The Château de Saumur holds a significant collection of ceramic art.

I will revisit the rooms later to take better images but the slides give an idea of the size of this permanent collection.

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

The Château de Saumur holds a significant collection of ceramic art.

I will revisit the rooms later to take better images but the slides give an idea of the size of this permanent collection.

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

Fuseau Vase Department of Decorative Arts: 19th century

On the baptism of his son, King of Rome, on 10 June 1811, Napoleon offered the infant’s godmother – his own mother, Madame Mère – this spectacular porcelain fuseau vase. The tortoiseshell ground provides a sumptuous setting for a portrait of Napoleon crossing the Alps, after David’s famous painting. The vase is typical of the designs of Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), director of the Sèvres Manufactory, who saw in porcelain a way of giving great history painting imperishable form.

Pair of Wall Sconces (Louvre Museum)

This pair of porcelain wall sconces is very unusual in its use of three different enamel grounds – blue, pink, and green. Each sconce consists of three curved branches decorated with leaves, typical of the Rocaille style. The sconces were the work of Jean-Claude Duplessis (died 1774) and come from the bedchamber of Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764) in the Hôtel d’Evreux, where she kept them along with her mantelpiece ornaments, also in the Louvre.

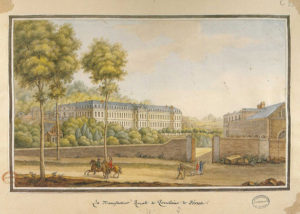

L’exploitation des carrières(1823) par Develly Jean-Charles (1783-1849)

Vincennes ware (Encyclopedia Britannica), pottery made at Vincennes, near Paris, from c. 1738, when the factory was probably founded by Robert and Gilles Dubois, until 1756 (three years after it had become the royal manufactory), when the concern moved to Sèvres, near Versailles. After 1756 pottery continued to be made at Vincennes, under Pierre-Antoine Hannong; both tin-glazed earthenware (officially) and soft-paste porcelain (clandestinely, in defiance of a Sèvres monopoly) were made until royal intervention forced Hannong’s dismissal in 1770. The factory continued until c. 1788. Histories of the royal porcelain manufactory of France usually discuss products before 1756 under the name Vincennes and those after 1756 under the name Sèvres, though when it comes to questions of patronage and style, pottery authorities refer freely to the Vincennes–Sèvres administration.

Some of the innovations for which Sèvres became famous actually began during the Vincennes period. Soft paste (a porcellaneous material but not true porcelain) was made from 1745 by François Gravant and a company formed with a monopoly of the production of “porcelain in the style of the Saxon.” Typical of Vincennes were biscuit figures (white mat, unglazed figures in soft paste) introduced c. 1751–53 by J.-J. Bachelier, and flowers (c. 1748), also modelled in soft paste, on wire stems or applied to vases.

Chantilly porcelain (Encyclopedia Britannica), celebrated soft-paste porcelain produced from 1725 to c. 1789 by a factory established in the Prince de Condé’s château at Chantilly, Fr. Two periods can be distinguished, according to the composition of the porcelain; in the first, up to about 1740, a unique, opaque milk-white tin glaze was applied on a rather yellowish body; in the second (1741–89), a traditional, transparent lead glaze was used.

Chantilly porcelain plate decorated with dragons, c. 1725; in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The preoccupation of Chantilly, until the Prince died in 1740, was with Japanese Kakiemon designs. Some of his designs were directly inspired by his large collection of the ware, others derived from Meissen versions of these Oriental motifs, such as the “Red Dragon” service, which, in iron-red and gilding, became the Chantilly Prince Henri pattern. Other Japanese patterns simplified and adopted included the quail, partridge, flying squirrel, and pomegranate.

Porcelain produced in the second period was influenced first by Meissen and then by Sèvres, both in modelling and in the use of coloured grounds. Some rare figures reflecting Chinese influence were modelled, as well as bird figures and small statuette flower holders. The main production, however, consisted of domestic ware—plates, jugs, basins, and jardinieres—enhanced by an effective economy of decoration painted in underglaze blue only or at best with a limited palette, which was the result of Royal edicts in favour of the Sèvres. The motif was often small flower bouquets known as Chantilly sprigs or more formal scrolls and plait work.

Porcelain was a relatively unknown commodity in seventeenth-century France. Examples of both Chinese and Japanese porcelain could be found in royal and aristocratic collections, but because of their cost, these objects were available only to the highest levels of society. Before the last decade of the seventeenth century, there was no domestic production of porcelain in France, and faience (tin-glazed earthenware) was the most common type of ceramic.

It is not surprising that the first porcelains produced in France were made at faience factories. Experiments in a Rouen faience factory owned by the Poterat family resulted in some of the earliest examples of soft-paste porcelain made in France. Soft-paste porcelain was a type of artificial porcelain that lacked the ingredients found in true or hard-paste porcelain. One of these ingredients, known as kaolin, was not discovered in France until the second half of the eighteenth century, and all French porcelain produced before 1770 was soft rather than hard paste.