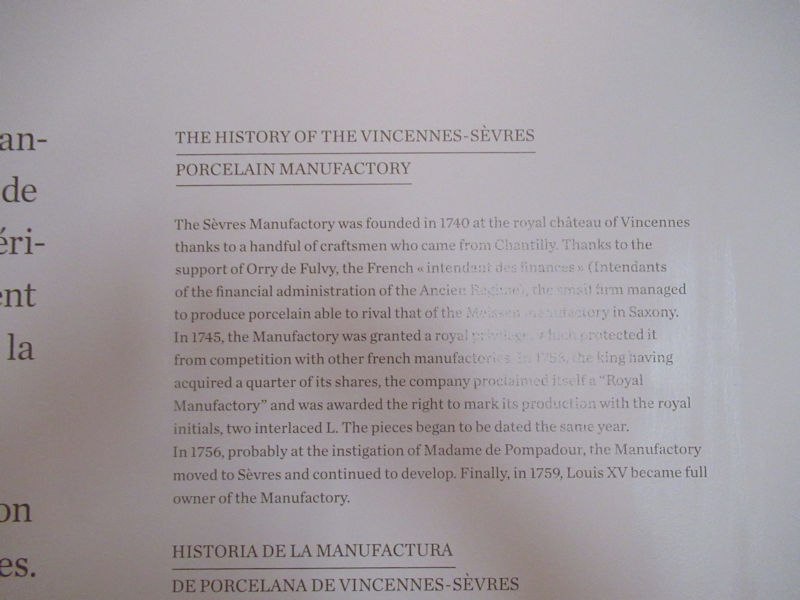

Sèvres porcelain, (Encyclopedia Britannica) French hard-paste, or true, porcelain as well as soft-paste porcelain (a porcellaneous material rather than true porcelain) made at the royal factory (now the national porcelain factory) of Sèvres, near Versailles, from 1756 until the present; the industry was located earlier at Vincennes. On the decline of Meissen after 1756 from its supreme position as the arbiter of fashion, Sèvres became the leading porcelain factory in Europe. Perhaps the major factor contributing to its success was the patronage of Louis XV’s mistress Madame de Pompadour. It was through her influence that the move was made from Vincennes to Sèvres, where she had a château, and through her that some of the foremost artists of the time, such as the painter François Boucher and the sculptor Étienne-Maurice Falconet (who directed Sèvres modeling between 1757 and 1766), became involved in the enterprise. It was after her that rose Pompadour was named in 1757; this was one of many new background colours developed at Sèvres, one of which, bleu de roi (c. 1757), has passed into the dictionary as a universal term.

One of the central preoccupations at Sèvres, in which such notable chemists as Jean Hellot were engaged, was the secret of hard-paste porcelain. Soft paste had been made at Vincennes from 1745, but the Sèvres factory did not obtain the secret of hard paste until 1761, when it was bought from Pierre-Antoine Hannong. The necessary raw materials, however, were still lacking in France; and it was not until these were found (1769) at Saint-Yrieix, in the Périgord district, that hard-paste porcelain could be produced. Thereafter a distinction was made in nomenclature between porcelaine de France or vieuse Sèvres (soft paste, or pâte tendre) and porcelaine royale (hard paste, or pâte dure).

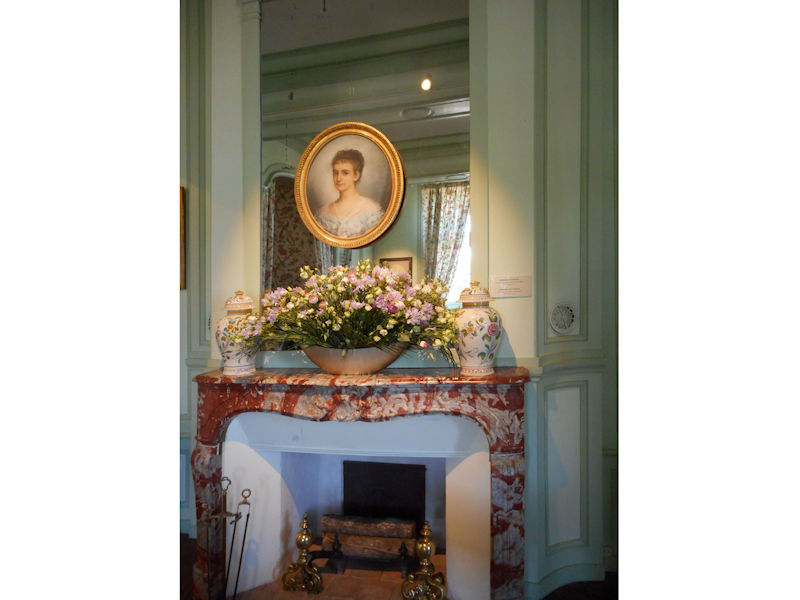

The industry suffered greatly during the French Revolution but revived in the early 19th century under the directorship of Alexandre Brongniart. After the Neoclassical and Egyptian styles of Napoleon’s empire, no one distinctive style was initiated. On the baptism of his son, King of Rome, on 10 June 1811, Napoleon offered the infant’s godmother – his own mother, Madame Mère – this spectacular porcelain fuseau vase (Louvre Museum). The tortoiseshell ground provides a sumptuous setting for a portrait of Napoleon crossing the Alps, after David’s famous painting. The vase is typical of the designs of Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), director of the Sèvres Manufactory, who saw in porcelain a way of giving great history painting imperishable form.

Chronology of Sèvres (below) – an illustrated timeline of works (Cité de la Céramique)

_ 1740 _

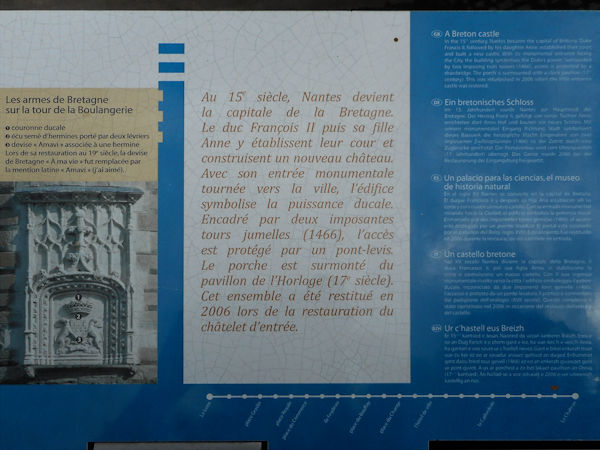

A soft porcelain workshop was founded in Vincennes in a tower of the royal castle, under the reign of Louis XV and the influence of Madame de Pompadour , favorite of the king.

_ 1751 _

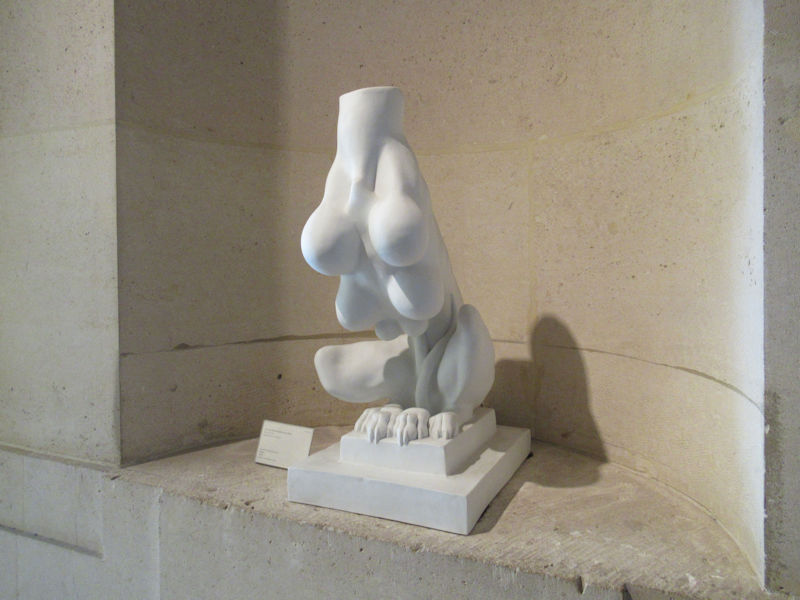

The sculpture is deliberately left in biscuit, without enamel and without decoration, in order to differentiate it from the polychrome production of the Manufacture of Meissen, in Saxony.

_ 1756 _

The Manufacture is transferred to Sèvres in buildings built especially for it, which now house a National Education Service.

_ 1759 _

Louis XV places the Manufacture under the full control of the Crown. It therefore gives it a European influence in the field of porcelain creation.

_ 1768 _

Two researchers from the Manufacture, Pierre-Joseph Macquer and Robert Millot , discover near Limoges the first French kaolin deposit, an essential element of real porcelain, called hard porcelain, marketed as early as 1770.

_ 1800 _

The Manufacture is administered until 1847 by the scientist Alexandre Brongniart , son of the architect of the Paris Stock Exchange, which ensures an exceptional boom.

It was at his initiative that the collection at the origin of the Museum’s creation was born in 1802.

_ 1824 _

The Ceramic and Glass Museum is inaugurated, the first museum exclusively devoted to ceramics and fire arts, both for educational and technical purposes.

Denis-Désiré Riocreux , painter at the Manufacture, becomes the first curator.

_ 1844 … 1845 _

Alexandre Brongniart publishes his Traité des arts ceramiques or potteries considered in their history, their practice and their theory .

The following year, with Riocreux, he wrote a Methodical Description of the Ceramic Museum of the Royal Porcelain Factory of Sèvres , which became the first catalog of the Museum.

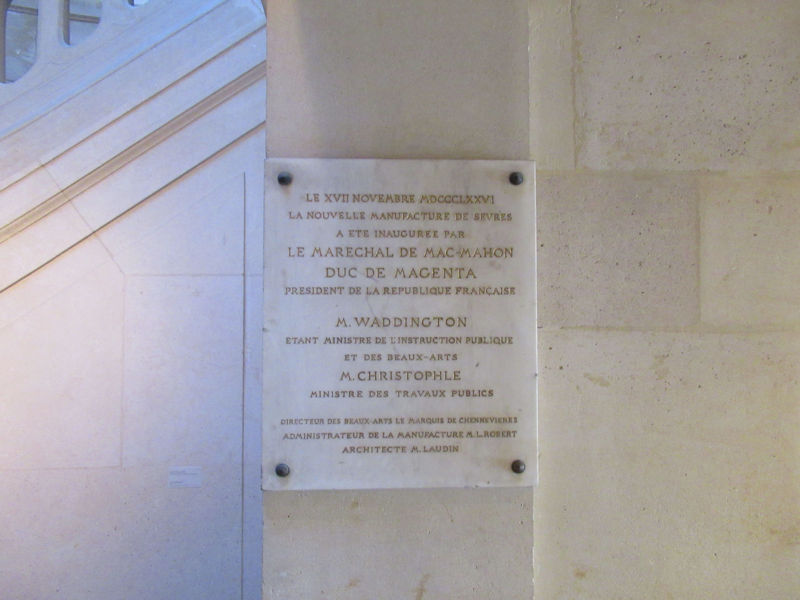

_ 1876 _

With the Third Republic, the Manufacture and the Museum are transferred to buildings specially built by the State on a four-hectare site opened in the park of Saint-Cloud, which they still occupy today.

_ 1900 … 1937 _

The Manufacture’s activities revolve around major international and international exhibitions such as 1900, the Universal Exhibition in Paris, 1925 that of Decorative Arts and, in 1937, the international exhibition of arts and techniques.

Georges Lechevallier-Chevignard , director from 1920 to 1938, obtained in 1927 financial autonomy for the Manufacture, while the Museum is attached to the conservation of the Louvre Museum, in 1934.

_ 1963 _

Henry-Pierre Fourest , curator of the National Museum of Ceramics, achieved a true renaissance of the Museum; In addition to the opening of many rooms, he publishes the Cahiers de la Ceramique and organizes important exhibitions.

_ 1964 … 1975 _

The activity of the Manufacture radically begins the turn of modernity, which invests the entire production, under the direction of Serge Gauthier .

_ 1979 … 1999 _

The opening of eight new rooms on the ground floor devoted to the ceramics of the East and West of the origins in the sixteenth century, complete the presentation on the first floor of faience and European porcelain from the sixteenth century to ‘today, in the Museum.

The restoration of the Salon d’honneur makes it possible to present a unique collection of Sèvres vases from the 19th and 20th centuries.

_ Today _

Porcelain production has returned to the most contemporary creation of the 21st century. From the beginning, visual artists and designers – from Boucher, Duplessis, Falconet in the 18th century, Carrier-Belleuse, Rodin in the 19th century, to Ruhlmann in the 1930s, Decoeur, Mayodon, Calder, Poliakoff in the 50s and 60s, and more recently Pierre Alechinsky, Zao Wou-ki, Jean-Luc Vilmouth, Borek Sipek, Louise Bourgeois, Ettore Sottsass, Bertrand Lavier, Pierre Soulages, Pierre Charpin, Christian Biecher have enriched the repertoire of forms and decorations in Sèvres.

The Museum’s collections have grown considerably, especially for the contemporary period, thanks to a dynamic acquisition policy. Today, more than 50,000 works are preserved.

![]() Or over the centuries:

Or over the centuries:

> 18th century – The rise, the success

> 19th century – Development, research

> 20th century – Between creations and reissues

> 21st century – The way of the contemporary

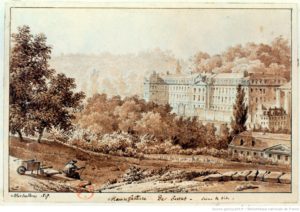

Manufacture de Sèvres, by Achille-Etna Michallon, 1819

The vast and diverse production of the Sèvres factory in the nineteenth century resists easy characterization, and its history during this period reflects many of the changes affecting French society in the years between 1800 and 1900. Among the remarkable accomplishments of the factory was the ability to stay continuously in the forefront of European ceramic production despite the myriad changes in technology, taste, and patronage that occurred during this tumultuous century.

The factory, which had been founded in the town of Vincennes in 1740 and then reestablished in larger quarters at Sèvres in 1756, became the preeminent porcelain manufacturer in Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. Louis XV had been an early investor in the fledgling ceramic enterprise and became its sole owner in 1759. However, due to the upheavals of the French Revolution, its financial position at the beginning of the nineteenth century was extremely precarious. No longer a royal enterprise, the factory also had lost much of its clientele, and its funding reflected the ruinous state of the French economy.

Sèvres (Exhibition Review – Burlington Magazine)

by ROSALIND SAVILL

The inspirational exhibition La Manufacture des Lumières: la sculpture à Sèvres de Louis XV à la Révolution at Sèvres Cité de la Céramique (closed 18th January), set out to prove that porcelain figures are not mere decorative whimsy but significant works of sculpture worthy of serious study. This is fighting spirit, understood by those who work in the field of porcelain, but less recognised by those who do not.  Perhaps this is to be expected when so often the products of porcelain factories are associated with day-to-day domestic life, their sculptures relegated to mere decoration rather than seen as works of art in their own right. This may be inevitable when many were originally intended to replace the sugar figures used to decorate the dessert table but which, because of their hydroscopic nature, tended to melt into a sticky mess. Crisp, fired porcelain, with a glossy glaze and often coloured, was a brilliant and lasting alternative. But, as was seen in this exhibition, this was just the beginning of a story that developed into an extraordinary, innovative and surprising partnership between the fine and decorative arts in eighteenth-century France.

Perhaps this is to be expected when so often the products of porcelain factories are associated with day-to-day domestic life, their sculptures relegated to mere decoration rather than seen as works of art in their own right. This may be inevitable when many were originally intended to replace the sugar figures used to decorate the dessert table but which, because of their hydroscopic nature, tended to melt into a sticky mess. Crisp, fired porcelain, with a glossy glaze and often coloured, was a brilliant and lasting alternative. But, as was seen in this exhibition, this was just the beginning of a story that developed into an extraordinary, innovative and surprising partnership between the fine and decorative arts in eighteenth-century France.

Les Nymphs à la Coquille Jean-Claude Duplessis, c1762

Le Repos de Chasse Etienne-Maurice Falconet after Francois Boucher, 1766

Étienne-Maurice Falconet (Encyclopedia Britannica), (born Dec. 1, 1716, Paris—died Jan. 24, 1791, Paris), was sculptor who adapted the classical style of the French Baroque to an intimate and decorative Rococo ideal. He was patronized by Mme de Pompadour and is best known for his small sculptures on mythological and genre themes and for the designs he made for the Sèvres porcelain factory.

Falconet was a pupil of the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne. He was received in the French Royal Academy in 1754 and soon after began to enjoy royal and official patronage. In 1757 Mme de Pompadour appointed Falconet director of the sculpture studios at the Sèvres porcelain factory. While director, he executed many models for the factory and produced small sculptures of mythological figures, such as Venus and Cupid, and a series of nude female bathers. He also executed a few monumental and religious works. In 1766 he was summoned to Russia by Catherine II at the suggestion of his friend Denis Diderot to produce a bronze equestrian statue of Peter the Great for St. Petersburg. The resulting work, dedicated in 1782, is one of the most powerful and original equestrian portraits of the age. Falconet left Russia in 1778, and, soon after, he suffered a debilitating stroke that left him unable to sculpt.

He is also remembered for his writings, including Réflexions sur la sculpture (1760; “Reflections on Sculpture”), produced at Diderot’s request for the Encyclopédie.

Click Refresh to view slides

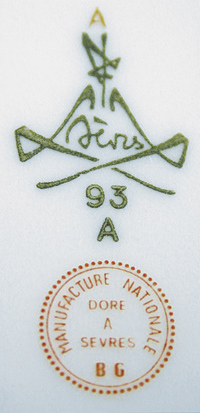

Need to authenticate a Sèvres article?

Want to buy a piece of Sèvres?

Visit the Sèvres workshops – Cité de la Céramique at 2 place de la Manufacture – 92310 Sèvres

Email : visite@sevresciteceramique.fr – Tel. : +33 (0) 1 46 29 22 05