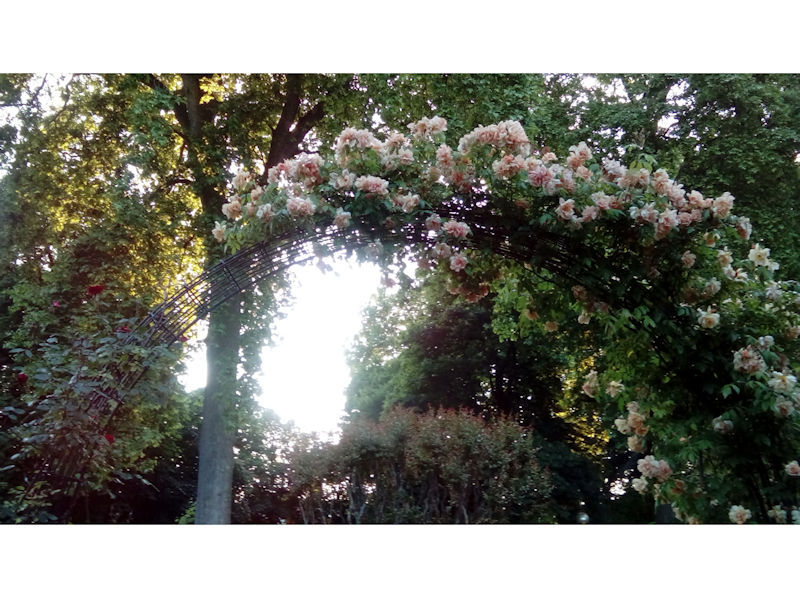

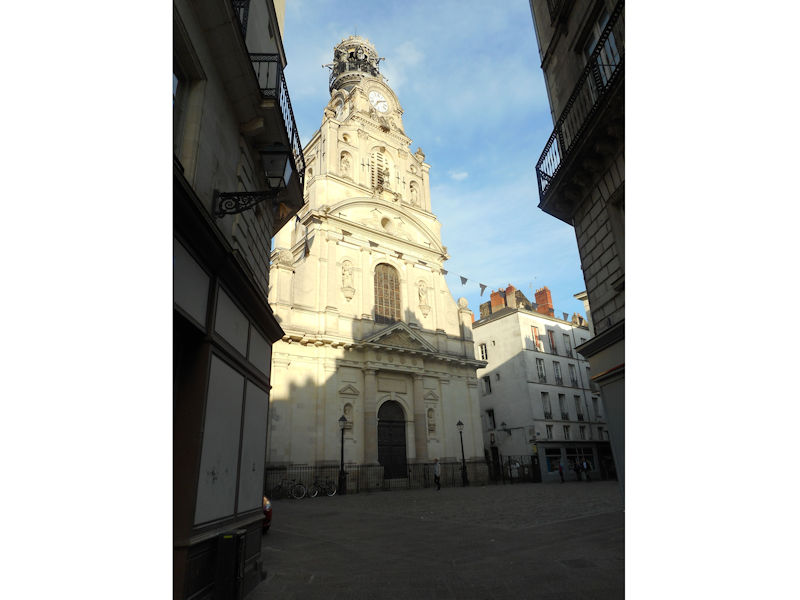

Rue Jeanne d’Arc and the Saint-Croix Cathedral

Rue Jeanne d’Arc and the Saint-Croix Cathedral

In one of the most beautiful Renaissance buildings in the city of Orléans is the Musée historique et archéologique de l’Orléanais. As is to be expected of a regional museum much of what is on display is the history of the Orléans area. Undoubtedly, the most spectacular feature is an exhibition of Gallic and Roman bronzes. The collection consists of 30 bronze objects. They were found in the Neuvy-en-Sullias commune about 30kms from Orlèans. In 1861 the objects were found quite fortuitously by workmen in a sand quarry, but the exact circumstances of their recovery are unclear. The hoard includes various animal, human and mythological figures. From Archaeology Travel

In one of the most beautiful Renaissance buildings in the city of Orléans is the Musée historique et archéologique de l’Orléanais. As is to be expected of a regional museum much of what is on display is the history of the Orléans area. Undoubtedly, the most spectacular feature is an exhibition of Gallic and Roman bronzes. The collection consists of 30 bronze objects. They were found in the Neuvy-en-Sullias commune about 30kms from Orlèans. In 1861 the objects were found quite fortuitously by workmen in a sand quarry, but the exact circumstances of their recovery are unclear. The hoard includes various animal, human and mythological figures. From Archaeology Travel

From Wikipedia

Prehistory and Roman Empire

Cenabum was a Gallic stronghold, one of the principal towns of the tribe of the Carnutes where the Druids held their annual assembly. The Carnutes were massacred and the city was destroyed by Julius Caesar in 52 BC, then a new city was built on its ruins under the Roman Empire. The emperor Aurelian possibly built urbs Aurelianorum, or civitas Aurelianorum, “city of the Aurelii” (cité des Auréliens), which evolved into Orléans.

In 442 Flavius Aetius, the Roman commander in Gaul, requested Goar, head of the Iranian tribe of Alans in the region to come to Orleans and control the rebellious natives and the Visigoths. Accompanying the Vandals, the Alans crossed the Loire in 408. One of their groups, under Goar, joined the Roman forces of Flavius Aetius to fight Attila when he invaded Gaul in 451, taking part in the Battle of Châlons under their king Sangiban. Goar established his capital in Orléans. His successors later took possession of the estates in the region between Orléans and Paris. Installed in Orléans and along the Loire, they were unruly (killing the town’s senators when they felt they had been paid too slowly or too little) and resented by the local inhabitants. Many inhabitants around the present city have names bearing witness to the Alan presence – Allaines. Also many places in the region bear names of Alan origin.

Early Middle Ages

In the Merovingian era, the city was capital of the Kingdom of Orléans following Clovis I’s division of the kingdom, then under the Capetians it became the capital of a county then duchy held in appanage by the house of Valois-Orléans. The Valois-Orléans family later acceded to the throne of France via Louis XII then Francis I. In 1108, one of the few consecrations of a French monarch to occur outside of Reims occurred at Orléans, when Louis VI of France was consecrated in Orléans cathedral by Daimbert, archbishop of Sens.

High Middle Ages

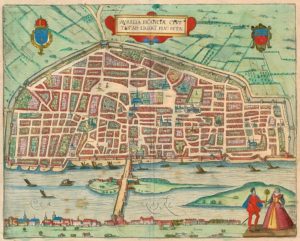

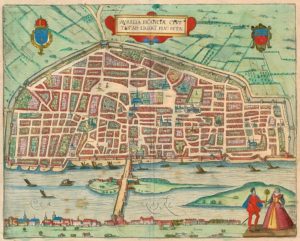

Orléans in September 1428, the time of the Siege of Orléans.

Orléans in September 1428, the time of the Siege of Orléans.

The city was always a strategic point on the Loire, for it was sited at the river’s most northerly point, and thus its closest point to Paris. There were few bridges over the dangerous river Loire, but Orléans had one of them, and so became – with Rouen and Paris – one of medieval France’s three richest cities.

15th-century depiction of the French troops attacking an English fort at the siege of Orléans

On the south bank the “châtelet des Tourelles” protected access to the bridge. This was the site of the battle on 8 May 1429 which allowed Joan of Arc to enter and lift the siege of the Plantagenets during the Hundred Years’ War, with the help of the royal generals Dunois and Florent d’Illiers. The city’s inhabitants had continued to remain faithful and grateful to her to this day, calling her “la pucelle d’Orléans” (the maid of Orléans), offering her a middle-class house in the city, and contributing to her ransom when she was taken prisoner.

Aurelia Franciae civitas ad Ligeri flu. sita (1581)

Once the Hundred Years’ War was over, the city recovered its former prosperity. The bridge brought in tolls and taxes, as did the merchants passing through the city. King Louis XI also greatly contributed to its prosperity, revitalising agriculture in the surrounding area (particularly the exceptionally fertile land around Beauce) and relaunching saffron farming at Pithiviers. Later, during the Renaissance, the city benefited from its becoming fashionable for rich châtelains to travel along the Loire valley (a fashion begun by the king himself, whose royal domains included the nearby châteaus at Chambord, Amboise, Blois, and Chenonceau).

The University of Orléans also contributed to the city’s prestige. Specializing in law, it was highly regarded throughout Europe. John Calvin was received and accommodated there (and wrote part of his reforming theses during his stay), and in return Henry VIII of England (who had drawn on Calvin’s work in his separation from Rome) offered to fund a scholarship at the university. Many other Protestants were sheltered by the city. Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, better known by his pseudonym Molière, also studied law at the University, but was expelled for attending a carnival contrary to university rules.

The Renaissance Hôtel Groslot

From 13 December 1560 to 31 January 1561, the French States-General after the death of Francis II of France, the eldest son of Catherine de Médicis and Henry II. He died in the Hôtel Groslot in Orléans, with his queen Mary at his side.

The cathedral was rebuilt several times. The present structure had its first stone laid by Henry IV, and work on it took a century. It thus is a mix of late Renaissance and early Louis XIV styles, and one of the last cathedrals to be built in France.

1700–1900

When France colonised America, the territory it conquered was immense, including the whole Mississippi River (whose first European name was the River Colbert), from its mouth to its source at the borders of Canada. Its capital was named la Nouvelle-Orléans in honour of Louis XV’s regent, the duke of Orléans, and was settled with French inhabitants against the threat from British troops to the north-east.

The Dukes of Orléans hardly ever visited their city since, as brothers or cousins of the king, they took such a major role in court life that they could hardly ever leave. The duchy of Orléans was the largest of the French duchies, starting at Arpajon, continuing to Chartres, Vendôme, Blois, Vierzon, and Montargis. The duke’s son bore the title duke of Chartres. Inheritances from great families and marriage alliances allowed them to accumulate huge wealth, and one of them, Philippe Égalité, is sometimes said to have been the richest man in the world at the time. His son, Louis-Philippe I, inherited the Penthièvre and Condé family fortunes.

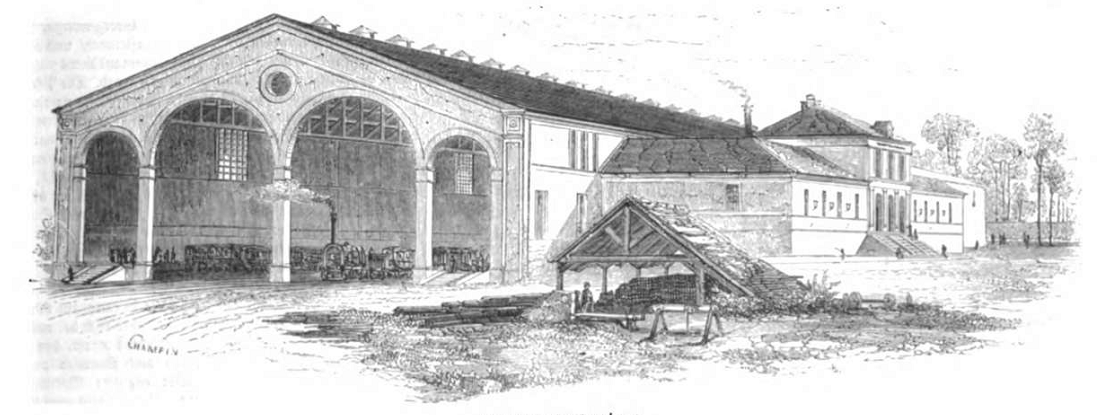

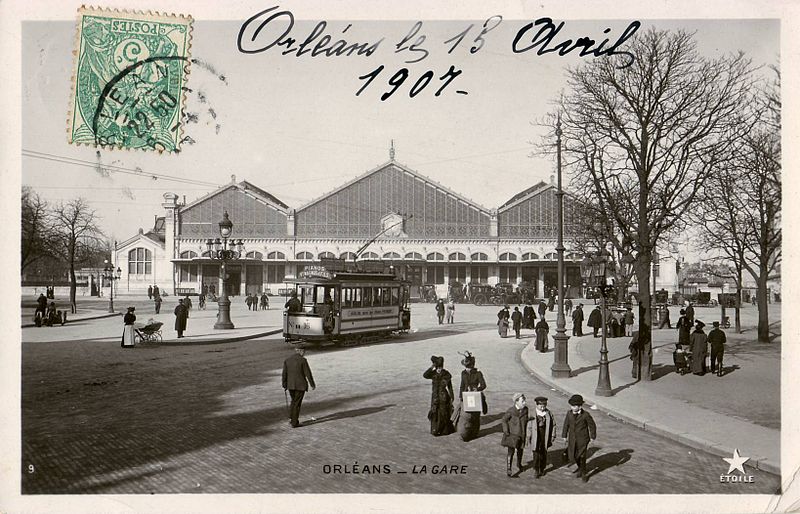

1852 saw the creation of the Compagnies ferroviaires Paris-Orléans and its famous gare d’Orsay in Paris. In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the city again became strategically important thanks to its geographical position, and was occupied by the Prussians on 13 October that year. The armée de la Loire was formed under the orders of General d’Aurelle de Paladines and based itself not far from Orléans at Beauce.

1900 to present

US Army medics in Orléans, 1944

During the Second World War, the German army made the Orléans Fleury-les-Aubrais railway station one of their central logistical rail hubs. The Pont Georges V was renamed “pont des Tourelles”. A transit camp for deportees was built at Beaune-la-Rolande. During the Liberation, the American Air Force heavily bombed the city and the train station, causing much damage. The city was one of the first to be rebuilt after the war: the reconstruction plan and city improvement initiated by Jean Kérisel and Jean Royer was adopted as early as 1943, and work began as early as the start of 1945. This reconstruction in part identically reproduced what had been lost, such as Royale and its arcades, but also used innovative prefabrication techniques, such as îlot 4 under the direction of the architect Pol Abraham.

The big city of former times is today an average-sized city of 250,000 inhabitants. It is still using its strategically central position less than an hour from the French capital to attract businesses interested in reducing transport costs.

Heraldry

According to Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun in La France Illustrée, 1882, Orléans’s arms are “gules, three caillous in cœurs de lys argent, and on a chief azure, three fleurs de lys.

-

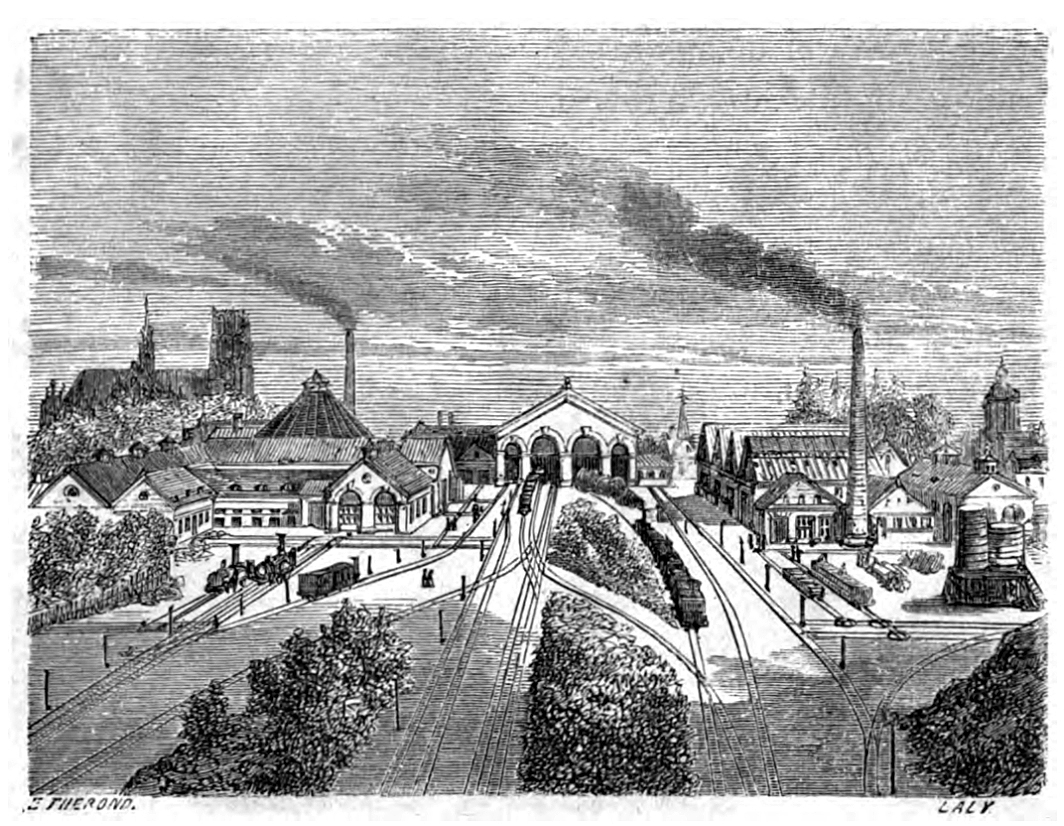

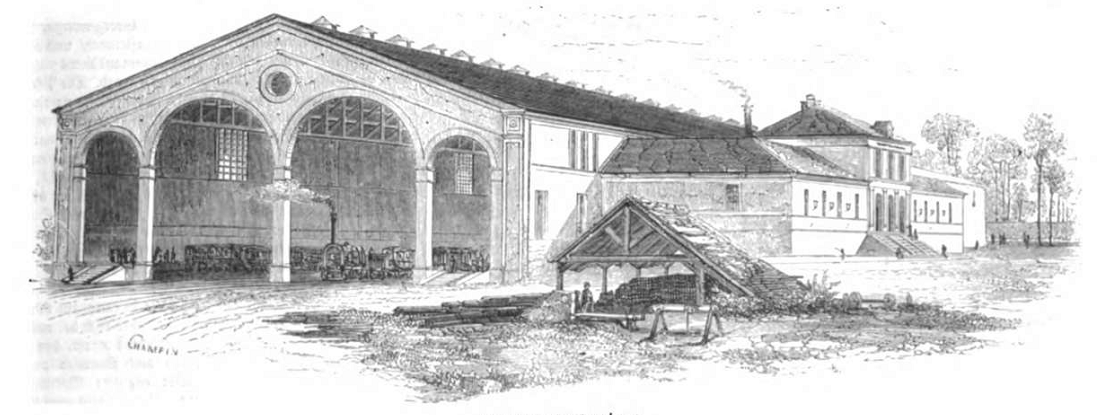

The first station, around 1843

-

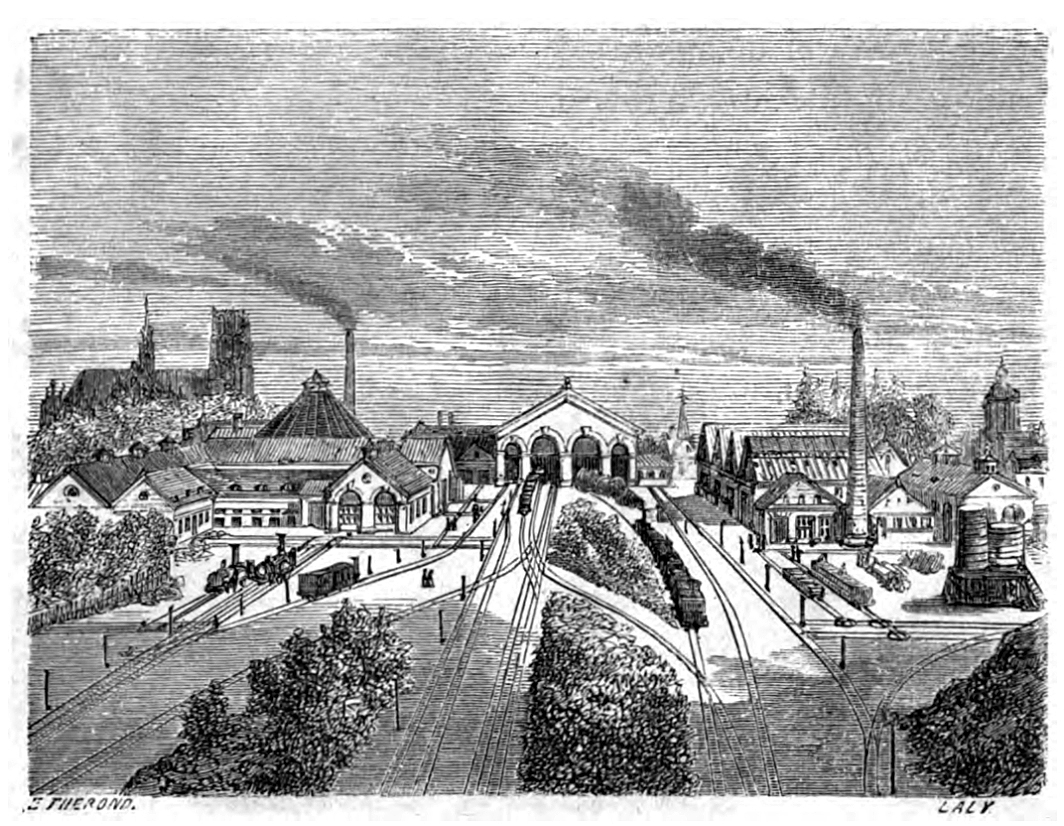

The first station around 1855

-

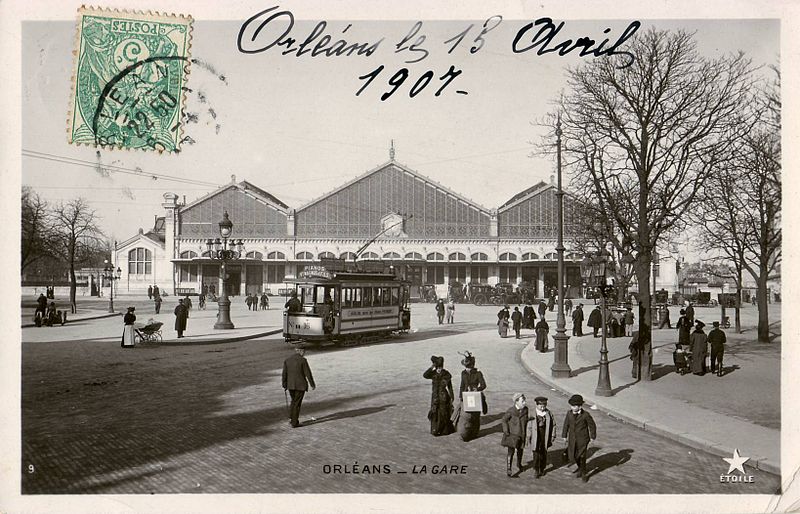

The second station at the beginning of the 20th Century

-

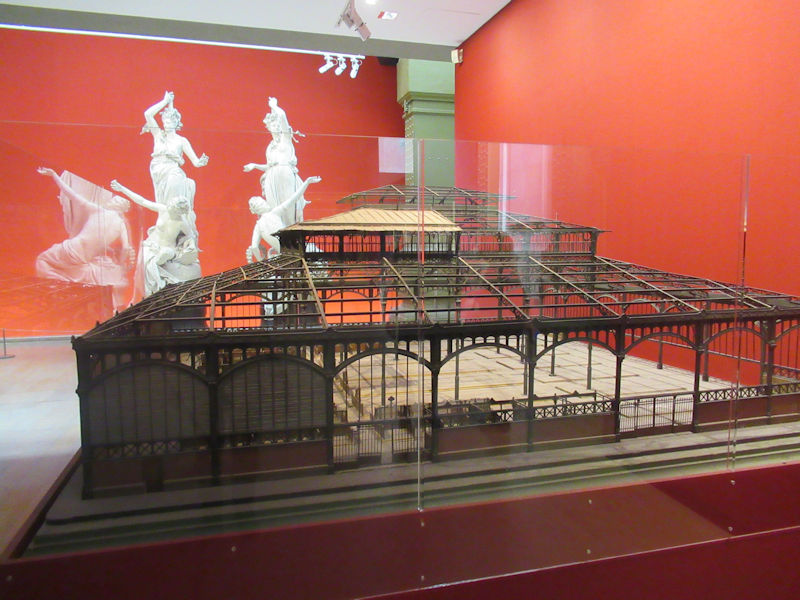

The second station in the 1930s

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

Wikipedia

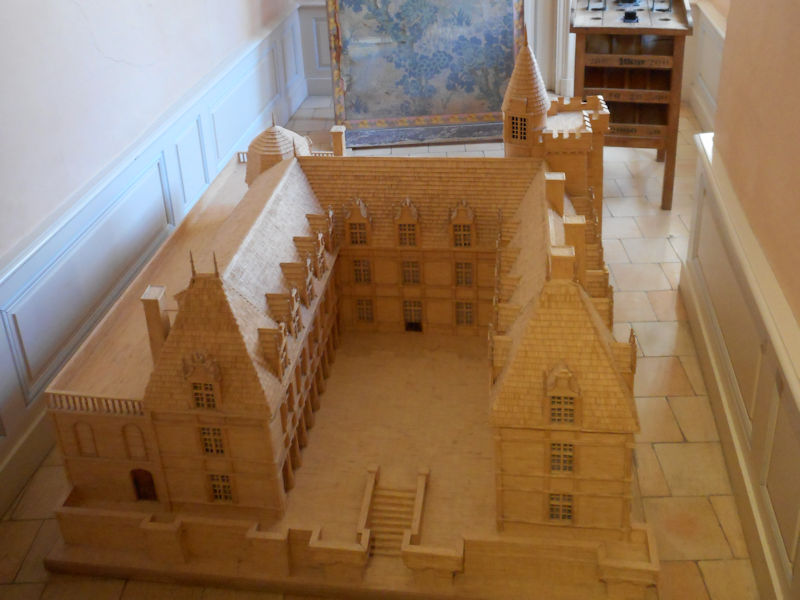

View of the château by Roger de Gaignières, 1705. Paris, French National Library, d’Estampes section.

View of the château by Roger de Gaignières, 1705. Paris, French National Library, d’Estampes section.

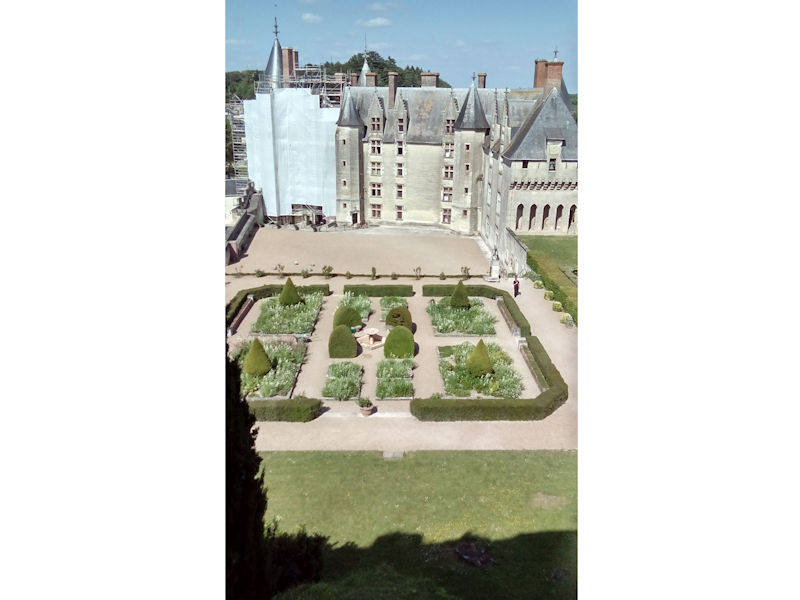

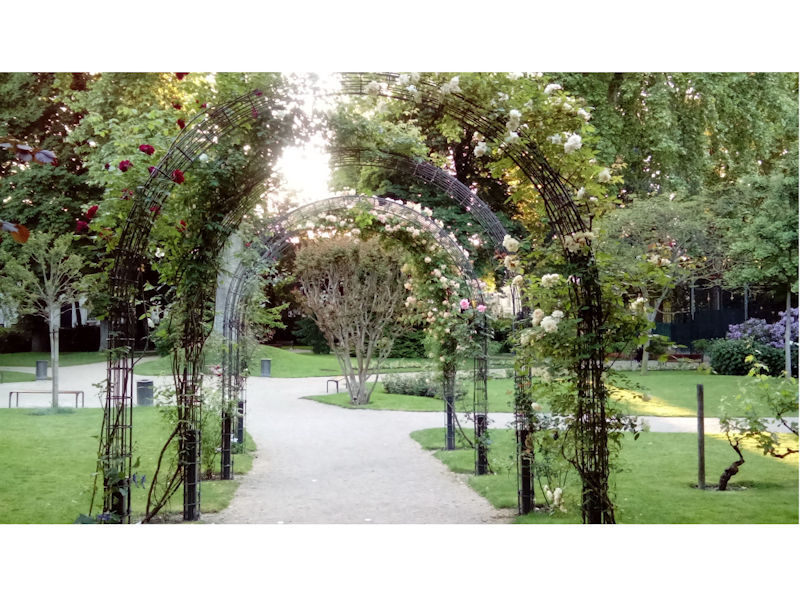

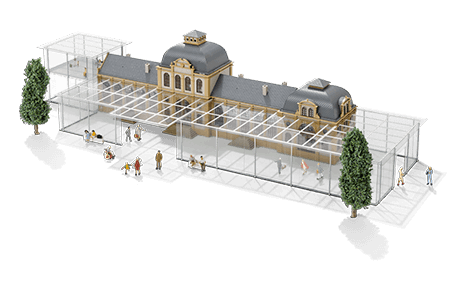

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo

The king considered regulating the flow of the river across the entire estate and diverting some of the water from the Loire, just a few miles away from the site, to the château. These projects, however, never came to pass. There is therefore no [known] project for creating a Renaissance garden at Chambord during the time of Francis I. However, illustrations show the existence of a small garden enclo sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

sed with a palisade close to the monument off the Chapel wing. It was likely an erstwhile vegetable garden, belonging to the former château of the Counts of Blois or an old priory. Finally, a 17th-century diagram shows traces of a previous, larger garden on the northeast side whose design and purpose are difficult to determine.

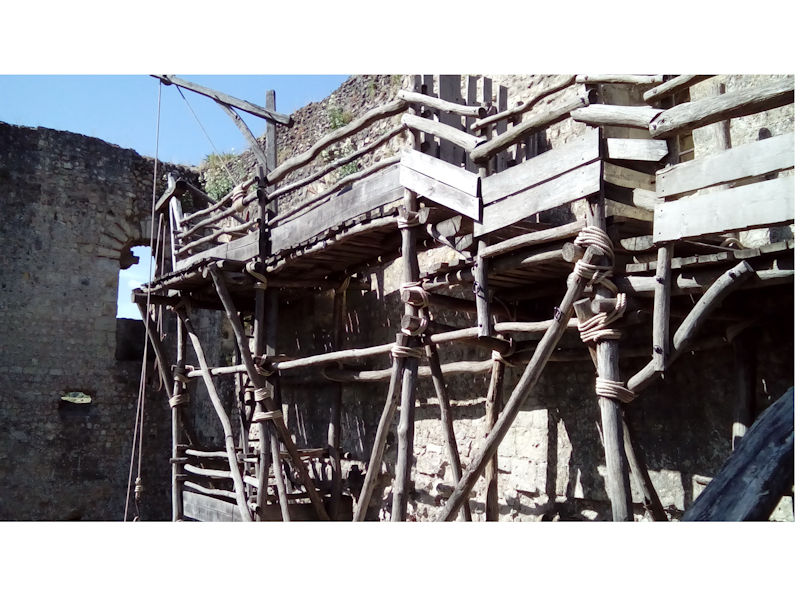

Under the Plantagenet kings, the château was fortified and expanded by Richard I of England (King Richard the Lionheart). However, King Philippe II of France recaptured the château in 1206. Eventually though, during the Hundred Years’ War, the English destroyed it. The château was rebuilt about 1465 during the reign of King Louis XI. The great hall of the château was the scene of the marriage of Anne of Brittany to King Charles VIII on December 6, 1491 that made the permanent union of Brittany and France.

Under the Plantagenet kings, the château was fortified and expanded by Richard I of England (King Richard the Lionheart). However, King Philippe II of France recaptured the château in 1206. Eventually though, during the Hundred Years’ War, the English destroyed it. The château was rebuilt about 1465 during the reign of King Louis XI. The great hall of the château was the scene of the marriage of Anne of Brittany to King Charles VIII on December 6, 1491 that made the permanent union of Brittany and France.