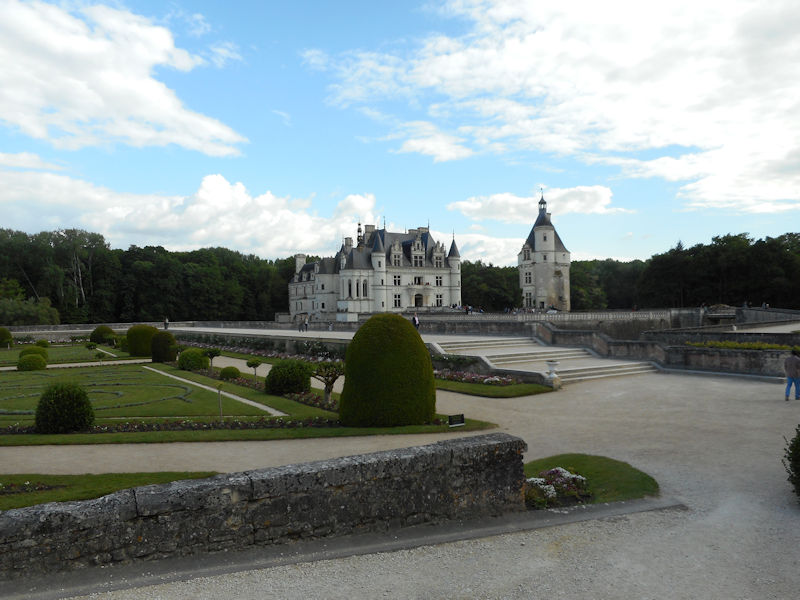

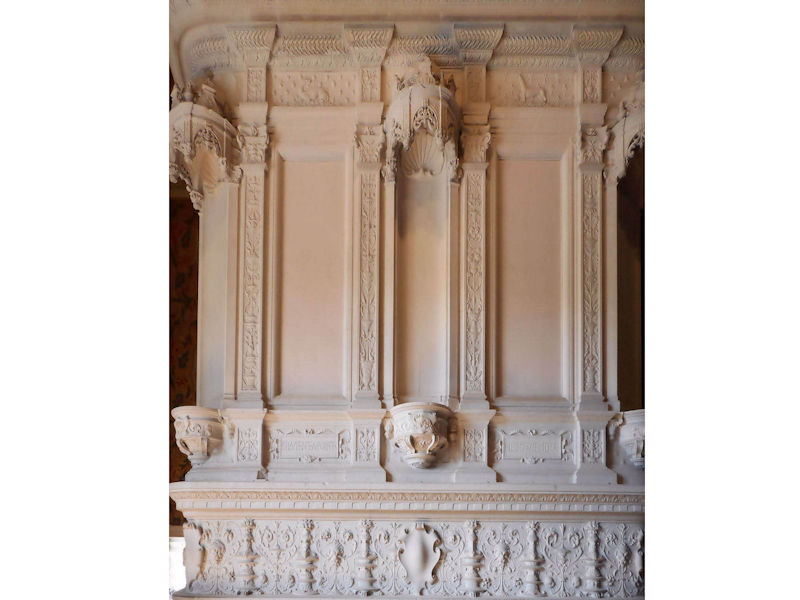

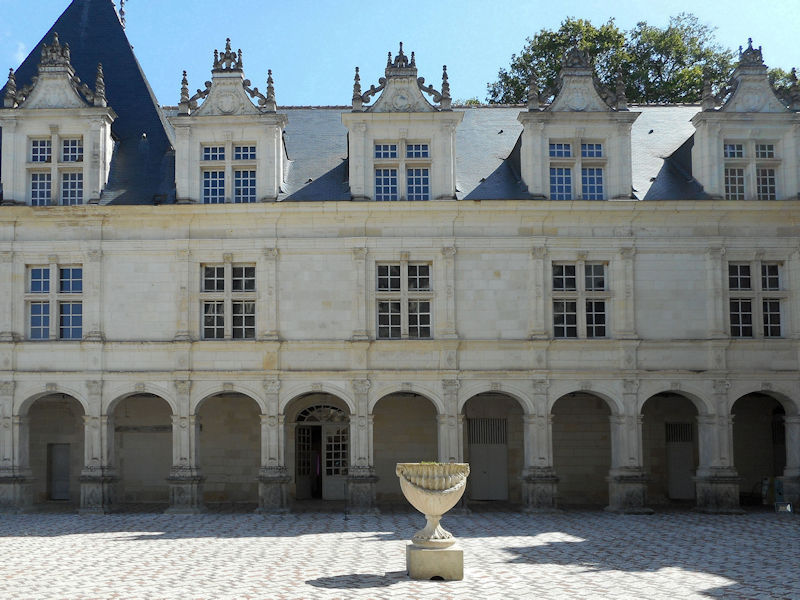

The Château de Chenonceau is a château spanning the River Cher, near the small village of Chenonceaux in the Indre-et-Loire département of the Loire Valley in France. It is one of the best-known châteaux of the Loire valley. The estate of Chenonceau is first mentioned in writing in the 11th century. In the 13th century, the fief of Chenonceau belonged to the Marques family. The original château was torched in 1412 to punish owner Jean Marques for an act of sedition. He rebuilt a château and fortified mill on the site in the 1430s however Jean Marques’s indebted heir Pierre Marques found it necessary to sell. Thomas Bohier, Chamberlain to King Charles VIII of France, purchased the castle from Pierre Marques in 1513 (leading to 2013 being considered the 500th anniversary of the castle: MDXIII–MMXIII.) Bohier demolished the castle, though its 15th-century keep was left standing, and built an entirely new residence between 1515 and 1521. The work was overseen by his wife Katherine Briçonnet,who delighted in hosting French nobility, including King Francis I on two occasions. The château built on the foundations of an old mill was later extended to span the river. The bridge over the river was built (1556-1559) to designs by the French Renaissance architect Philibert de l’Orme, and the gallery on the bridge, built from 1570–1576 to designs by Jean Bullant.

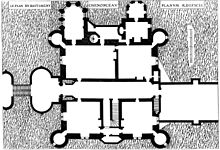

Plan of the main block, engraved by Du Cerceau (1579)

The women of Chenonceau

Diane de Poitiers 1499 – 1566

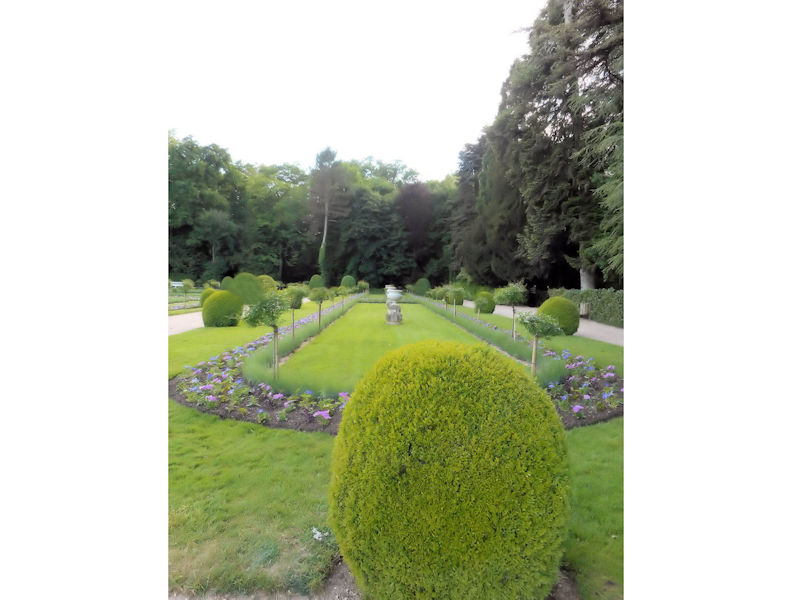

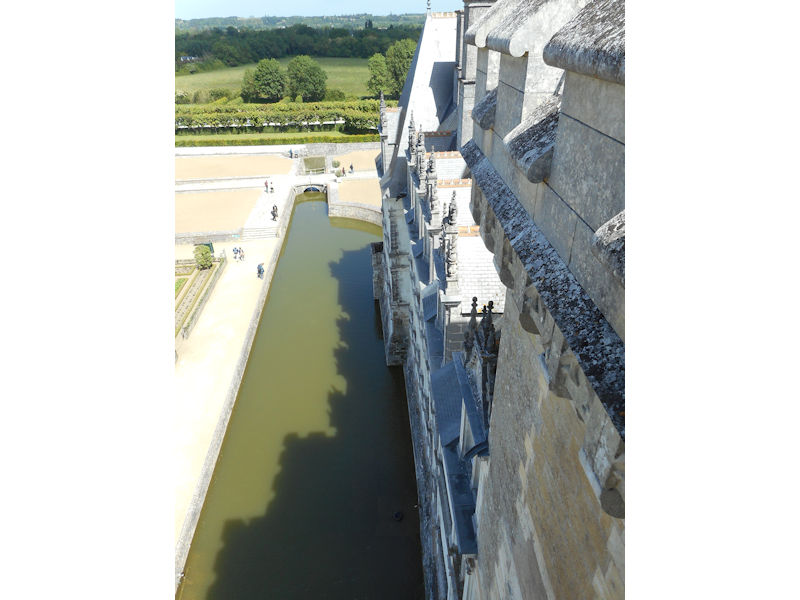

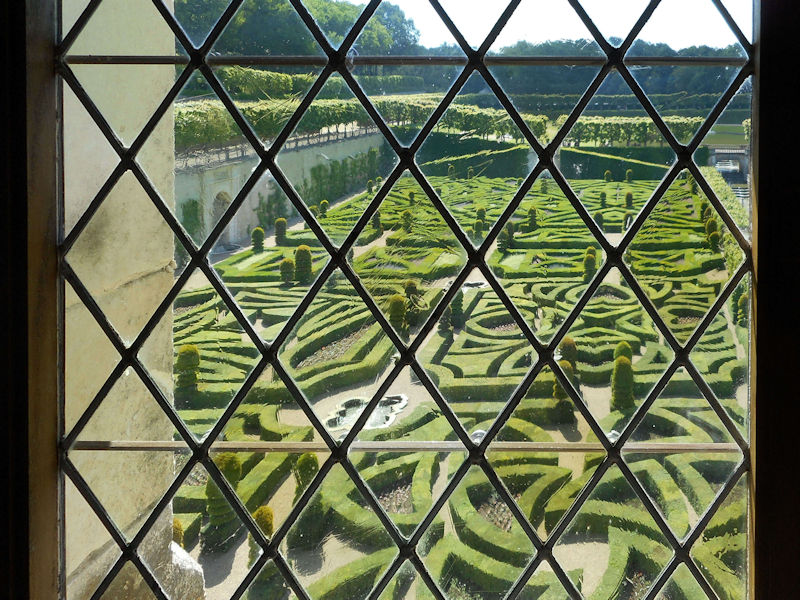

In 1535 the château was seized from Bohier’s son by King Francis I of France for unpaid debts to the Crown; after Francis’ death in 1547, Henry II offered the château as a gift to his mistress, Diane de Poitiers, who became fervently attached to the château along the river. In 1555 she commissioned Philibert de l’Orme to build the arched bridge joining the château to its opposite bank. Diane then oversaw the planting of extensive flower and vegetable gardens along with a variety of fruit trees. Set along the banks of the river, but buttressed from flooding by stone terraces, the exquisite gardens were laid out in four triangles.

Diane de Poitiers was the unquestioned mistress of the castle, but ownership remained with the crown until 1555, when years of delicate legal maneuvers finally yielded possession to her.

Catherine de’ Medici 1519 – 1589

After King Henry II died in 1559, his strong-willed widow and regent Catherine de’ Medici forced Diane to exchange it for the Château Chaumont. Queen Catherine then made Chenonceau her own favorite residence, adding a new series of gardens.

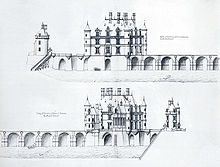

Catherine considered an even greater expansion of the château, shown in an engraving published by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau in the second (1579) volume of his book Les plus excellents bastiments de France. If this project had been executed, the current château would have been only a small portion of an enormous manor laid out “like pincers around the existing buildings.”

Project for the expansion of the château from Du Cerceau’s 1579 book

Louise of Lorraine 1553 – 1601

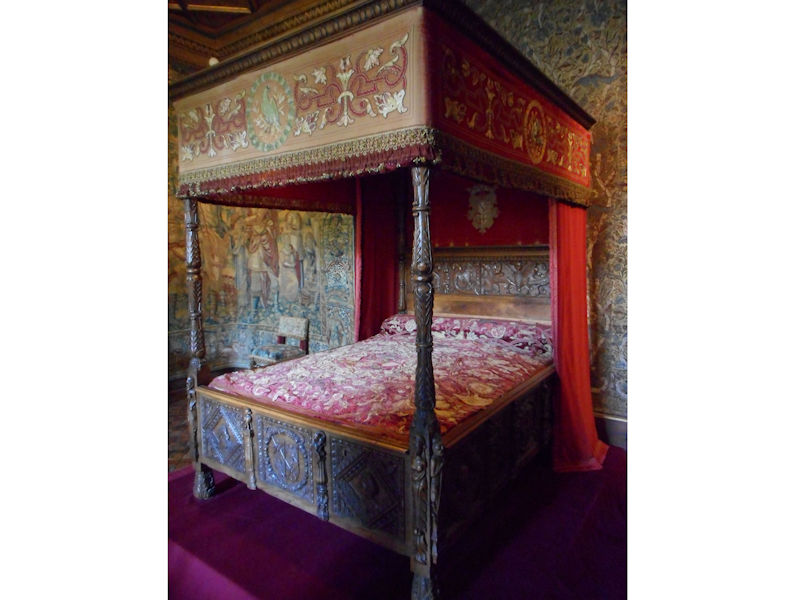

On Catherine’s death in 1589 the château went to her daughter-in-law, Louise de Lorraine-Vaudémont, wife of King Henry III. It was at Chenonceau that Louise was told of her husband’s assassination in 1589. She withdrew to the château and went into mourning, in white, as required by court protocol. Forgotten by all, she had trouble maintaining her queen-dowager life style. She devoted her time to reading, charity work and prayer.

Gabrielle d’Estrées

Henri IV obtained Chenonceau for his mistress Gabrielle d’Estrées by paying the debts of Catherine de’ Medici, which had been inherited by Louise and were threatening to ruin her. In return Louise left the château to her niece Françoise de Lorraine, at that time six years old and betrothed to the four-year-old César de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme, the natural son of Gabrielle d’Estrées and Henri IV. The château belonged to the Duc de Vendôme and his descendants for more than a hundred years. The Bourbons had little interest in the château, except for hunting. In 1650, Louis XIV was the last king of the ancien régime to visit.

The Château de Chenonceau was bought by the Duke of Bourbon in 1720. Little by little, he sold off all of the castle’s contents. Many of the fine statues ended up at Versailles.

Louise Dupin 1706 – 1799

In the 18th century Louise Dupin gave renewed splendor to the château. She started an outstanding salon with the elite among writers, poets, scientists and philosophers, such as Montesquieu, Voltaire or Rousseau. A wise protector of Chenonceau, she managed to save the château during the Revolution.

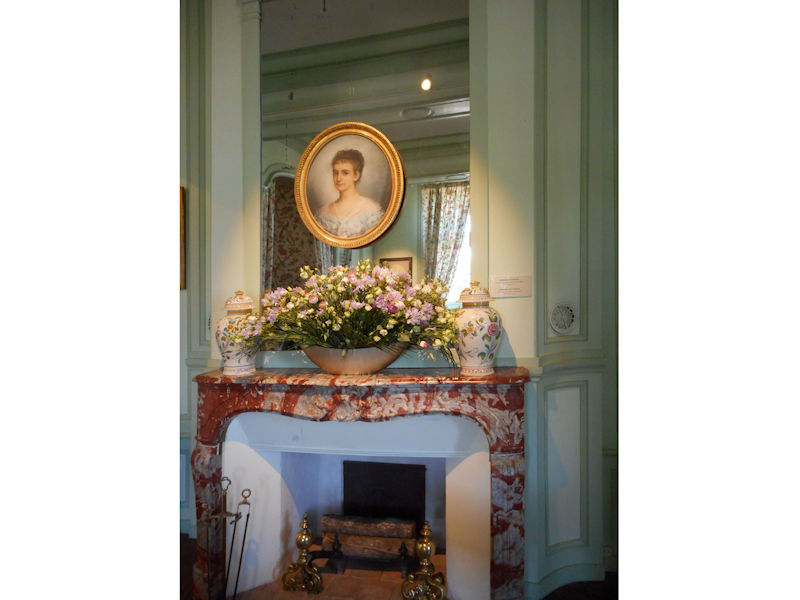

Marguerite Pelouze 1836 – 1902

In the 19th century, Marguerite Pelouze, descended from the industrial bourgeoisie, decided in 1864 to transform the monument and its gardens according to her taste for luxury. She spent a fortune on restoring the estate to the time period of Diane de Poitiers. Chenonceau was sold once, and then again in 1913.

Simonne Menier 1881 – 1972

During the First World War far from the trenches Chenonceau also knew the troubles of wartime. Simone Menier transformed and equipped the gallery into a hospital at her family’s own expense and over 2 000 wounded were cared for up to 1918. Her bravery led her to carry out numerous actions for the resistance during the Second World War (1939-1945).

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

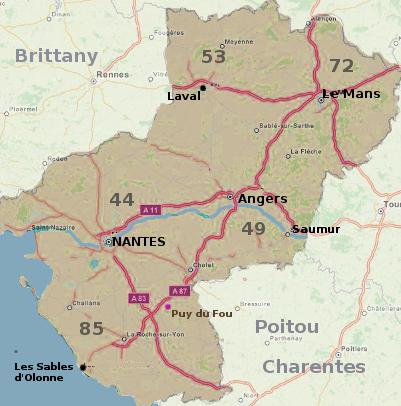

Lying to the southwest of Paris, the Centre region takes in the most visited part of the Loire valley, and areas to the north and to the south. As well as the most popular of the Loire valley chateaux, it also includes the forests of the Sologne, south of the Loire, and the gentle hills and valleys of the Berry region, to the south.

Lying to the southwest of Paris, the Centre region takes in the most visited part of the Loire valley, and areas to the north and to the south. As well as the most popular of the Loire valley chateaux, it also includes the forests of the Sologne, south of the Loire, and the gentle hills and valleys of the Berry region, to the south.