Amboise is a commune in the Indre-et-Loire department in central France. It lies on the banks of the Loire River, 27 kilometres east of Tours. The city is famous for the Clos Lucé manor house where Leonardo da Vinci lived (and ultimately died) at the invitation of King Francis I of France whose Château d’Amboise which dominates the town, is located just 500 metres away.

The following excerpt is from the Château d’Amboise official website

The château through the centuries

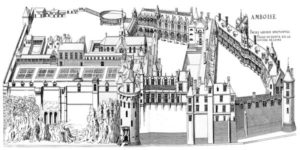

The Royal Château of Amboise site has undergone huge transformations through the centuries. Recently collected scientific data have enabled recreation of the château in all its forms, from the Middle Ages to today.

ORIGINS TO 1431

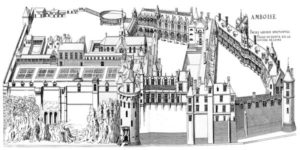

View at the time of the lords of Amboise before 1431

Since Neolithic times, the Châteliers promontory has been an ideal observation post for the confluence of the Loire and one of its tributaries, the Amasse. Towering nearly 40 metres high, it offered an exceptional natural defence. The town became the main city of the Turones, a Celtic people who gave their name to the future province of Touraine. The site has been fortified since this era.

Roman legions also occupied this fortified site. Local chronicles report that Julius Caesar (100 BC- 44 BC) himself was rather taken with the Amboise oppidum.

However, the site made a significant entrance into the history books with the meeting of Clovis (around 466- 481- 511), king of the Francs, and Alaric (?- 484-507), king of the Visigoths. After the troubled period of the Norman invasions, Amboise incorporated the domain of the Counts of Anjou, then the domain of the house of Amboise-Chaumont. In 1214, Touraine was occupied by Philippe Auguste (1165- 1180- 1223), king of France. The Amboise-Chaumont family became his vassals. However, in 1431, Louis of Amboise (1392-1469) was condemned to death for plotting against La Trémoille (1384-1446), the favourite of King Charles VII (1403- 1422-1461). Finally pardoned, Louis of Amboise nevertheless had to renounce the Château of Amboise, which was confiscated by the Crown.

Thus began the more château’s more luxurious days, notably during the reigns of Louis XI, Charles VIII and François Ier, the kings of France who made Amboise shine with a particularly rich court life.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the court of France was based in Amboise

View of the castle during the reign of Louis XI

The arrival in Bourges of Charles VII (1403- 1422-1461) and his wife Marie of Anjou (1404- 1463) marked the beginning of the French kings’ residence in the Loire Valley. However, the latter preferred the Châteaux of Loches and Chinon to the fortified Château of Amboise.

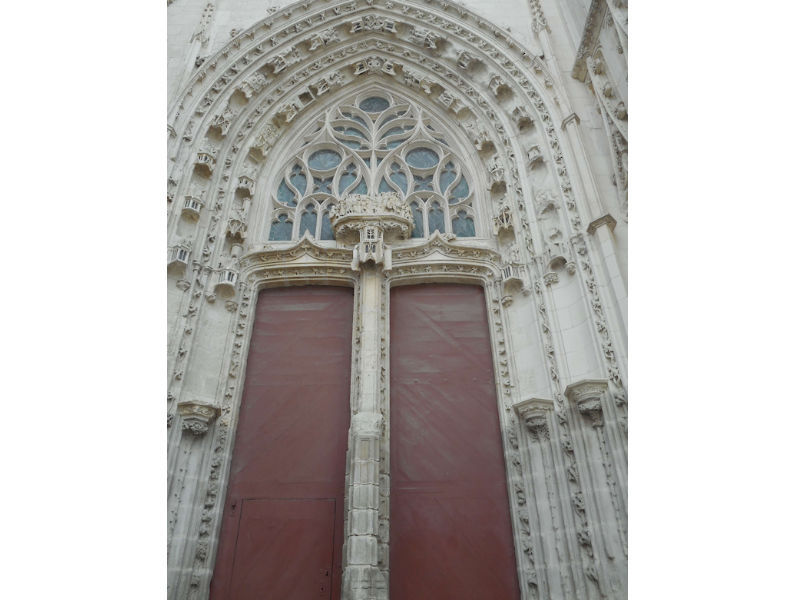

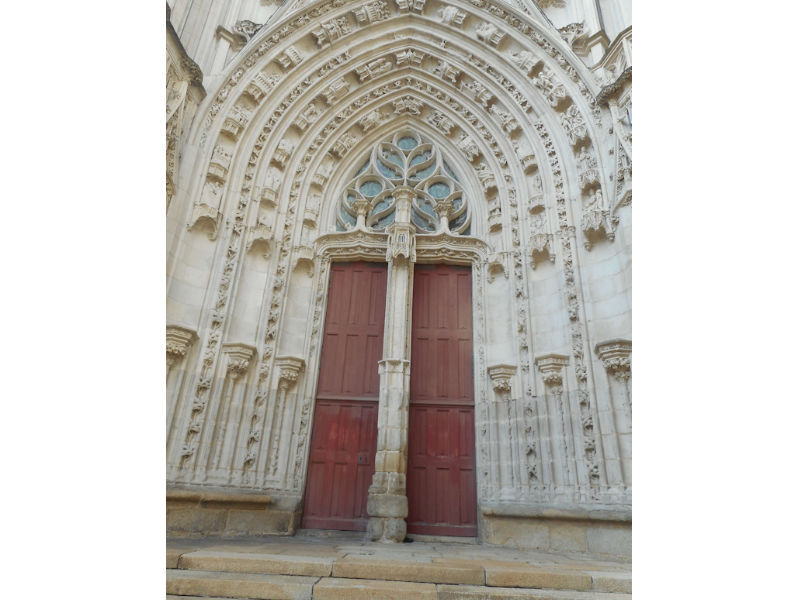

As for their son, Louis XI (1423- 1461-1483), he resided in his château at Plessis-Lès-Tours (in La Riche). However, he chose Amboise as the residence for the queen, Charlotte of Savoie (1441/ 1461/1483), and the heir apparent – the future Charles VIII (1470- 1483-1498) – born in Amboise in 1470. He had a new loggia and an oratory built, the latter resting against the southern surrounding wall, on the site of the future St. Hubert Chapel.

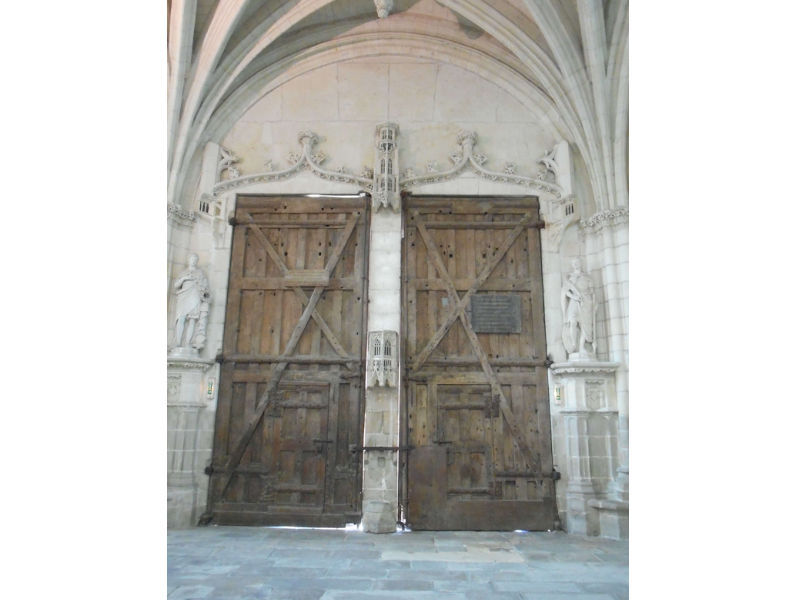

Charles VIII (1470- 1483-1498) and his wife, Anne of Brittany (1477/ 1491-1498/1499-1514), left a lasting mark on Amboise. The king’s ongoing attachment for the château of his childhood certainly influenced his desire to transform the former medieval stronghold into a sumptuous Gothic palace. Charles VIII was also the château’s great architect, since he ordered the successive construction of the two ceremonial loggias and a chapel on the site of the oratory built by his father. In addition, he ordered the construction of the two exceptionally large cavalry towers (a third was never finished). These enabled horses and carriages to go back and forth between the town and the château’s terraces 40 metres above it. These exceptionally extensive building works were funded by the royal treasury and continued despite the military campaigns on the Italian peninsula.

Innovative techniques were even used to heat the stones and to stop them freezing in winter so that work could continue. The king called upon French masons, Flemish sculptors, and then on his return from Italy, Italian artisans: carpenters, gardeners and architects. At that time, the château had 220 rooms.

François 1er en 1515 par Jean Clouet

The king’s emblems and monograms – the flaming sword – and queen Anne of Brittany’s ermine (1477/ 1491-1498/ 1499-1514), visible in the château’s rooms bear witness to the royal couple’s presence. However, the premature death of Charles VIII, at 28 years of age, prevented him from seeing his great project completed.

Since Charles VIII died without a male heir, his cousin, the Duke of Orléans, succeeded him under the name of Louis XII (1462- 1498-1515). In order to keep the Duchy of Brittany in the French fold, Louis XII had to marry the dead king’s widow. Thus, Anne of Brittany (1477/1491-1498/ 1499-1514) became the only woman in French history to hold the title of queen twice.

The new king mainly lived in his stronghold in Blois, while his young cousin and heir apparent, François of Valois-Angoulême, the future François Ier, was educated at Amboise.

Louis XII continued the building projects initiated by his predecessor and completed the Heurtault Tower in the perpendicular wing of his predecessor’s Loggia.

After his childhood at the château and his accession, on 1st January 1515, François Ier (1494- 1515-1547) left France for Italy and won the Battle of Marignan in September of that year. However, he did not forget Amboise, which he embellished. He enhanced the château’s Louis XII wing and decorated the dormer windows in the “Italian style”.

François Ier’s fascination for literature and the arts made him a great Renaissance patron king. He invited numerous Italian artists to Amboise, including Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) who resided there from 1516 to 1519.

The Castle of Amboise by Léonard de Vinci 1517

Henri II (1519- 1547- 1559), François Ier’s son, was behind the construction of a building parallel to the Louis XII wing (no longer in existence) in which he created apartments for the French royal children. After his death, his wife Catherine de Medici (1519-1589) assumed the kingdom’s regency.

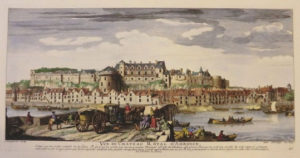

View of the castle in the time of Catherine de Medici

The three sons of Henri II and Catherine de Medici, François II (1544- 1559-1560), Charles IX (1550- 1560-1574) and Henri III (1551-1 1574-1589) successively held the French throne.

Under François II’s short reign, Amboise was the backdrop for the Amboise conspiracy. After this tragic episode, Catherine de Medici had the château’s east defences reinforced and gave orders for the construction of a bastion.

Then, under Charles IX and Henri III, royal visits to the Château became less frequent. As such, Amboise progressively stopped being the seat of the French court.

17th and 18th centuries: a citadel, residence of the French sovereigns

At the end of the 16th century, Amboise retained its function as a stronghold because of its strategic location, but became a residence for French sovereigns who stayed there during their travels around the kingdom. For example, Henri IV (1553- 1589- 1610), Louis XIII (1601- 1610-1643), Louis XIV (1638- 1643-1715) and Philippe Duke of Anjou (1683- 1700/1724-1746), his grandson, the future Philippe V of Spain.

In 1620, Louis XIII ordered the construction of new defences. However, due to lack of maintenance the château began to fall into disrepair. The main parts of the loggia inside the western part of the château (between the St. Hubert Chapel and the Charles VIII Loggia) were demolished between 1627 and 1660.

Amboise was also used as a prison. Famous prisoners were held there, for example Nicolas Fouquet (1615-1680), Louis XIV’s superintendent of finances, who was disgraced in 1661. He was accompanied to Amboise by the famous captain of the Musketeers, d’Artagnan (around 1615-1673).

Amboise finally awoke from its slumber in the 18th century thanks to Étienne-François, Duke of Choiseul (1719-1785), a powerful minister of Louis XV (1710- 1715-1774).

He became the property’s owner in 1763, at the same time as he built a sumptuous château in the style of the era, nearby in the domain of Chanteloup. He preferred living in the latter to the citadel of Amboise, where he installed workshops.

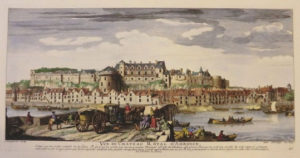

Engraving by Rigaud, The Château in 1730

On the death of Choiseul, the Crown bought his immense estate. Then in 1786, it was given to Louis-Jean-Marie de Bourbon, Duke of Penthièvre (1725-1793), legitimate grandson of Louis XIV. From 1789, he refurbished the living areas. He went ahead with the destruction of the Great Hall’s columns and partitions. He created a panoramic dining room in the Minimes Tower. He ordered works in the gardens, during which the lime trees were planted in zigzags on the North terrace, and created an English-style park. On the fortress’s western corner, he built a Chinese-style pagoda on the Garçonnet tower.

In 1789, there was a fire in the Loggia of the Seven Virtues

The French Revolution definitively changed the Château’s destiny. In 1793, the authorities confiscated the Château and its contents in order to turn it into a detention centre and a barracks for veterans from campaigns led by the revolutionary armies. During this dismantling, essential elements of the Château’s decoration disappeared: panelling, fireplaces, statues, paintings, ironwork, woodwork, etc… After a fleeting hope that they might recover their belongings, the duke of Penthièvre’s heir, Louise-Marie-Adelaide, Duchess of Orléans, was exiled following the Coup d’État of 18 Fructidor in Year V (4th September 1797) due to the decree that obliged the Bourbons to leave France.

19th and 20th centuries: abuses and the historic monument’s restoration

Painting by Gustave Noël. The Château of Amboise in the 19th century

The Consulate (1799-1804) and the Empire (1804-1814/1815) opened a new chapter in the Château’s life. In 1803, Amboise was given to Senator Roger Ducos (1747-1816), a former member of the Directory. The First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte (future Napoléon Ier) (1769-1799/ 1804-1814-1815-1821) wished to thank the Senator for his help in seizing power. To ‘renovate the Château’, from 1806, the Senator ordered the destruction of the ‘useless or ruined’ buildings (the Loggia of the Seven Virtues and neighbouring buildings). Most notably, he destroyed the Henri II wing and the St. Florentin Collegiate Church (an 11th century building) and the canon’s house. The garden was also redone. All the works were completed in 1811.

In 1814, during the first Restoration, the Château was given back to the Duke of Penthièvre’s heir, Louise-Marie-Adelaide de Bourbon, Duchess of Orléans (1753-1821), returned from her Spanish exile. After having temporarily – during The Hundred Days – returned to its fortress/prison role, Amboise was definitively returned to the Orléans family in 1815.

Bust of Louis-Philippe

The chateau in the time of Louis-Philippe

On her death, the duchess passed on the domain of Amboise to her son Louis-Philippe (1773- 1830/1848-1850), future king of the French. He undertook renovations to transform the château into a ‘holiday’ destination. These works were entrusted to the renowned architect Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine (1762-1853) and his student, Pierre-Bernard Lefranc (1795-1856). King Louis-Philippe Ier, an ardent defender of French heritage, supported the classification of monuments that were emblematic of the nation’s history, and Amboise, classified in 1840, was one of the top ranking.

The 1848 Revolution led to the exile of Louis-Philippe Ier and the château was sequestered. Once more, it became a detention centre for a prisoner of note, Emir Abd el-Kader (1808-1883), the deposed leader of the Algerian uprising, who was incarcerated at Amboise with his retinue from November 1848.

The promise made to the Emir during his surrender to transfer him to an Islamic country, was only honoured four years later, by the Prince-President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (1808-1848/1852-1873), who came to inform him of his liberation in Amboise in October 1852.

The Emir left France for Bursa, Constantinople (Turkey) then Damascus (Syria). However, he left behind sincere friendships formed with Amboise residents and the memory of the 25 members of his retinue who died and were buried at the Château. The residents of Amboise thus contributed to the building of a mausoleum on one of the château’s terraces in 1853 (the ‘Garden of the Orient’, created by Rachid Koraïchi in 2005, is located on the same spot as the graves and mausoleum).

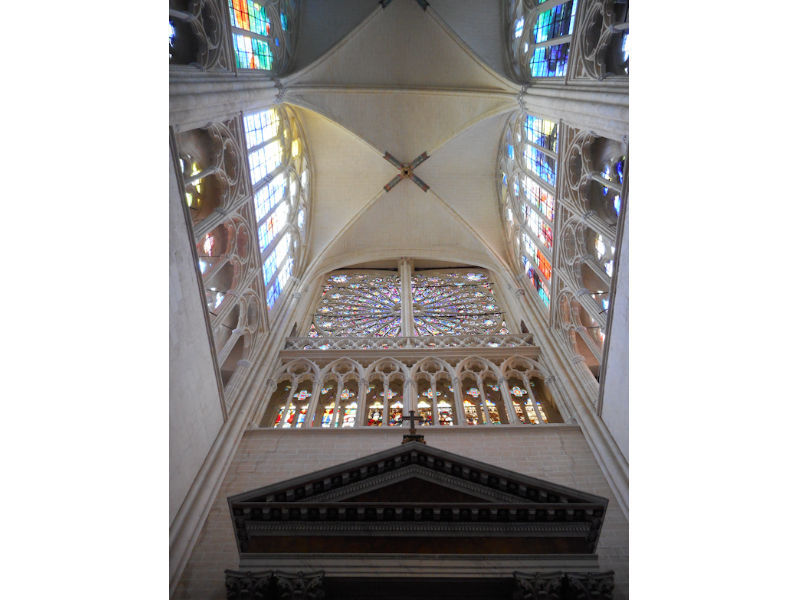

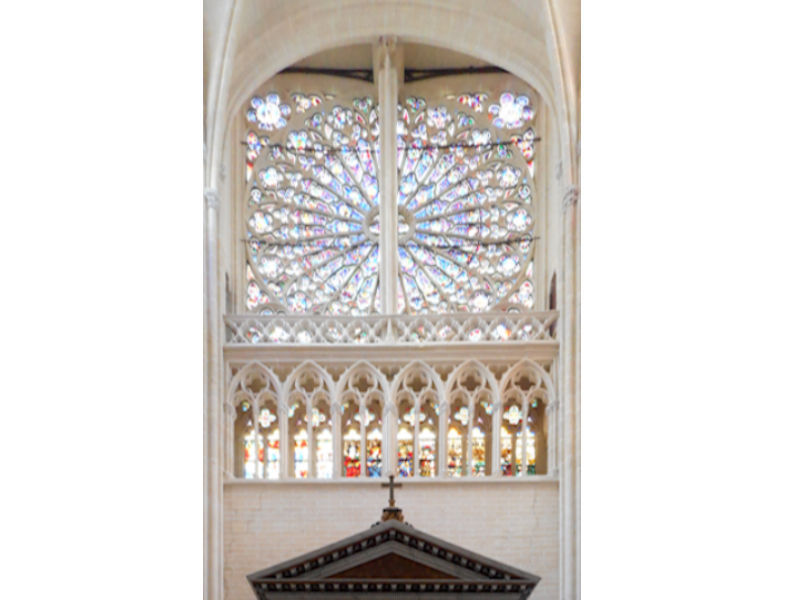

The fall of the Second Empire (1852-1870) and the advent of the 3rd Republic (1870-1940) marked the domain’s return to the Orléans family. A vast restoration programme began, on the initiative of Philippe (1838-1894), Count of Paris and grandson of Louis Philippe Ier. Since Amboise was listed as an historic monument, the State appointed an architect to lead the works. The architect in question, Victor-Marie-Charles Ruprich-Robert (1820-1887) and his son Gabriel after him, were both inspectors of historic monuments. They achieved remarkable restoration work on the St. Hubert Chapel, Charles VIII Loggia and the Minimes Tower (1874-1879), then the Renaissance wing (1896- 1897) and the Heurtault tower (1906).

The Duke of Aumale (1822-1897) commissioned the works. He died three years later and in 1901 the château, which already housed a hospice, was transformed according to his wishes into a clinic for former staff from his family’s household. The Château of Amboise was included in the ‘Société Civile du domaine de Dreux’ (Dreux Domain Civil Heritage Society), created in 1886 to manage the House of France’s historical heritage.

The final tragic episode for the Château and the town of Amboise occurred during the Second World War. From 4th September 1939, the château was requisitioned. Until 22nd May 1940, tourists were still able to visit the chapel and the Heurtault Tower’s rampart walkway.

In June 1940, the French army was routed and progressively withdrew south of the Loire. From 4th to 15th June 1940, the château’s royal loggia was thus the temporary HQ of the Air Ministry, which then fell back to Bordeaux

On 18th and 19th June 1940, a Senegalese infantry regiment resisted, with remarkable bravery, the German troops’ entrance to Amboise. There was considerable damage (about a hundred shells fell on the château) affecting the Chapel, and the Garçonnet and Minimes Towers. After its evacuation, the château suffered for 15 days from the uncontrolled influx of refugees and German troops. Then, it was used by the occupying troops as an arms depot and a post for aerial communications and detection.

In July 1944, the château was bombed by the Allies, which damaged the loggia façades and the St Hubert Chapel’s stained-glass windows and roof. On 1st August 1944, the last German army units left the château.

The inventory of the damage was carried out a few days later. The State assisted with the restoration campaign that began in 1952.

In 1974, the ‘Société Civile du Domaine de Dreux’ (Dreux Domain Civil Heritage Society) was transformed into the Fondation Saint-Louis, thanks to the development of legislation concerning management of cultural assets. As owners of the property, the Foundation launched a significant programme to restore and add value to the monument.

The chateau today

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

Google Maps – Amboise