlement of Paris, was found within the Conciergerie. In May, 1788, he nobles, who met the Grand’Salle of the Conciergerie, refused to allow the King to launch an investigation of one of their members.

In July, 1789, after the storming of the Bastille, power passed to a new Constituent Assembly, which had little sympathy for the nobles of the Parlement of Paris. The Assembly put the Parlement on an indefinite vacation, and in 1790 the first elected mayor of Paris, Jean Sylvain Bailly, closed and sealed the offices of the Parlement.

The Revolution took a more radical turn in August 1792, when the first Paris Commune and the ’’Sans-culottes’’ seized the Tuileries Palace and arrested the King. In September, the ‘’sans-Culottes’’ massacred 1,300 prisoners in four days, including those held in the Conciergerie, who were killed in the ‘’Cour des Femmes’’, the yard where women prisoners were allowed to exercise.

The new revolutionary government of the Convention was soon divided into two factions, the more moderate Girondins and the more radical Montagnards, led by Robespierre. On March 10, 1793, Convention, over the opposition of the Girondins, ordered the creation of a Revolutionary Tribunal, with its headquarters in the Conciergerie. The tribunal met in the ‘’Grand’Salle’’, where the Parlement of Paris had held its meetings, which was renamed the ‘’Salle de la Liberte’’. It was headed by Fouquier-Tinville, a former state prosecutor, aided by a jury of twelve members. In the Convention, Robespierre had a new Law on Suspects passed, which deprived prisoners before the Tribunal of most of their rights. There was no appeal to decisions of the tribunal, and sentences of death were carried out the same day.

Among the first to be tried was Marie Antoinette, who had been held a prisoner for two and half months since the trial and execution of her husband, Louis XVI. She was tried on October 16, 1793 and executed on the same day. On October 24, twenty Girondin members of the Convention were put on trial for conspiring against the unity of the new Republic, and immediately executed. Others brought before the Tribunal and executed included Philippe Egalite, a cousin of the King, who had voted for the King’s execution (November 6); Bailly, the first elected Mayor of Paris; (November 11), and Madame du Barry, a favorite of the King’s father, Louis XV (December 8).

Prisoners rarely spent a long time in the Conciergerie; most were brought there a few days or at the most a few weeks before their trial. There were as many as six hundred prisoners there at a time; a small number of wealthy prisoners were given their own cells, but most were crowded into large common cells, with straw on the floor. At dawn the cell doors were opened the prisoners were allowed to exercise in the courtyard or in the corridors. Women prisoners went to a separate courtyard with a fountain, where they could wash their clothes. Prisoners gathered at the foot of Bonbec Tower each evening to hearP the guards read the names of those who would be brought before the Tribunal the next day. Those whose names were announced were traditionally given a meager banquet with other prisoners that night.

Soon the Tribunal tried anyone who opposed Robespierre. Jacques Hébert, Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and many others were brought before the Tribunal, judged and executed. many opponents of Robespierre were arrested that the Tribunal began trying them in groups. By July 1794 an average of thirty-eight persons a day were judged and guillotined. Gradually, however, opposition grew against Robespierre, who was accused of wishing to be a dictator. He was arrested on July 28, 1794, after trying unsuccessfully to shoot himself. He was taken to the infirmary of the Conciergerie, then, a few hours later, tried by the Tribunal, and executed on the Place de la Revolution. The chief of the Tribunal, Fouquier-Tinville, was arrested, and after nine months in prison in the Conciergerie, was also executed on May 9, 1795. The Revolutionary Tribunal was abolished on May 7, 1795, after having put to death 2,780 persons in 718 days.

The Palace in the 19th century

Following the Revolution, the Palace became the headquarters of the judicial system of France, but also continued its vocation as a prison. During the Consulate of Napoleon Bonapartre, the rebel Georges Cadoudal was imprisoned there until his execution in 1804. After Napoleon’s downfall, one of his most famous generals, Marshal Michel Ney, were imprisoned there before his execution in 1815, as was Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the future Napoleon III, after his failed attempt to overthrow King Louis Philippe. The anarchists Giuseppe Fieschi and Felice Orsini, who tried respectively to kill Louis-Philippe and Napoleon III, were both imprisoned there, as was another famous anarchist, Ravachol, who was executed in 1892.

During the Revolution, Sainte-Chapelle had been turned into a storage vault for legal documents, and half of the stained glass removed. Between 1837 and 1863, a major campaign was begun to restore the chapel to its medieval splendor. At the same time, the Conciergerie and Palace of Justice underwent major changes. Between 1812 and 1819, Antoine-Marie Peyrie restored the vaulted ceiling of the old Medieval hall of the men-at-arms, and also, at the request of the restored King Louis XVIII, built an expiatory chapel where the cell of Marie-Antoinette had been. Between 1820 and 1828, he built a new facade for the Conciergerie along the Seine between the Tour de l’Horloge and the Tour Bonbec. In 1836, a new entrance was to the Conciergerie was made between the Tour d’Argent and the Tour César

The ruins of the Palace of Justice after the Paris Commune (1871)

Another large building project by architects Joseph Louis Duc and Etienne Theodore Dommey by between 1847 and 1871 greatly enlarged the Palais de Justice. They built a new facade along the Boulevard du Palais, constructed a building for the Correctional Police, reconstructed the roof of the Salle des pas-perdus, and restored the Tour de l’Horloge. They also demolished some of the last vestiges of the old palace, including what remained of the Logis du Roi and the Salle sur L’eau’, and began construction of a new building for the Cour de cassation.

In May 1871, the Palace was struck by another catastrophe; during the last days of the Paris Commune, the soldiers of the Commune set fire to important government buildings, including the Tuileries Palace, the Hotel de Ville and the new Palais de Justice. The new Palais was largely destroyed. A major restoration project by architect Viollet Le Duc over twenty years rebuilt it. Duc also finished the Harlay facade, while architect Honore Daumét completed the building of the Court of Appeals. The last building of the Palace of Justice, the Tribunal Correctionelle on the corner of the Quai d’Orfevres, was completed between 1904 and 1914.

The Conciergerie was declared a national historical monument in 1862, and some rooms were opened to the public in 1914. It continued to function as a prison until 1934.

Vestiges of the Medieval Palace

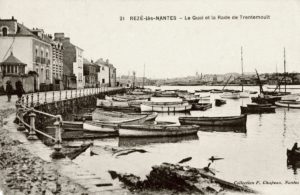

The towers

The Bonbec Tower (1226-1270) held the torture chamber of the palace prison

The four towers (Horloge (L), César, Argent, Bonbec (R))

The Tour de l’Horloge, or clock tower (14th century)

The clock on the Tour de l’Horloge (14th century)

The four towers along the Seine date back to the Middle Ages, while the facade is more modern, dating to the early 19th century. The tower on the far right, the Tour Bonbec, is the oldest, built between 1226 and 1270 during the reign of Louis IX, or Saint Louis. It is distinguished by the crenolation at the top of the tower. It originally was a story shorter than the other towers, but was raised to match their height in the renovation of the 19th century. The tower served as the primary torture chamber during the Middle Ages; it was said that prisoners tortured would sing like birds, with a “bon bec’, or beak open wide.

The two towers in the center, the Tour de César and the Tour d’Argent were built in the 14th century. Each has four levels. Starting in the 15th century, the top levels held the offices of the clerks of the court, both criminal and civil. The lower floors contained jail cells.

The tallest tower, the Tour de l’Horloge, was constructed by Jean le Bon in 1350, and modified several times over the centuries. The first public clock in Paris, made by Henri d’Vic, was added by Charles V in 1370. The sculptural decoration around the clock, featuring allegorical figures of The Law and Justice, was added in 1585 century by Henry III. They were smashed during the Revolution but later restored. At the top of the tower was a bell, which was rung to announce important events in the life of the royal family, and was also rung to signal the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. The original bell was removed and melted down during the Revolution.

The facades were constructed in the 19th century in the neogothic and neoclassic style, during the restoration and rebuilding of the Palace. The facade to the east, or left, is by Antoine-Marie Peyre, and that to the west, or right, by Joseph Louis Duc and Étienne Theodore Dommey.

The Medieval halls

The Salle des gens d’armes, below the now vanished Medieval Grand’Salle.

The Salle des gardes, beneath the former Grand’Chambre

Stairways in the Salle des gardes to the Argent and Cesar towers

The two halls in the lower part of the Conciergerie, the Salle des Gardes (Hall of the Guards) and the Salle des Gens d’armes (Hall of the Men at Arms), along with the kitchens, are the only surviving rooms of the original Capetian palace. When they were built, the two halls were at street level, but over the centuries, as the island was built up to prevent floods, they were below the street. The Salles des Gardes was built at the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, as the ground floor of the Grand’Chambre, where the King conducted judicial hearings, and where, during the Revolution, the Revolutionary Tribunal met. It was connected with the hall above by a stairway in the southwest part of the hall, and by a second stairway in a tower which was demolished in the 19th century. It is one of the finest examples of medieval architecture in Paris. The hall is 22.8 meters long, 11.8 meters wide, and 6.9 meters high. The massive columns have decorative sculpture of combat of animals and narrative scenes. Two stairways on the north side of the hall lead up to the towers of Argent and Cesar where prison cells were located. During the Revolution, the apartment of the chief prosecutor of the Terror, Fouquier-Tinville, was on the upper floor, and his office was in the Tower of Cesar. The Salle des Gardes was filled with prison cells until the mid-19th century, when the hall was restored to its original appearance.

The Salle des Gens d’armes was the ground floor below the magnificent Grand’Salle, where the Kings of France held banquets to welcome royal guests, and to celebrate special events, such as the visit of German Emperor Charles IV in 1378, hosted by Charles V shortly before he moved out of the Palace, and the marriage of Francis II with Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots. The hall itself, with a high double-vaulted wooden roof, burned several times, most recently in fires started by the Paris Commune in May 1871. It was replaced by a new grand hall, the Salle des Pas Perdu , of the Palace of Justice. During the Middle Ages the lower floor was used largely as a restaurant and holding area for the large staff of the Royal household; it could serve as many as two thousand persons. A large stairway, now walled off, connected the lower floor with the Grand’Salle. The Salle is 63.3 meters long, 27.4 meters wide, and 8.5 meters high. Beginning in the 15th century the hall was divided into smaller rooms and prison cells.

The hall underwent many changes and restorations over the centuries. After a fire destroyed most of the upper hall in 1618, the architect Salomon de Brosse built a new hall, but made the error of not placing the new columns over the original columns in the lower level. This led in the 19th century to the collapse of part of the roof of the lower hall, which was rebuilt with additional columns. In the 19th century windows were also added on the north side looking out at the courtyard. The circular stairway in the northeast corner of the Salle, built in the medieval style, was constructed in the 19th century during the reign of Napoleon III, who had briefly been held a prisoner himself in the building.

Sainte-Chapelle

Main article: Saint Chapelle

The windows of the upper chapel

The ceiling of the lower chapel

Sainte Chapelle was constructed by King Lous IX, later known as Saint Louis, between 1241 and 1248 to keep the holy relics of the Crucifixion of Christ obtained by Louis, including what was believed to be the Crown of Thorns. The lower level of the chapel served as the parish church for the residents of the Palace. The upper level was used only by the King and royal family. The stained glass windows of the upper chapel, about half of them original, are one of the most important monuments of Medieval art in Paris. The chapel was turned into a storage depot for court documents from the Palace of Justice after the Revolution, but was carefully restored during the 19th century.

The 18th century prison

The Chapel of the Girondins, converted to prison cells

The prison quarter of the Palace visible today dates to the late 18th century. After a fire in 1776, Lous XVI had a section of Conciergerie prison rebuilt; During the French Revolution it served as the principal prison for political prisoners, including Marie Antoinette, before their trials and execution r. The prison was extensively rebuilt in the 19th century, and many famous rooms, such as the original cell of Marie Antoinette, disappeared. However, part of the prison was restored for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution in 1989, and can be seen by visitors.

The Rue de Paris was a section of the Salle des gardes which was separated by a grill from the rest of the hall during the 15th century. During the Revolution it was used as a common cell for prisoners when the all the other cells were full. It took its name from “Monsieur Paris”, the nickname for the executioner.

The Chapel of the Girondins is one chamber that has changed little since the Revolution. It was constructed after the 1776 fire on the site of medieval oratory of the Palace. In 1793 and 1794, when the prison was overcrowded, it was converted to prison cells. It took its name from the Girondins, a Revolutionary faction of deputies who opposed the more Montagnards of Robespierre. The Deputies were arrested, and held a last “banquet” in the chapel the night before their execution.

The Cour des Femmes was the courtyard where women prisoners, including Marie-Antoinette, were allowed to walk, to wash their clothing in the fountain, or to eat at an outdoor table. The courtyard is little changed from the time of the Revolution.

The cell where Marie-Antoinette passed two and half months before her trial and execution was turned into an expiatory chapel by King Louis XVIII after the restoration of the monarchy. The chapel occupies both the space of her original cell and the infirmary of the prison, where Robespierre was held after his suicide attempt and before his trial and execution. Though not in the same location, the cell faithfully copies the arrangement and details of the original cell, including the 24-hour surveillance of the Queen by a soldier.

References

Notes and citatation

- Delon 2000.

- Fierro 1996, p. 22.

- Delon 2000, pp. 6-7.

- Delon 2000, pp. 10.

- Bove & Gauvard 2014, pp. 77-82.

- Delon 2000, pp. 12-13.

- Sarmant 2012, pp. 43-44.

- Delon 2000, p. 14.

- Delon 2000, p. 15.

- Delon 200, pp. 16-20.

- Delon 200, pp. 19-20.

- Delon 2000, pp. 20-21.

- Delon 2000, p. 30.

- Delon 2000, p. 30-32.

- Delon 2000, p. 32.

- Delon 2000, p. 34.

- Delon 2000, pp. 35–37.

- Delon 2000, p. 41.

- Delon 2000, pp. 45-50.

- Delon 2000, p. 58.

- Delon 2000, p. 63.

Bibliography

Bove, Boris; Gauvard, Claude (2014). Le Paris du Moyen Age (in French). Paris: Belin. ISBN 978-2-7011-8327-5.

Combeau, Yvan (2013). Histoire de Paris. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-060852-3.

De Finance, Laurence (2012). La Sainte-Chapelle – Palais de la Cité. Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN 978-2-7577-0246-8.

Delon, Monique (2000). La Conciergerie – Palais de la Cité. Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN 978-2-85822-298-8.

Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221–07862-4.

Hillairet, Jacques (1978). Connaaissance du Vieux Paris. Paris: Editions Princesse. ISBN 2-85961-019-7.

Héron de Villefosse, René (1959). HIstoire de Paris. Bernard Grasset.

Meunier, Florian (2014). Le Paris du moyen âge. Paris: Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6217-0.

Piat, Christine (2004). France Médiéval. Monum Éditions de Patrimoine. ISBN 2-74-241394-4.

Sarmant, Thierry (2012). Histoire de Paris: Politique, urbanisme, civilisation. Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-755-803303.

Schmidt, Joel (2009). Lutece- Paris, des origines a Clovis. Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03015-5.

Dictionnaire Historique de Paris. Le Livre de Poche. 2013. ISBN 978-2-253-13140-3.