![Le baptême de Clovis par saint Remi avec le miracle de la Sainte Ampoule (détail). Plaque de reliure en ivoire, Reims, dernier quart du IXe siècle. Amiens, musée de Picardie. Cette plaque servit sans doute à orner la reliure d'un manuscrit de la vie de saint Remi[1].](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/Saint_Remy_baptise_Clovis_d%C3%A9tail.jpg/220px-Saint_Remy_baptise_Clovis_d%C3%A9tail.jpg) Le baptême de Clovis par saint Remi avec le miracle de la Sainte Ampoule (détail). Plaque de reliure en ivoire, Reims, dernier quart du IXe siècle. Amiens, musée de Picardie. Cette plaque servit sans doute à orner la reliure d’un manuscrit de la vie de saint Remi1. |

|

| Titre | |

|---|---|

| Roi des Francs | |

| 481/482 – | |

| Prédécesseur | Childéric Ier |

| Successeur | Thierry Ier (roi de Reims) Clodomir (roi d’Orléans) Childebert Ier (roi de Paris) Clotaire Ier (roi de Soissons) |

| Biographie | |

| Titre complet | Roi des Francs |

| Dynastie | Mérovingiens |

| Date de naissance | vers 466 |

| Date de décès | 2 |

| Lieu de décès | Paris |

| Père | Childéric Ier |

| Mère | Basine de Thuringe |

| Conjoint | 1) Evochilde3,4 princesse franque 2) Clotilde |

| Enfants | Thierry Ier, Ingomer Clodomir, Childebert Ier Clotaire Ier, Clotilde |

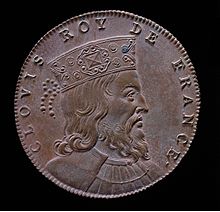

Clovis I , in Latin Chlodovechus , the only documented contemporary form attested, perhaps in reconstituted Francs * Hlodowig 5 , Note 1 (pronounced probably [xlod (o) wɪk] or [xlod (o) wɪç]), born around 466 and died in Paris on , is king of the Salian Franks , then king of all the Franks from 481 to 511 .

Coming from the Merovingian dynasty, he is the son of Childeric I , king of the Salian Francs of Tournai (Belgium), and Queen Basine of Thuringia . Brilliant military leader, he greatly increases the territory of the small kingdom of the Salian Franks which he inherited on the death of his father to unify a large part of the Frankish kingdoms, repel Alamans and Burgundians and annex the territories of the Visigoths in southern Gaul.

The reign of Clovis is best known from the description made by Gregory of Tours , a Gallo-Roman bishop whose history of the Franks is rich in teachings but whose aim is essentially edifying is accompanied by a lack of precision and historical coherence. The elements of Clovis’ life are not known with certainty and their “dressing” is most often suspect 6 .

Clovis is considered in historiography as one of the most important personages in the history of France ; the republican tradition recognizes in him the first king of what became France , and the royal tradition sees in him the first Christian king of the kingdom of the Franks Note 2 .

Summary

- 1 Primary sources

- 2 Gaul in the 5th century

- 3 Biography of Clovis

- 4 General aspects of the reign

- 5 Clovis representations in history, literature and art

- 6 Bibliography

- 7 Notes and references

- 8 See also

Primary sources

The History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours

The chronology of the reign of Clovis is very poorly known. Most of what we know comes from the story written at the end of the sixth century by Bishop Gregory of Tours , born nearly thirty years after the death of Clovis. This story is in fifteen short chapters Note 3 of Book II of his History of the Franks .

It has long been thought that this text was more about hagiography than about history . Thus, his narrative of the events follows a division into five-year slices, perhaps a reminiscence of quinquennalia or Roman lustra : war against Syagrius after five years of rule, fifteen for the war against the Alamans , war against the Visigoths five years before his death ; in all, a reign of thirty years after an advent at the age of fifteen. This information could be dismissed as legendary, but no study has ever fundamentally questioned these indications, which, in all likelihood, are slightly simplified, but remain valid “almost”.

The only date fixed by other sources than Gregory is that of his death, in 511 , which would date its advent of about 481 , perhaps 482 .

According to the historian Bruno Dumézil , some clarifications have recently been made thanks to the crossing of other documentary sources, without however contradicting the main elements of the history transmitted by Gregory 7 .

Other sources

Three sources prior to that of Gregory of Tours describe the political situation of northern Gaul 8 at that time. This is the Chronicle of Hydace , Bishop of Chaves in Gallaecia 9 ; a Gallo-Roman chronicle of the fifth century , the Chronica Gallica of 452 (continued by the Chronicica Gallica of 511 ); and the Chronicle of Marius , bishop of Avenches 10 .

Gaul in the fifth century

Evangelization in the Lower Empire

If the Christians of the first centuries venture to the evangelization of the empire, Christianity officially imposes itself only progressively from the IV E century, of the reign of Constantine I which converts to Christianity 12 , until to the reign of Emperor Theodosius I , who established Christianity as a state religion in 381 with the Thessalonian edict . Until then, and despite various edicts of religious tolerance, persecutions have prevented Christians from clearly defining a coherent doctrine; It is thus that the Emperor Constantine I organizes a council at Nicaea in 325 , to allow a theological and dogmatic harmonization. The result is dissension linked to the Trinitarian debate that favors two different concepts: the conciliar church preaches equality between the Father , the Son and the Holy Spirit ; Arianism , considered heretical by the conciliar, advocates the inferiority of the Son, considered a creature of God, 13 in relation to the Father 14 . By denying the divine nature of Christ and reducing him to a creature state, the Arians make the Messiah a being endowed with extraordinary powers but who is neither a man nor God.

Religions in Gaul in the fifth century

The great invasions and the fall of the Roman Empire allowed the durable installation of barbarian kingdoms in the empire and especially in Gaul . The barbarians , generally of Germanic origin, remained pagan because of their weak romanization. Apart from the short side of the Roman occupation of Germany under Augustus 9 BC. BC at 12 , the empire has only two provinces in Germany : Upper Germany and Lower Germany 15 . To contain the barbarians, the Romans try to federate them to the empire by establishing peace treaties ( fœdus ) where the barbarians are granted territories, develop trade with Rome , pay taxes and provide soldiers, advancing the Roman influence 16 . The most Romanized peoples adopt Christianity as the Burgundians , Ostrogoths , Vandals and especially the Visigoths 11 but in its Arian version 12 . The influx of “barbarian” peoples more or less Romanized shakes the unity that Christianity had in the empire, and in Gaul, the establishment of barbarian kingdoms, either pagan or Arian, declines the conciliar obedience faithful to the dogmas from Chalcedon, Constantinople, and Nicea.

Paganism, Arianism and the Conciliar Church

The Franks constituted a league of Germanic people who, although having established a fœdus with the empire, 17 remained pagan. They share with the other tribes of Germania the Ases worship of which the royal families are supposed to descend 18 . As a result, barbarian kings have a sacred origin making them both warlords but also holders of spiritual power. Also, when a “barbarian” leader turns to Christianity to try to get closer to the Romanized indigenous populations 12 , he opts instead for Arianism 19 , which allows the king to identify with Christ Superman 11 and to become the head of the Church, and thus to preserve his religious power 20 . The barbarian king thus concentrates the powers of warlord (or army king: heerkönig 21 ), head of state and head of the Church in his hands 11 , causing a Caesaro-papism 20 . On the contrary, the conciliar church preaches the division of powers between the king, laic , holder of temporal power , and the pope , superior pontiff , holder of spiritual power for the West.

The Germanic kingdoms at the end of the fifth century

At the end of the fifth century, Gaul was divided into several barbarian kingdoms, constantly at war, seeking to expand their influences and possessions. Three main sets stand out:

- the Franks, established in the north-east, having long served the Roman Empire as auxiliary troops on the Rhine frontier, still pagan at the advent of Clovis, themselves scattered in many different kingdoms;

- the Burgundians , established by Rome in Savoy (in Sapaudie ) and in the Lyonnais , Arian Christians and relatively tolerant;

- the Visigoths , a powerful people established south of the Loire , in Languedoc , especially in the valley of the Garonne , and in Spain, also Arians, but less tolerant towards the conciliar Christians whom they dominate;

- the Ostrogoths are only present in Provence (as far as Arles), but their king Theodoric the Great , from Italy, tries to maintain the equilibrium between the different kingdoms;

- Moreover, in the distance, the Eastern Roman Empire exerts a largely theoretical authority, but which retains an important symbolic value of which the Germanic sovereigns are eagerly seeking recognition. The Empire strives to contain the Germanic rulers.

Finally, a multitude of local or regional “powers” of military origin (“kingdoms” or regna ) thus occupy the void left by the deposition of the last Roman emperor of the West in 476 . Among these is the kingdom of a Roman general established in the region of Soissons , Syagrius . The “power” in question here has nothing to do with modern notions of legislative, executive or judicial power, but covers a dominant-dominated relationship closer to that of a tribal leader.

Biography of Clovis

Birth and Training

Childhood

Clovis was born in the year 466 22 , in the family of Merovingian kings. He is the son of Childeric I , king of the Salian Francs of Tournai , and Queen Basine of Thuringia .

Gregory of Tours makes Childeric I appear in his story in 457 23 , when Childeric, who dishonored the women of his subjects, provoked the anger of his people who drove him away. He then fled to Thuringia for eight years, probably from 451 24 . Living with King Basin , he seduces the wife of his host, Basine , whom he brings back with him when the Franks Saliens claim on the throne. King marries Basine. From this marriage Clovis is born.

Three other children are born from this union:

- Alboflede or Albofledis, baptized at the same time as his brother, who becomes a religious but dies soon after Note 4 ;

- Lantilde or Landechildis, mentioned briefly by Gregory of Tours when she too is baptized at the same time as her brother Note 5 ;

- Audoflede or Audofledis, whom Clovis married in 492 to Theodoric the Great , king of the Ostrogoths of Italy 25 .

Childeric, exercising administrative functions, must reside in one or more cities of Belgium second and occupy the palace assigned to the attention of the Roman governors . His son must have been born in Tournai and received, according to Germanic customs, a pagan baptism. His godfather named him Chlodweg and plunged him into the water eight days after his birth. His education had to be in the part of the residence reserved for women, the gynaeceum . Around six or seven years old, his father had to take charge of his education 26 by offering him an iron helmet, a shield and a scramasaxe used for the parade. Even if his majority is fixed at twelve 27 , it is not possible for him to fight before the age of fifteen 28 . He receives instruction based on the war: sports activities, horse riding and hunting. He speaks French , and having to succeed his father at the head of a Roman province , he learns Latin . Nevertheless, it is not possible to prove that he was able to read and write. He must also have been taught the history of his people.

The name of Clovis: etymology

Like all Franks from the beginning of the Christian era, Clovis spoke one or several Germanic languages of the so-called Low Franc linguistic subgroup.

The name of Clovis comes from Chlodowig , composed of the roots hlod (“fame”, “illustrious”, “glory”) and wig (“battle”, “fight”), that is “illustrious in the battle” or “fight of glory” 30 .

Frequently used by the Merovingians , the root hlod is also at the origin of names such as Clotaire ( Lothaire ) and Clodomir , Clodoald or Clotilde .

The name of the Frankish king derives then from “Hlodovic” then “Clodovic” who, Latinized in Chlodovechus , gives Chlodweg, Hlodovicus , Lodoys, Ludovic , “Clovis” 31 and “Clouis”, which was born in modern French the first name Louis , carried by eighteen kings of France. He also gives Ludwig in German.

The Latin “Claudius” leads both to the French “Louis” and to the German “Ludwig” (Clodweg, Cludwig) 32 .

The advent of Clovis

At the death of his father in 481 or 482 , Clovis inherited a kingdom that corresponds to the second Belgium (about the region of Tournai in Belgium today), a small province located between the North Sea , the Scheldt and the Cambresis , a territory ranging from Reims to Amiens and Boulogne , with the exception of the region of Soissons , which is controlled by Syagrius .

Clovis takes the lead of the Frankish-French kingdom. The title of “king” (in Latin rex ) is not new: it is particularly devolved to the warlords of the barbarian nations in the service of Rome. Thus, the Franks, former faithful servants of Rome, remain no less Germans , pagan barbarians , far removed by their way of life Gauls Romanized by nearly five centuries of domination and Roman influence.

Clovis is then only fifteen years old and nothing predisposes this little barbarian leader among many others to supplant his rivals, more powerful. Historians have long debated the nature of Clovis’ seizure of power. In the eighteenth century , they clash on the interpretation of a letter from Bishop Remi de Reims . Montesquieu , in the Spirit of Laws , leans towards a conquest of the kingdom by arms, while the abbot Dubos Note 6 advocates the devolution, by the Roman Empire ending, of Belgium second to the Merovingian family 33]. . Today, this last thesis prevails.

In the light of subsequent events, his undeniable military success obviously owes to his personal qualities as a very cunning leader (” astutissimus ” 34 ), but at least as much to his long- standing acquaintance with the Roman experience of the war – the discipline required of his soldiers during the episode of Soissons testifies, as the grave of his father Childeric – that his conversion to Christianity and, through it, his alliance with the Gallo-Roman elites .

Thus, the reign of Clovis is rather in the continuity of late antiquity in the High Middle Ages for many historians. It contributes, however, to forge the original character of this last period by giving birth to a first dynasty of Christian kings and, because of its acceptance by the Gallo-Roman elites, creating an original power in Gaul.

The extension of the kingdom of Clovis to the east and the center

All his life, Clovis strives to enlarge the territory of his kingdom, before, according to the Germanic tradition, that his children do not share it between them. Little by little, Clovis thus conquers all the northern half of present-day France: he combines himself first with the Rhenish Franks, then with the Franks of Cambrai whose King Ragnacaire is probably one of his parents 35 .

Territorial expansion policy

To ensure the expansion of his domain, Clovis does not hesitate to eliminate all obstacles: he thus assassinates all the neighboring Salian and Rhenish leaders, and also to ensure that only his sons will inherit his kingdom, some of his old companions and even some members of his family, including distant ones. In 490, he began a series of offensives against the Rhineland and Trans-Rhine Germania .

He thus launches into a great series of alliances and military conquests, at the head of only a few thousand men at the start. But more than the weapons, certainly effective, Franks, it seems that the know-how acquired in the service of the Roman Empire and against other barbarians that makes possible the military successes of the warriors of Clovis.

Through him, however, it is not a Germanic people who imposes itself on the Gallo-Romans: it is the fusion of German and Latin elements that continues. Thus, while Chlodowig (Clovis) has a barbaric name and Syagrius is nevertheless described as “Roman” by the sources, it does not clearly benefit from the support of his people. The “barbarian” Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great , in his prestigious court of Ravenna , also perpetuates all the characters of late Roman civilization, while remaining an Arian Ostrogoth, a heretical barbarian in the eyes of the Church.

In spite of hard fights, however, Clovis knows how to impose himself fairly quickly because he already seems rather Romanized and, finally, a less bad master than most pretenders: “at least he is a Christian,” the Gallo Roman. He also had a Gallo-Roman adviser, Aurelianus 36 . Conversely, the Visigoths, Christians but Arians, hold Aquitaine with an iron fist and make no effort to attempt a rapprochement with the Gallo-Roman Christians they dominate.

The conquest of the kingdom of Syagrius

From 486 , Clovis leads the offensive to the south. He took the towns of Senlis , Beauvais , Soissons and Paris and looted them. He delivers the battle of Soissons against Syagrius . The latter, son of the magister militum for Gallia Ægidius , is entitled “King of the Romans” and controls a Gallo-Roman enclave located between Meuse and Loire, the last fragment of the Western Roman Empire. The victory of Soissons allows the kingdom of Clovis to control all the north of Gaul. Syagrius took refuge with the Visigoths, who delivered him to Clovis the following year. The Gallo-Roman chief is discreetly slaughtered.

The legend of the vase of Soissons

It was after this battle that, according to Gregory of Tours, the episode of the vase of Soissons took place , where, against the military law of partition, the king asked to remove from the booty a precious liturgical vessel to make it, at the request of Remi , bishop of Reims, to the church of his city. After collecting the loot, Clovis asks his warriors to be able to add the vase to his share of the spoils. But a warrior opposes it by striking the vase with his ax. Clovis does not show any emotion and still succeeds in returning the ballot box to Remi’s envoy, but in resentment.

The epilogue occurs on . Clovis ordered his army to meet at the Champ-de-Mars , according to a Roman practice, an inspection of the troops and examine whether the arms are clean and in good condition. Inspecting his soldiers, he approaches the warrior who, the year before, had struck the vase intended for Remi and, under the pretext that his arms are poorly maintained, then throws the soldier’s ax to the ground. As he bends down to pick it up, Clovis kills his own ax on the unfortunate man’s head, killing him dead. On the orders of Clovis, the army must withdraw in silence, leaving the body exposed to the public 35 .

The testament of Saint Remi mentions a silver vase that Clovis would have given him, but that he would have melted to make a censer and a chalice.

The alliance with the Rhine Francs

Before 486 , Clovis chose to strengthen his positions by contracting a marriage 38 with a princess of the Frankish Frankish monarchy 39 , from which a son was born, Thierry 38 .

This union has often been interpreted as the episode of a tactical alliance with its eastern neighbors, allowing it to turn its ambitions south. This union with a wife called “second rank”, seen as a “pledge of peace” ( Friedelehe ), ensures peace between Rhenish Francs and Salians. It has often been misinterpreted as a concubinage by Roman Christian historians who did not know the mores of Germanic polygamous family structures without public marriage. Official (first rank) marriages allowed the wife to enjoy the “morning gift” ( Morgengabe Note 7 ), which consisted of movable property donated by the husband, as well as to command her legitimate descendants.

The kingdom of the Rhine Franks extends dangerously over the second Belgium but the alliance with Clovis assures them the possession of the cities of Metz , Toul , Trier and Verdun that the Alamans threaten 40 . Refusing to be attacked on two fronts, the strategy requires Clovis to attack the Rhineland Thuringians, who the expansion of their kingdom based on the Elbe and the Saale is overflowing on the right bank of the Lower Rhine, absorbing Regensburg by the same occasion and advancing the Alamans towards the Franks 41 .

The alliance with the Romans

In 508 , after his victory over the Visigoths, Clovis received from the Eastern Emperor Anastasius I “consular tablets” 42 , which is interpreted as an honorary consul title with consular ornaments 43 , 44 , and he is hailed as ” Augustus ” during a ceremony in Tours. This marks the continuation of good relations with the Roman Empire of which Constantinople is the only capital, Rome defeated in 476 having returned the imperial insignia and retaining only a spiritual authority strongly subject to imperial authority. The bishop-patriarch of Rome has not yet resumed (officially) the imperial title of Pope ( pontifex maximus ) or leader of the Roman religion in force since 712 BC. J.-C., titulature resumed by Theodore I only in 642.

The submission of Thuringia

In 491 , Clovis declares war on the Thuringians , whose hypothesis is that the kingdom is in fact similar to that of the King of the Salarian Franks Cararic , whose capital was the city of Tongeren 45 and whose outline is poorly defined. but probably extends to the region of Trier or the mouths of the Rhine . Cararic joined Clovis in the war against Syagrius, so he is his ally. But he would have waited for the battle to intervene with the victor, something that Clovis does not appreciate, which ends up submitting him 35 and shearing him with his son to get them into the orders, respectively as a priest. and deacon . After being aware of death threats against him, Clovis finally makes them murder and seizes the kingdom 47 .

A second hypothesis is that this war is simply the answer to the Thuringians’ threat to the Frankish kingdoms. Before 475 , the king of the Visigoths Euric allied with this people, just after defeating the Salian Franks, whose pirates attack the west coast of Gaul.

Basine, Clovis’ mother, being a Thuringian, an explanation for this war expedition gives credence to the idea that Clovis is trying to recover the territory from which his mother was born. 23 This expedition does not, however, undermine the sovereignty of Thuringia since it is necessary to await the reign of his sons, Thierry I and Clotaire I , so that it is fully subject, partly attached to the kingdom of the Franks 49]. and partly to the Saxon territories 50 .

Conversion to Catholic Christianity

The second marriage

The bishop of Rheims , the future saint Remi , then probably seeks the protection of a strong authority for his people, and writes to Clovis from the time of his accession. There are many contacts between the king and the bishop, the latter first encouraging Clovis to protect the Christians present on its territory. Thanks to his charisma and perhaps because of the authority he enjoys, Remi knows how to make Clovis respected and even serves as an advisor.

Following repeated embassies with King Gondebaud , Clovis chose to marry Clotilde , a Christian princess of high lineage, daughter of the king of the Burgundians Chilperic II 38 and Queen Caretene 51 (this people neighboring the Frank was established in the current Dauphine and Savoy ).

The marriage which takes place in Soissons Note 8 in 492 52 or in 493 53 concretizes the pact of non-aggression with the Burgundian kings . By choosing a descendant of King Athanaric of the Balthes dynasty, Clovis married a first-rate wife who assured him of a hypergamous marriage, allowing him to hoist the Franks to the rank of great power.

Therefore, according to Gregory of Tours , Clotilde does everything to convince her husband to convert to Christianity . But Clovis is reluctant: he doubts the existence of a single God; the infant death of his first baptized son, Ingomer , only exacerbates this mistrust. On the other hand, in accepting to convert, he fears losing the support of his people, still pagan: like most Germans, they consider that the king, warlord, is only worth the favor that the gods grant him in battle. If they convert, the Germans become rather Arian , the rejection of the dogma of the Trinity favoring somehow the maintenance of the elected king of God and head of the Church.

Nevertheless, Clovis more than anything needs the support of the Gallo-Roman clergy, because the latter represents the Gallic population. The bishops , who play the leading role in the cities since the civil authorities erased, remain the real masters of the cadres of the ancient power in Gaul. That is also areas where wealth was still concentrated. However, even the Church struggles to maintain its coherence: bishops exiled or not replaced in Visigoth territories, difficult pontifical successions in Rome , disagreement between pro-Visigoths Arians and pro-Franks (Remi de Reims, Genevieve of Paris …), etc.

The conversion and the battle of Tolbiac

It was in “the fifteenth year of his reign”, that is to say in 496 , that the Battle of Tolbiac ( Zülpich near Cologne ) took place against the Alamans , Clovis helping the Rhine Franks, including the King Sigebert had a knee injury 56 . According to Gregory of Tours, not knowing which pagan god to vow and his army being about to be defeated, Clovis then prays to Christ and promises to convert if “Jesus that his wife Clotilde proclaims son of God alive “gave him the victory Note 9 . This is the same promise made by the Roman emperor Constantine in 312 during the Battle of Milvian Bridge . Gregory of Tours takes up the Constantinian model (conversion after a battle, important role of a woman, Helen and Clotilde) to repeat what was most glorious and legitimize the Frankish kingship.

At the heart of the battle, while Clovis is surrounded and will be captured, the Alaman leader is killed by an arrow or an ax, which puts his army in rout. Victory is in Clovis and the god of Christians. One hypothesis is that the battle took place in 506 because of a letter from Theodoric sent in late 506 or early 507 to Clovis where mention is made of Clovis’ victory over the Alamans whom Theodoric took under his protection, the death of their king, and their escape into Rhaetia . It is also possible that there were two battles against the Alamans, one in 496 and the other in 506, where each time, their king perished in battle 59 . This victory allows the kingdom of Clovis to extend to the Upper Rhineland .

According to other sources 60 , Tolbiac was only one stage and the final illumination of Clovis would have taken place during the visit to the tomb of Martin de Tours .

According to Patrick Périn, medievalist, early medieval specialist and director of the National Archeology Museum, Clovis would not have made the vow to convert to Christianity during the famous Battle of Tolbiac but in an unknown battle. Indeed, the Battle of Tolbiac would be mentioned by mistake in the writings of Gregory of Tours . If the latter evokes Tolbiac well, it would be about the battle of Vouillé where was present Clodoric, son of Sigebert the lame of Cologne, so named because he had been wounded in a battle against the Alamans, Tolbiac. It would be historians of the nineteenth century who would have associated Tolbiac with the conversion of the King of the Franks [ref. insufficient] .

The catechumenate

Bishop Remi taught Clovis catechesis during the auditors’ phase ( audientes ) according to the precepts of the Councils of Nicaea (325), Constantinople ( 381 ) and Chalcedon ( ). He sees himself at length teaching morality and ritual, as well as the history of salvation 61 , then Trinitarian dogma and Credos such as “I believe in God Almighty Father and Jesus Christ his only begotten son, and not created “that the Council of Nicaea promulgated 14 . However, the doubt hangs over the Passion : Clovis does not believe that a true God can let himself be crucified Note 10 and thinks helpless 62 . Moreover, his sister Lantechilde pushes him to embrace Arianism rather than conciliar orthodoxy 13 .

Still is that during Christmas of a year Note 11 between 496 and 511 , perhaps in 499 63 or in 508 64 according to the authors, Clovis goes to the phase of the applicants ( competent ) 61 and then receives baptism with 3,000 warriors 65 , Note 12 – collective baptisms then being a common practice – from the hands of Saint Remi , the bishop of Reims, on December 25th . This figure is however questionable and the post-baptismal anointing is certainly excluded: it would have been difficult for the bishop to spread chrism, a mixture of olive oil and aromatic resin, on the front of 3,000 persons 66 . This baptism remained a significant event in the history of France: from Henry I all the kings of France , except Louis VI , Henry IV and Louis XVIII , are later crowned in the cathedral of Reims until King Charles X , in 1825 .

The baptism of Clovis undoubtedly increases its legitimacy among the Gallo-Roman population, but represents a dangerous bet: the Franks, like the Germans, consider that a chief is worth by the protection inspired by the gods; conversion goes against that; the Christianized Germans (Goths …) are often Arians , because the king remains there head of the Church. According to the historian Leon Fleuriot 67 , Clovis made a pact with the Britons and Armoricans of the west that he could not beat, while threatened the Visigoths. Baptism was a condition of this treaty because the Bretons were already Christianized. This treaty was concluded through Saint Melaine of Rennes and Saint Paterne de Vannes. The Bretons recognized the authority of Clovis but did not pay tribute.

Thus, the baptism of Clovis marks the beginning of the link between the clergy and the Frankish monarchy. For French monarchists, this continuity is French and lasts until the early nineteenth century . Henceforth, the sovereign must reign in the name of God. This baptism also allows Clovis to establish his authority over the populations, mainly Gallo-Roman and Christian, which he dominates: with this baptism, he can count on the support of the clergy , and vice versa. Finally, since this baptism, the French nationalist historiography of the nineteenth century attributed to the kings of France the title, erroneously historically speaking, ” eldest son of the Church ” 68 .

The baptism of Clovis according to Gregory of Tours

“The queen then secretly calls Remi, bishop of the city of Rheims, begging him to insinuate the word of salvation to the king. The bishop who had secretly summoned him began to insinuate that he must believe in the true God, creator of heaven and earth , and abandon idols which can not be useful to him or to others. But the latter replied: “I have listened very willingly to you, Most Holy Father, but there is one thing left; it is because the people who are under my orders do not want to abandon their gods; but I will maintain it according to your word. “

He went therefore to the midst of his people, and even before he had spoken, the power of God having preceded him, all the people cried at the same time: “The mortal gods, we reject them, pious king, and it is the immortal God Remi preaches that we are ready to follow . “ This news is brought to the prelate who, filled with great joy, had the pool ready. […] It was the king who first asked to be baptized by the pontiff. He steps forward, new Constantine, towards the pool to heal the disease of an old leprosy and to clear with fresh water of dirty stains made formerly.

When he entered for baptism, the saint of God spoke to him in an eloquent voice, saying, “Curl your head gently, O Sicambre; Note 13 love what you burned, burn what you loved . “ Remi was a bishop of remarkable science and first of all imbued with the study of rhetoric.There is nowadays a book of his life which tells that he was so distinguished by his holiness that he equaled Silvestre by his miracles, and that he raised a dead person. So the king, having confessed God Almighty in his Trinity, was baptized in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit and anointed with the holy chrism with the sign of the cross of Christ. More than three thousand men from his army were also baptized. […] »

– Gregory of Tours , History of the Franks , book II, chapter XXXI.

The extension of the kingdom to the south

Three powers exercise their domination in the south of the kingdom of Clovis, the Visigoths in the south-west, the Burgundians in the south-east and further, in Italy, the Ostrogoths. Clovis builds successive alliances to continue the expansion of his kingdom without having to face a hostile coalition against him.

Shifting alliances between Burgundians and Visigoths

In 495, Theodoric , king of Italy, wife Audofleda , sister of Clovis I st , which he tries to contain the growing ambition. The following year, he agrees with Clovis so that it does not continue beyond the Danube Alamans . Théodoric also protects the survivors by installing them in the first Rhetia . He has the advantage of repopulating a country and acquiring brave and faithful vassals.

In 499 , Clovis allies with the Burgundian king of Geneva , Godégisile , who wants to seize the territories of his brother Gondebaud 69 . In order to secure his territories in the West, in 500 , Clovis signed a pact of alliance with the Armoricans (Gallic tribes of the Breton peninsula and the shore of the Channel) 70 and Bretons 71 .

After the battle of Dijon and his victory over the Burgundians of Gondebald Clovis forced it to give up his kingdom and take refuge in Avignon 69 . However, the Visigoth king Alaric II goes to the rescue of Gondebaud and persuades Clovis to abandon Godégisèle. Clovis and Gondebaud reconcile and sign a covenant to fight the Visigoths .

To show the balance of its alliances, in 502 , his son Thierry first married a princess Rhine, which he Thibert I first king of Reims (548) and second wife Suavegotha , daughter of Sigismund , king of Burgondes, of which he has a daughter Theodechilde.

The Battle of Vouillé

With the support of the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius , who was very anxious about the expansionist aims of the Arian Christian Goths , Clovis then attacked the Visigoths who dominated most of the Iberian Peninsula and the south-west of Gaul. Septimanie or ” Marquisate of Gothie “), to the Loire in the north and to the Cevennes in the east.

In the spring of 507 , the Franks launch their offensive towards the south, crossing the Loire towards Tours , while the Burgundian allies attack to the east. The Franks face the army of King Alaric II in a plain near Poitiers . The so-called battle ” Vouillé ” (near Poitiers ), is terrible as historiography, and the Visigoths fell back after the death of their king, Alaric II was killed by Clovis himself in single combat 56 .

This victory allows the kingdom of Clovis to extend in Aquitaine and to annex all territories previously Visigoths between Loire, Ocean and Pyrenees . The Visigoths have no alternative but to retreat to Hispania , beyond the Pyrenees. However, the Ostrogoths of Theodoric try to intervene in favor of the Visigoths. They resumed well Provence after the lifting in the autumn 508 of the siege of Arles as well as some parts to the Burgondes, but the Empire of the East threatens their coasts, and Clovis keeps most of the former territories Visigoths. The Visigoths retain onlypart of Septimania – Languedoc – and Provence.

Clovis strengthens his power

Paris, the new capital of the united kingdom

He decided to make Paris , the city of St. Genevieve which the royal couple did replace the wooden building dedicated to him by a church 72 his residence 73 , after Tournai and Soissons 74 . This is the first accession to the status of capital of ancient Lutetia , which now bears the name of the former Gallic people Parisii .

His reasons are probably mainly strategic, the city has been a garrison town and an imperial residence by the end of the Empire, including the emperors Julian and Valentinian I st . It also benefits from natural defenses and good location 75 , Childeric I first tried to take it in besieging twice unsuccessfully 72 . Its location corresponds to the present island of the City connected to the banks of the Seine by a bridge to the north and a second bridge to the south, and protected by a rampart 76 . In addition, a vast and richtax (land, forest or mine belonging to the crown 77 ) surrounds it. It has only a relative importance: the Frankish kingdom has no administration, nor indeed any of the characteristics which found a modern state. However, the city of Lyon , former “capital of Gaul”, permanently loses its political supremacy in the West European isthmus.

During the reign of Clovis in any case, the city knows no major changes: the ancient real estate heritage is preserved, sometimes reallocated. Only new religious buildings donated by the royal family and the aristocracy are transforming the urban landscape, such as the Basilica of the Holy Apostles . But it is especially after the death of Clovis that the first of these buildings are born.

The two years before his death 78 , Clovis seized the Frankish kingdom of Sigebert the lame after having it murdered through his own son Clodéric , who perished in turn after a maneuver by Clovis, which extends his authority beyond the Rhine 79 . Clovis executes his kings Cararic and Ragnacaire , with his brother Riquier, and Rignomer, in the city of Le Mans, another of his brothers, to seize their kingdoms and prevent his unified kingdom from being shared between them. the custom of tanistria 80 .

Clovis is now the master of a single kingdom, corresponding to a western portion of the ancient Roman Empire, ranging from the Middle Rhine Valley (the mouth of the Rhine is still in the hands of the Frisian tribes) to the Pyrenees, held by the Basques . The kingdom of Clovis does not include the island of Britain (present Britain), nor the Mediterranean regions, nor the valleys of the Rhone and Saone.

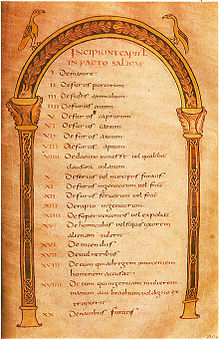

The salic law

In the Gallo-Roman subjects, Clovis enforces the Breviary of Alaric , Visigothic adaptation of the Theodosian code 81 . According to some historians, the first Salic Law was a penal code and civil , to own called Franks “Salian” ( IV th century). First memorized and transmitted orally, it was put in writing in the early years of the VI th century 82 at the request of Clovis 83 , then revised several times thereafter until Charlemagne. The pact of the Salic law is dated after 507: perhaps its promulgation coincides with the installation of the king in Paris?

The first version of the law (there were at least eight) bore the name of pactus legis salicæ (pact of the Salic law), and is composed of sixty-five articles. Seniority assumed this version drafted in Clovis, however, is disputed because if its origin dates back well in the middle of the VI th century, it is only due to a “first Frankish king” whose name is not specified 84. The prologue speaks of four rectors whose mission is to render equity and justice. A later prologue states that it was formatted by order of Clovis and his sons. The terms used in the written version and the principles applied are as much borrowed from Roman law as from the Germanic tradition. However, it is to substitute Roman law the barbaric customs to prevent private wars ( faides ) as a means of conflict resolution 85 . Unlike Roman law, the Salic law was much more lenient about the treatment meted out to criminals: various fines govern crimes, thus avoiding the death penalty 86 .

The Salic law applies to all Franks even Ripuarians whose Ripuarian law will be drafted much later, thereby assert their particularities 81 .

The Council of Orleans

In July 511 , Clovis meets a Council of Gauls in Orleans, which ends Sunday, July 10, 87 . The council brings together thirty-two bishops , and is presided over by the metropolitan bishop Cyprien of Bordeaux; half come from the “kingdom of the Franks”. The metropolitan bishops of Rouen and Tours are present but not that of Reims . The bishops of Vasconie are absent because of troubles in their region but also those of Belgium and Germany 88 because of the lack of penetration of theRoman Catholic Church in these regions. Clovis is designated ” Rex Gloriosissimus son of the Holy Catholic Church,” by all the bishops present 89 .

This council was crucial in establishing relations between the king and the Catholic Church. Clovis does not pose as a leader of the Church as an Arian king does, he cooperates with it and does not intervene in the decisions of the bishops (even if he has summoned them, asks them questions, and promulgates the canons of the council).

This council aims to restore order in the episcopate of the Frankish kingdom, to facilitate the conversion and assimilation of Francs converts and Arians, to limit incest (thus breaking the tradition of matriarchal German endogamous family clans), to share the tasks between administration and Church, to restore links with the papacy.

Of the thirty-one canons produced by the council, it appears that the king or his representative, that is to say, the count , are reserved the right to authorize or not the access of a layman to the clergy. Slaves must first refer to the master. This is to stem tax leakage that vocations, driven by immunity, cause among the richest 90 .

The king is given the right to appoint bishops, unlike the canon which wants them to be elected by an assembly of faithful, 91 thus confirming the rights of magister militum that the emperor granted to his ancestors as governors of the Province of Belgium second 92 . The Merovingian kings have this right until the promulgation of the Edict of Paris by Clotaire II , 18 October 614 93 where the episcopal elections again become the rule 94 . The chastity of the clergy and the subordination of the abbotsto the bishops are recalled. Heretical clerics who recognized the Catholic faith can regain function and religious institutions included the Arians were again established in the faith Catholic 84 .

The right of asylum is extended to all the buildings surrounding the churches, thus aligning with the Theodosian code , the Gombette law and the breviary of Alaric . The objective was to allow a fugitive to find refuge in the sacred buildings, with the assurance of being able to be properly housed without having to desecrate the buildings. The canon prohibits the prosecutor from entering the precincts of the building, without first swearing on the gospel , and inflict corporal punishment on the fugitive. Compensation was provided to compensate for the damage suffered, if it was a slave on the run, or the possibility for the master to recover it.

In case of perjury, there excommunication Note 14 . Royal lands granted to the Church are exempted from taxation in order to maintain the clergy, the poor and the prisoners. Many superstitions, such as ” spells of the saints “, the custom of opening at random the sacred books such as the Bible and interpreting as an oracle the text appearing in front of the reader’s Note 15 , are condemned 95 a second time, after the Council of Vannes of 465 96 .

The alliance of the Christian Church and power, which began with the baptism of the king and continues for nearly fourteen centuries, is a major political act that continues because the rural populations, hitherto pagan, more and more Christianized, trust him more.

The death and burial of Clovis

The Basilica of the Holy Apostles

Clovis dies in Paris on 2 , aged 45 98 . It is presumed that he died of an acute condition after three weeks 99 . According to tradition, he was buried in the basilica of the Holy Apostles (St. Peter and St. Paul) 100 , future church of St. Genevieve , he had built on the tomb of the same tutelary of the city, at the same time. location of the current rue Clovis (street which separates the Saint-Etienne-du-Mont church from the Henri-IV high school ).

Clovis was buried, as Gregory of Tours writes, in the sacrarium of the Basilica of the Holy Apostles under the present-day Clovis 101 , that is to say, in a mausoleum built expressly in the manner of the burial. had welcomed the Christian Roman emperor Constantine the Great to the Holy Apostles in Constantinople 102 , annex, probably grafted onto the bedside of the monument 103 . The royal sarcophagi were probably placed on the ground and not buried according to custom that was imposed upon the generation of the son of Clovis 103. Despite the wish of Clovis, the basilica did not serve as a mausoleum for the Merovingian dynasty. We do not know what happened to the tombs of the royal couple as well as those of their daughter Clotide, and their grandsons Thibaud and Gonthier, murdered at the death of Clodomir. As the example of the princely tombs of the Cologne Cathedral illustrates, it is possible that the sarcophagi were buried in the basement if an enlargement required its leveling 103 and if these works did not take place before the second half the IX th century, it is possible that they were looted or destroyed during the Norman invasions (845, 850 and 885).

The church was not destroyed because we were satisfied each time with some repairs. The shrines of the saints were evacuated in a safe place and then replaced after the attacks. If one is informed of the fate of the relics, one does not know however what became the tomb of Clovis during the Norman attacks.

The recumbent Clovis

In 1177, there was a tomb in the middle of the choir on which this inscription was written : ” chlodoveo magno, hujus ecclesiae fundatori sepulcrum vulgari olim lapidum structum and longo aevo deformatum, abbas and convent. meliori opere and form renovaverunt “. A recumbent statue of XIII th century was installed at the site of the tomb.

This tomb, composed of a base and a lying, was restored in 1628 by the care of the cardinal-abbot of La Rochefoucauld who had it placed in the rectangular axial chapel, at the bottom of the church, in a monumental baroque ensemble made of marble. It is this recumbent which was transferred in 1816 to the abbey church of Saint – Denis .

The excavations of 1807

In 1807 , at the time of the demolition of the church Sainte-Geneviève, excavations were undertaken by the prefect Frochot and conducted by the administration of Domains under the direction of architects Rondelet and Bourla, assisted by Alexandre Lenoir . Despite hasty and arbitrary identifications, the search of the crypt of the XI th century resulted in no significant discovery. No vestige dates back to the Merovingian period. On the other hand, the excavation of the nave allowed the discovery of 32 trapezoidal sarcophagi all oriented. This is because of the quality of the ornamentation, and because it was the purpose of the excavations and that the location corresponded to the recumbent XIII thcentury before transferring in 1628 , the report presented to the emperor concluded the probable discovery of sarcophagi of Clovis and his family 104 .

But Alexandre Lenoir recognized that no inscription attested it. The archaeologist Michel Fleury noted that the bill of these tombs is rather to place in the last quarter of the VI th century. It must not have been the burial place of Clovis and his family. It should rather be Merovingian aristocratic tombs placed ad sanctos , not far from the most likely location of the tomb of St. Genevieve between the VI th and XII th centuries. These sarcophagi did not seem, still according to Michel Fleury, to have been displaced during the reconstruction of the 11th century. century but should instead be at their original location.

Sixteen of the thirty-two sarcophagi were sent to the Museum of French Monuments in 1808 . They were lost in 1817 during the dissolution of the museum. From these excavations we have thus reached only a few rare elements and there is nothing to say with certainty that the tombs discovered were those of Clovis and his family.

The idea of relaunching excavations with modern means is defended for example by the historian Patrick Perrin. It is not excluded that new excavations at the site of the missing basilica, along the current rue Clovis, between the church of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont and the Lycée Henri IV could provide more precise information on the sacrarium arranged in 511 105 .

The succession

The descendants of Clovis

His first wife, a Frankish princess Rhine, Clovis had Thierry I st (c. 485-534), king of Reims from 511 to 534 and co-king of Orleans.

With Clotilde , he had:

- Ingomer or Ingomir, (died in 494 in his baptismal gown);

- Clodomir (v. 495 – 524 ), king of Orleans from 511 to 524, he married Gondioque of Burgundy;

- Childebert I st (c. 497 – 558 ), king of Paris from 511 to 558, wife Ultrogothe of Östergötland;

- Clotaire I er (c. 498 – 561 ), king of Soissons in 511, 555 in Reims and all the Franks in 558;

- Clotilde (died in 531 ), married in 517 Amalaric king of the Visigoths.

The division of the kingdom

On the death of Clovis, his son Thierry , Clodomir , Childebert and Clotaire share, according to Frankish tradition, the kingdom 106 he put a life together.

Most of Gaul having been submitted, except Provence , Septimania and the kingdom of the Burgundians , his kingdom can be divided into four parts, three of which are roughly equivalent. The fourth, between the Rhine and the Loire, is attributed to Thierry, the eldest son of Clovis, who had been a companion of his father’s fighting and was born of a pagan union before 493 . It is larger, since it covers about a third of Frankish Gaul.

Sharing takes place in the presence of the great of the kingdom, Thierry, who is already major, and Queen Clotilde, according to Gregory of Tours. It is established according to private law that Clovis had registered in the Salic law : in 511, it is therefore above all the sharing of a patrimony, that of the heirs of a king who owns his kingdom. In the light of this remark, we can understand that Frankish royalty ignores the notion of “public goods” (the res publica of the Romans ) and therefore of the state. The disappearance of the State , indeed, seems consumed through the division of the kingdom of Clovis.

This practice is very different from the sharing also practiced by the last Roman emperors: legally, the Empire remained one, the sharing was for practical reasons, the successors were chosen sometimes according to their merits. Even when it came to the emperor’s sons, the empire was not divided into as many parts as there were sons, and never was the empire separated from the notion of state by the Romans.

The heritage character of the division is particularly marked by the fragmentation of conquests located south of the Loire. Each one, to visit his domains of the south, is forced to cross the lands of one or more of his brothers.

However, noticeably, the four capitals of the new kingdoms are all located in the center of the complex, relatively close to each other and in the ancient kingdom of Syagrius: from then on, “there is a striking contrast between strong tendencies towards dispersal and the immanent force of a higher order unity: the idea of a united kingdom of the Franks remained anchored in the minds ” [ref. necessary] .The Frankish nation no longer returns to the state of tribes, and at least is no longer divided between salians and ripuaries .

General aspects of the reign

Clovis and the Church

Generosity being the first virtue of the Germanic king, it is translated by the gift to the churches of royal resources. Lands and treasures are systematically dilapidated to show his generosity to his faithful. Territorial expansion perpetuates donations 107 . The Council of Orleans is an opportunity to assure the dioceses 108 .

Several lives of saint attribute to the king the construction of various places of worship. Thus, in the life of St. Germier , bishop of Toulouse, is invited to the king’s table; Germier renowned for its virtues, attracts curiosity. The saint is the subject of admiration and granted land to Ox and treasures in gold and silver 109 .

Likewise at Auch, Metropolitan Bishop Perpet goes to meet Clovis when he is approaching the city to give him bread and wine. As a reward, the king offers the city to the saint, with its suburbs and churches, as well as his tunic and his coat of war at St. Mary’s Church. He sees also offer a treasure of gold and the royal church of Saint-Pierre-de-Vic 110 .

Clovis goes to Tournai to meet Saint Eleutherius , who guesses a king’s sin after his baptism. Clovis denies the facts and asks the bishop to pray for him. The next day, the bishop receives an illumination communicating to him the fault of Clovis, who is then forgiven. Saint Eleutherius then receives a donation for his church 111 .

Clovis is cured miraculously of a disease by St. Severin, abbot of St. Maurice in Valais . In gratitude, the king offers him money to distribute to the poor and the release of detainees 112 . From there would come the construction of the church Saint – Séverin of Paris 113 .

Hincmar wrote to 880 in his vita Remigii , Clovis granted the bishop Remi several donations territorial areas located in several provinces 114 including a field including Leuilly and Coucy, via a charter. Leuilly was awarded to Ricuin in 843 , a supporter of King Charles the Bald. In 845 , to force Ricuin Leuilly to restore the heritage of Reims, a false testament of the bishop Remi is presented to King Charles the Bald 115 .

In the XI th century, the hagiography of Leonardo Noblac claims that Leonardo Clovis sponsors at baptism, which the saint is granted the release of prisoners they visit and the gift of a bishopric. Leonard leaves the king to go to the forest of Pauvain in Limousin . Clovis then grant to Leonardo by an official act domain in the forest that the foundation of the church of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat 116 .

All his gifts bequeathed to the saints are just as hypothetical as unverifiable to the extent that at the time when life is written, no more witness can contradict the writings of the clergy who may have invented evidence by creating and attributing to King Clovis fake diplomas or false charters for religious communities 117 .

Clovis and power

If Clovis died in his bed in Paris on November 27, 511, he had, before and during his reign, killed by his hand, whether in combat, out of combat or by intrigues, several kings or sons of kings, among those Let’s quote 99 [ref. insufficient] :

- Chilperic II of Burgundy Prince Burgundian brother Gondégisile , Gondemar I st and Gondebaud father of Clotilde , wife of Clovis, slain by Gondebaud in 486 who drowned his wife by tying a stone around his neck, beheaded his two boys and sentenced her two girls in exile, as a result of intrigues with Clovis.

- Syagrius , dux Romanum of Soissons compete with Childeric I er , is murdered secretly in 486 on the orders of Clovis.

- Ragnacaire , king of Cambrai and his brother Riquier, in 489, killed with an ax by Clovis.

- Renomer , King of Le Mans , killed by order of Clovis in 489-490.

- Cararic king of the Morins and his son executed in 491 by order of Clovis.

- Gondégisile , king of Burgundy slaughtered, in 500, by Gondebaud , his brother, king of Burgondes as a result of intrigues with Clovis.

- Gondemar I er , brother Gondégisile , Chilperic II of Burgundy and Gondebaud , who was killed during the siege of Vienna in 501.

- Alaric II , king of the Visigoths killed in singular combat by Clovis, at the battle of Vouillé in 507.

- Sigebert the lame , king of the Franks of Cologne , killed voluntarily, in 507, by his son Clodéric during a hunt in the forest of Buconia , as a result of intrigues with Clovis.

- Clodéric the murderous son of Sigebert the lame , also killed in 507, during the unrest that followed the death of his father, by order of Clovis.

Clovis performances in history, literature and art

The legends around Clovis

The legend of the Troyes’ origin of the Franks brought Clovis down from the Trojan king Priam through Pharamond († 428), a more or less mythical leader.

Another legend, peddled by Archbishop Hincmar de Reims ( 845 – 882 ) in his Vita Remigii , which mixes the story of Gregory of Tours and an old hagiography of Saint Remi, now extinct, ensures that at his baptism, it is the Holy Spirit who took the form of a dove, brings the chrism , a miraculous oil in a bulb Note 16 .

While presiding at the coronation ceremony and coronation of Charles II the Bald as King of Lotharingia on September 9, 869 , Hincmar invents the coronation of Clovis, declaring that Charles descends from the “glorious king of the Franks Clovis, baptized the eve of Holy Easter Note 17 in the cathedral of Reims, and anointed and consecrated as king with the help of a chrism from heaven, which we still possess ” 119 .

The thaumaturgical power attributed to the kings of France to heal the sick, especially those suffering from scrofula , from Robert the Pious , sees its origin go back to Clovis, first Christian king 120 . In 1579 , a publication by Étienne Forcadel states that a squire named Clovis Lanicet fled the court of the king to hide his illness. Clovis dreams as he touches his squire, causing his healing. The next day, Clovis found his squire and running: the healing takes place 121 .

The French armorial shows Clovis emblazoned with lilies , virginal purity symbol represented by the Virgin Mary , in the XIV th century, but whose origin may date back to the XII th century 122 . An angel would have given to a hermit in the forest of Marly living around a tower called Montjoie, a shield with three fleurs-de-lis, in reference to the Holy Trinity. The hermit would have given it to Clotilde for it to give to the king to use it during the battle instead of his arms adorned with three croissants or three toads, the angel having assured the hermit that the shield ensures victory. When Clovis fights against his enemy and kills him near the Montjoie tower, he confesses the Trinity and founds the Abbey of Joyenval, which then welcomes the shield as a relic 123 .

Legend has it that Clovis and his descendants had broken teeth in a starry shape.

The painting The legend of Saint Rieul , painted in 1645 by Fredeau, exhibited at the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, reveals another legend. After Clovis built a church dedicated to Saint Rieul, Bishop Levangius would have given him a tooth taken in the mouth of Saint Rieul. The Frankish king could not have preserved it and would have been forced to put it back in the grave of the holy man.

Commemoration

In 1896, celebrations were organized by the Cardinal and Archbishop of Reims Benedict Langénieux for the 14 th centenary of the baptism of Clovis. In 1996-1997, the 15 th centenary of the baptism of Clovis (with the 16 th anniversary of the death of Martin of Tours ) was commemorated under the auspices of a committee for the commemoration of origins .

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Gregory of Tours , History of the Franks [ detail of the editions ] .

- Saint Genevieve of Paris. Life, worship, art (translated by Jacques Dubois and Laure Beaumont-Maillet), Beauchesne publisher, 1982 ( ISBN 978-2-7010-1053-3 ) .

- Marius of Avenches , Chronicle , “Sources of History” collection, Paléo editions, 2006 ( ISBN 978-2-84909-207-1 ) .

- The Book of the History of the Franks: Liber Historiae Francorum ( trad. Nathalie Desgrugillers-Billiard), Paleo editions ( ISBN 2-84909-240-1 ) .

- Documents on the reign of Clovis , translation by Nathalie Desgrugillers-Billard, Éditions Paleo, coll. the medieval encyclopedia ( ISBN 978-2-84909-604-8 ) .

- Charles De Clercq (abbot), The Frankish religious legislation of Clovis to Charlemagne: study on the acts of councils and capitulars, diocesan statutes and monastic rules (507-814) , Antwerp / Louvain / Paris, JE Buschmann / offices of the Collection, library of the University / Librairie du Recueil Sirey, , XVI -398 p. ( online presentation [ archive ] ) .

Contemporary Studies

XIX th century and first half of the XX th century

- Joseph Calmette , ” Observations on the chronology of the reign of Clovis ,” Proceedings of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres , Paris, Didier Henry, bookseller-publisher, n o 2, 90 th year, , p. 193-202 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Godefroid Kurth , Clovis , Tours, Alfred Mame and son, , XXIV -630 p. ( online presentation [ archive ] , read online [ archive ] )

Reissue: Godefroid Kurth , Clovis, the founder , Paris, Tallandier , coll. ” Biography “, , XXX -625 p. ( ISBN 2-84734-215-X )

- Jean Hoyoux , ” The Clovis Necklace “, Belgian Review of Philology and History , Brussels / Paris, Librairie Falk fils / Librairie E. Droz , t. XXI , , p. 169-174 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Leon Levillain , ” The Baptism of Clovis “, Library of the School of Charters , Paris, Librairie Alphonse Picard and son , t. LXVII , , p. 472-488 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Leon Levillain , ” The Conversion and the Baptism of Clovis “, Revue d’histoire de l’Eglise de France , vol. 21, n o 91, , p. 161-192 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Ferdinand Lot , ” The victory over the Alamans and the conversion of Clovis “, Belgian Review of Philology and History , Brussels / Paris, Librairie Falk fils / Librairie E. Droz , t. XVII , fascicles 1-2, , p. 63-69 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Louis Michel , ” About the history of Clovis’ necklace by Jean d’Outremeuse “, Belgian Review of Philology and History , Brussels / Paris, Librairie Falk fils / Librairie E. Droz , t. XXIII , , p. 264-268 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- André Van de Vyver , “Clovis and Mediterranean Politics” , in History Studies dedicated to the memory of Henri Pirenne by his former students , Brussels, New Publishing Company, , X- 504 p. ( online presentation [archive] ) , p. 367-388 .

- André Van de Vyver , ” The victory over the Alamans and the conversion of Clovis “, Belgian Review of Philology and History , Brussels / Paris, Librairie Falk fils / Librairie E. Droz , t. XV , fascicles 3-4, , p. 859-914 ( online presentation [ archive ] , read online [ archive ] ) .

- André Van de Vyver , ” The only victory against the Alamans and the conversion of Clovis in 506 “, Belgian Review of Philology and History , Brussels / Paris, Librairie Falk fils / Librairie E. Droz , t. XVII , fascicles 3-4, , p. 793-813 ( online presentation [ archive ] , read online [ archive ] ) .

- André Van de Vyver , ” The chronology of the reign of Clovis from legend and from history, ” The Middle Ages. Journal of History and Philology , Brussels, The Renaissance of the Book, vol. LIII , fascicles 3-4, , p. 177-196 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

Recent studies

German

- ( Of ) Eugen Ewig , Die Merowinger und das Frankenreich , W. Kohlhammer, al. “Urban-Taschenbücher” ( n o 392) , 6 th ed. ( 1 st ed. 1988), 280 p. ( ISBN 978-3170221604 , online presentation [ archive ] ) , [ online presentation [ archive ] ] .

English

- ( In ) Yitzhak Hen , ” Clovis, Gregory of Tours, and Pro-Merovingian Propaganda “ , Belgian Journal of Philology and History , Vol. 71, Issue 2 “Medieval, modern and contemporary history – Middeleeuwse, modern hedendaagse geschiedenis “ , , p. 271-276 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- ( In ) Danuta Shanzer , ” Dating the baptism of Clovis: the bishop of Vienna vs the bishop of Tours “ , Early Medieval Europe , vol. 7, n o 1, , p. 29-57 ( DOI 10.1111 / 1468-0254.00017 , read online [ archive ] ) .

- ( In ) Ian N. Wood , ” Gregory of Tours and Clovis “ , Belgian Journal of Philology and History , Vol. LXIII , issue 2 “Medieval, modern and contemporary history – Middeleeuwse, modern in hedendaagse geschiedenis “ , , p. 249-272 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

French

- Pascale Bourgain and Martin Heinzelmann , ” Curve, proud Sicambre, adore what you burned”: about Gregory of Tours, Hist. , II , 31 “, Library of the School of Charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz , t. 154, 2 e delivery , p. 591-606 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Geneviève Bührer-Thierry and Charles Mériaux , France before France: 481-888 , Paris, Belin, coll. “History of France” ( n o 1) , 687 p. ( ISBN 978-2-7011-5302-5 , online presentation [ archive ] ) , [ online presentation [ archive ] ] .

- Gaston Duchet-Suchaux and Patrick Périn, Clovis and the Merovingians , Paris, Tallandier, coll. “France over its Kings”, 2002, ( ISBN 978-2-235-02321-4 ) .

- Léon Fleuriot , The Origins of Brittany: Emigration , Paris, Payot, coll. “Historical Library” ( n o 34) ( 1 st ed. 1980), 353 p. ( ISBN 2-228-12711-6 , online presentation [ archive ] ) , [ online presentation [archive] ] , [ online presentation [archive] ] .

- Patrick J. Geary , The Merovingian World: Birth of France [“Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World”], Paris, Flammarion, coll. “Flammarion Stories”, , 293 p. ( ISBN 2-08-211193-8 , online presentation [ archive ] )

Reissue: Patrick J. Geary , The Merovingian World: Birth of France [“Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World”], Paris, Flammarion, coll. “Fields. History, , 292 p. Pocket ( ISBN 978-2-08-124547-1 ) .

- Marie-Céline Isaïa , Remi of Reims: memory of a saint, history of a Church , Paris, Editions du Cerf, coll. “Religious History of France” ( n o 35) , 919 p. ( ISBN 978-2-204-08745-2 , online presentation [ archive ] ) .

- Edward James , ” Childeric Syagrius and the disappearance of the kingdom of Soissons ,” Archaeological Review of Picardy , n o 3-4 “Acts of the VIII th International Days of Merovingian archeology of Soissons (19-22 June 1986)” , p. 9-12 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Stéphane Lebecq , New history of medieval France , vol. 1: The Frankish origins, V th – IX th century , Paris, Seuil, coll. “Points. History “( n o 201) , 317 p. ( ISBN 2-02-011552-2 ) .

- Renée Mussot-Goulard , Clovis , Paris, University Presses of France , coll. “What do I know? “ , 126 p. ( ISBN 978-2-130-48373-1 , OCLC 2130483739 ) .

- Patrick Périn , Clovis and the birth of France , Éditions Denoël , coll. “The History of France”, ( ISBN 978-2-207-23635-2 ) .

- Patrick Périn (with the collaboration of Monique and Gaston Duchet-Suchaux), Clovis. Archeology and history , Paris, Errance, 1996, 160 p.

- Patrick Périn , “The Grave of Clovis” , in Media in Francia: a collection of mixtures given to Karl Ferdinand Werner on the occasion of his 65th birthday by his French friends and colleagues , Maulévrier / Paris, Hérault / German Historical Institute, , XV- 551 p. ( ISBN 2-903851-57-3 , read online [ archive ] ) , p. 363-378 .

- Michel Rouche , Clovis , Paris, Editions Fayard, ( ISBN 2-2135-9632-8 ) , [ online presentation [ archive ] ] .

- Michel Rouche ( eds. ), Clovis, history and memory: proceedings of the International Congress of Reims, 19-25 September 1996 , vol. 1: The baptism of Clovis, the event , Paris, Presses of the University of Paris-Sorbonne, , XIX -929 p. ( ISBN 2-84050-079-5 ) .

- Michel Rouche ( eds. ), Clovis, history and memory: proceedings of the International Congress of Reims, 19-25 September 1996 , vol. 2: The baptism of Clovis, its echo throughout history , Paris, Presses of the University of Paris-Sorbonne, , XII- 915 p. ( ISBN 2-84050-079-5 ) .

- Georges Tessier , The baptism of Clovis: December 25, 496 (?) , Paris, Gallimard, coll. ” Thirty days that have made France ” ( n o 1) , 427 p. ( online presentation [ archive ] ) , [ online presentation [ archive ] ] .

Reissue: Georges Tessier , The baptism of Clovis: December 25, 496 (?) , Paris, Gallimard, coll. ” Thirty days that made France “, , 2nd ed. ( 1 st ed. 1964), 420 p. ( ISBN 2-07-026218-9 ) .

- Laurent Theis , Clovis, from history to myth , Brussels, Éditions Complexe, coll. “Time and men”, ( ISBN 978-2-87027-619-8 ) .

- Karl Ferdinand Werner (under the direction of Jean Favier ), Histoire de France , t. 1: The origins: before the year 1000 , Paris, Librairie générale française, coll. “References” ( n o 2936) ( 1 st ed. 1984 Fayard), 635 p. ( ISBN 2-253-06203-0 ) .

- Karl Ferdinand Werner , ” From Childéric Clovis: antecedents and consequences of the Battle of Soissons in 486 ,” Archaeological Review of Picardy , n o 3-4 “Acts of the VIII th International Days of Merovingian archeology of Soissons (19-22 June 1986) “, , p. 3-7 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

Historiography

- Christian Amalvi , ” The Baptism of Clovis: The Woes and Misfortunes of a Founding Myth of Contemporary France, 1814-1914 “, Library of the School of Charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 147, , p. 583-610 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Colette Beaune , Birth of the nation France , Paris, Gallimard, coll. “Library of Stories”, , 431 p. ( ISBN 2-07-070389-4 , online presentation [ archive ] ) , [ online presentation [archive] ] , [ online presentation [archive] ] .

Reissue: Colette Beaune , Birth of the nation France , Paris, Gallimard, coll. “Folio. History “( n o 56) , 574 p. Pocket ( ISBN 2-07-032808-2 ) .

- Colette Beaune , ” Clovis in the Dominican mirrors the middle of the XIII th to the end of the XIV th century ,” Library of the School of charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 113-129 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Philippe Bernard , ” ” Vestra fides nostra victoria is “Avitus of Vienne, the baptism of Clovis and the theology of the late-ancient victory ,” Library of the School of charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 47-51 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Pascale Bourgain , ” Clovis and Clotilde among medieval historians, Merovingian times in the first century Capetian ” Library of the School of Charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 53-85 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Carlrichard Brühl , ” Clovis among Forgers “, Library of the School of Charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 219-240 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Claude Carozzi , ” The Clovis of Gregory of Tours “, The Middle Ages , t. XCVIII ( 5 e series, Volume 6), n o 2 , p. 169-186 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Jean-Christophe Cassard , ” Clovis … do not know! A brand absent in medieval historiography Breton ” Medieval , Presses Universitaires de Vincennes , n o 37″ The year 2000 “ , p. 141-150 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Franck Collard , ” Clovis in France a few stories from the late XV th century ,” Library of the School of charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 131-152 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Chantal Grell , ” Clovis of the Great Century Enlightenment “, Library of the School of Charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 173-218 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Martin Heinzelmann , ” Clovis in the hagiographic discourse VI th to IX th century ,” Library of the School of charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 87-112 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Michel Sot , ” Clovis Baptism and the entry of Romanism in Franks ‘, Bulletin of the Association Guillaume Bude , Association Guillaume Budé , n o 1, , p. 64-75 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Michel Sot , ” What is left of the commemoration of the XV th centenary of the baptism of Clovis (1996)? ” Review of History of the Church of France , Paris, Society of Religious History of France, t. 86, n o 216, , p. 185-197 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Karl Ferdinand Werner , ” The Frankish conquest of Gaul: historiographical routes of error, ” Library of the School of Charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 7-45 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

- Myriam Yardeni , ” Clovis to Christianity XVI th and XVII th centuries ,” Library of the School of charters , Paris / Geneva, Librairie Droz, t. 154 “Clovis among historians”, 1996, 1 st delivery, p. 153-172 ( read online [ archive ] ) .

Literature

- François Cavanna , The Ax and the Cross , Editions Albin Michel , 1999 ( ISBN 978-2-226-11053-4 ) .

- François Cavanna, The God of Clotilde , Editions Albin Michel, 2000 ( ISBN 978-2-226-12016-8 ) .

- Max Gallo , The Baptism of the King , Editions Fayard, 2002 ( ISBN 978-2-213-61350-5 ) .

- Patrick Mc Spare , Merovingians: The kingdoms are born from the shadows , Paris, editions Pygmalion , 2017 ( ISBN 9782756419039 )

Notes and references

Notes

- This name is composed of the roots hlod ( “illustrious”) and wigs ( “struggle”). The initial [k] (c-) is linked to a scholarly Latinization intended to make the sound [x] unknown in Latin. The popular form is Louis , hence the use of the name Louis in many kings of the Franks and France later. Frequently used by the Merovingians , the root hlod is also the origin of names such as Cloderic , Clotaire , Clodomir or Clotilde .

- Thus the de Gaulle general , quoted by David Schoenbrun, in his biography The three lives of Charles de Gaulle (translated by Guy Le Clec’h), published by Julliard in 1965, said: “For me, the history of France begins with Clovis, chosen as king of France by the tribe of the Franks , who gave their name to France . Before Clovis, we have prehistory Gallo-Roman and Gallic. The decisive thing for me is that Clovis was the first king to be baptized a Christian. My country is a Christian country and I begin to count the history of France from the accession of a Christian king who bears the name of the Franks. “

- About twenty pages of current edition.

- Gregory of Tours, History , Book II, 31: ” It is also named his Alboflède sister, who, shortly after, went to join the Lord. As the king was afflicted with this loss, Saint Remi sent him, to console him, a letter which began thus: I am afflicted as much as I can with the cause of your sadness, the death of your sister Alboflede, of happy memory ; but we can console ourselves because it has come out of this world more desirous than weeping . “

- Gregory of Tours, ibid. : ” The other sister of Clovis, named Lantéchilde, which had fallen into the Arian heresy, converts; and having confessed that the Son and the Holy Spirit were equal to the Father, it was renamed “ .

- In his Critical History of the establishment of the French monarchy in Gaul , published in 1734 , he attempted to demonstrate that the Franks penetrate Gaul not as conquerors, but at the prompt of the Gauls.

- The Morgengabe existed among the Franks, Burgundians, Alemanni, Bavarians, the Anglo-Saxons, Lombards, Frisians and Thuringians. Rouche (1996), p. 237.

- Antoine Le Roux Lincy , Famous Women of ancient France: historical memories on public and private lives of French women, from the fifth century until the eighteenth , Leroy, ( read online [archive] ) , p. 78; According to other historians, the marriage took place in Chalon-sur-Saone: Bernard Durand, Leonard Bertaud and Pierre Cusset, The illustrious Orbandale or the ancient and modern history of the city and city of Chalon sur Saone, 1662 .

- He would have said, “God of Clotilde, if you give me the victory, I will be Christian” according to the testimony of Gregory of Tours.

- Chronic Fredegar made him say, “If I had been there with my Franks, I would have avenged this insult.” Rouche (1996), p. 263 ; Theis 1996 , p. 88

- The controversy took over at the official celebration of the 1500 th anniversary of the baptism of Clovis in 1996, especially on the occasion of the visit of Pope John Paul II in Reims. See Laurent Theis , “France, what did you do with your baptism? ” History , n o 331, May 2008, p. 82-85.

- The chronicle Fredegaire , resumes 93 chapters in his book III the books I to VI of stories Gregory of Tours, double the number of baptized warriors, from the 3 000-6 000 Fredegaire (trans. By O. Devilliers and J. Meyers), Chronicle of the Merovingian Times , Brepols edition, 2001, p. 7 ; Theis, Clovis, from History to Myth , 1996, p. 88.

- ” Mitis depone colla, Sicamber “. Theis 1996 , p. 44 proposes the following translation: “humbly deposit your necklaces, Sicambre”, that is to say, amulets referring to the gods gods related to the demons.

- Kurth (1896), p. 455; Gregory of Tours gives us the perfect example of circumvention of this canon through the account he gives us about the actions of Duke Rauching. op. cit. , book V, 3.

- An example is delivered by Gregory of Tours, when it hosts the prince Merovee in the Basilica of Saint Martin of Tours. op. cit. , book V, 14.

- “While they had arrived at the baptistery, the cleric who carried the chrism was stopped by the crowd, so that he could not reach the basin. After the blessing of the basin, the chrism failed by the design of God. And since, because of the press, no one could leave the church or enter it, the holy pontiff, with his eyes and hands directed towards the sky, began to pray crying. And suddenly a dove, whiter than snow, brought into its beak a light bulb full of holy chrism, whose wonderful odor, superior to all that had been breathed before in the baptistry, filled all the assistants with a infinite pleasure. The holy pontiff having received this light bulb, the shape of the dove disappeared. Hincmar of Reims, Vita Remigii .

- The chronicle of Fredegarius, book III, the baptism is the holy Saturday. It is this story that influences Hincmar’s words. ( Theis 1996 , 90)

References

- Theis 1996 , p. 101