L’exploitation des carrières(1823) par Develly Jean-Charles (1783-1849)

L’exploitation des carrières(1823) par Develly Jean-Charles (1783-1849)

Madame de Pompadour Royal Mistress and Patron of the Arts (1721-1764)

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour, commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, was a member of the French court and was the official chief mistress of Louis XV from 1745 to 1751, and remained influential as court favourite until her death.

Vincennes ware (Encyclopedia Britannica), pottery made at Vincennes, near Paris, from c. 1738, when the factory was probably founded by Robert and Gilles Dubois, until 1756 (three years after it had become the royal manufactory), when the concern moved to Sèvres, near Versailles. After 1756 pottery continued to be made at Vincennes, under Pierre-Antoine Hannong; both tin-glazed earthenware (officially) and soft-paste porcelain (clandestinely, in defiance of a Sèvres monopoly) were made until royal intervention forced Hannong’s dismissal in 1770. The factory continued until c. 1788. Histories of the royal porcelain manufactory of France usually discuss products before 1756 under the name Vincennes and those after 1756 under the name Sèvres, though when it comes to questions of patronage and style, pottery authorities refer freely to the Vincennes–Sèvres administration.

Some of the innovations for which Sèvres became famous actually began during the Vincennes period. Soft paste (a porcellaneous material but not true porcelain) was made from 1745 by François Gravant and a company formed with a monopoly of the production of “porcelain in the style of the Saxon.” Typical of Vincennes were biscuit figures (white mat, unglazed figures in soft paste) introduced c. 1751–53 by J.-J. Bachelier, and flowers (c. 1748), also modelled in soft paste, on wire stems or applied to vases.

Chantilly porcelain (Encyclopedia Britannica), celebrated soft-paste porcelain produced from 1725 to c. 1789 by a factory established in the Prince de Condé’s château at Chantilly, Fr. Two periods can be distinguished, according to the composition of the porcelain; in the first, up to about 1740, a unique, opaque milk-white tin glaze was applied on a rather yellowish body; in the second (1741–89), a traditional, transparent lead glaze was used.

Chantilly porcelain plate decorated with dragons, c. 1725; in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The preoccupation of Chantilly, until the Prince died in 1740, was with Japanese Kakiemon designs. Some of his designs were directly inspired by his large collection of the ware, others derived from Meissen versions of these Oriental motifs, such as the “Red Dragon” service, which, in iron-red and gilding, became the Chantilly Prince Henri pattern. Other Japanese patterns simplified and adopted included the quail, partridge, flying squirrel, and pomegranate.

Porcelain produced in the second period was influenced first by Meissen and then by Sèvres, both in modelling and in the use of coloured grounds. Some rare figures reflecting Chinese influence were modelled, as well as bird figures and small statuette flower holders. The main production, however, consisted of domestic ware—plates, jugs, basins, and jardinieres—enhanced by an effective economy of decoration painted in underglaze blue only or at best with a limited palette, which was the result of Royal edicts in favour of the Sèvres. The motif was often small flower bouquets known as Chantilly sprigs or more formal scrolls and plait work.

Colbert Visiting the Gobelins, Sébastien Leclerc I (French, Metz 1637–1714 Paris) 1665

This etching illustrates a visit to the Gobelins workshops by Colbert de Villacerf, Surintendant des Bâtiments du Roi from 1691 to 1699. The workers are in the process of hanging one of a set of tapestries depicting the Story of Alexander, woven for Louis XIV after designs by Charles Le Brun.

Photographie : Jean-Philippe Humbert

In 1662 the works in the Faubourg Saint Marcel, with the adjoining grounds, were purchased by Jean-Baptiste Colbert on behalf of Louis XIV and made into a general upholstery factory, in which designs both in tapestry and in all kinds of furniture were executed under the superintendence of the royal painter, Charles Le Brun, who served as director and chief designer from 1663-1690. On account of Louis XIV’s financial problems, the establishment was closed in 1694, but reopened in 1697 for the manufacture of tapestry, chiefly for royal use. It rivalled the Beauvais tapestry works until the French Revolution, when work at the factory was suspended.

The factory was revived during the Bourbon Restoration and, in 1826, the manufacture of carpets was added to that of tapestry. In 1871 the building was partly burned down during the Paris Commune.

The factory is still in operation today as a state-run institution. The manufactory consists of a set of four irregular buildings dating to the seventeenth century, plus the building on the avenue des Gobelins built by Jean-Camille Formigé in 1912 after the 1871 fire. They contain Le Brun’s residence and workshops that served as foundries for most of the bronze statues in the park of Versailles, as well as looms on which tapestries are woven following seventeenth century techniques. The Gobelins still produces some limited amount of tapestries for the decoration of French governmental institutions, with contemporary subjects.

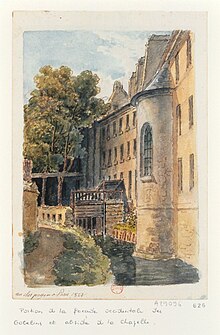

Rear view of the Gobelin Manufactory, adjoining the Bièvre river, in 1830.

Although Gobelins is synonymous with tapestry, the two brothers never wove a thread. Their claim to fame in the tapestry world was making a special Venetian scarlet dye.

Tapestries sought to technically compete with paintings. Hundreds of new dyes were developed to create a range of subtle tonal qualities. Unfortunately, the ravages of time and light have destroyed much of these subtle effects.

Click Refresh to view slides

Further reading

Further viewing

The Art of Making a Tapestry : The Tapestry Manufactory at the Gobelins, Paris