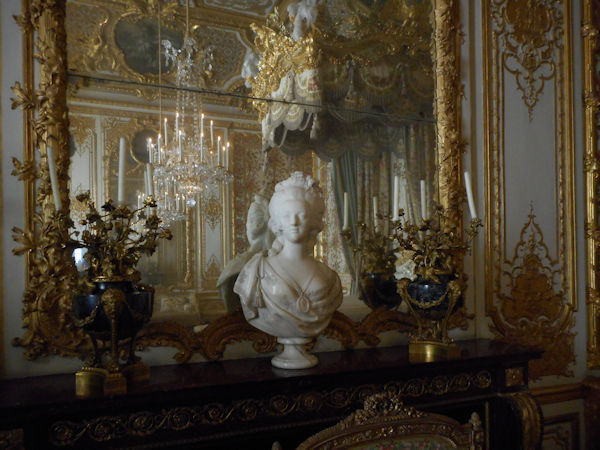

Queens bedroom last modified by Marie Antoinette

From the official website

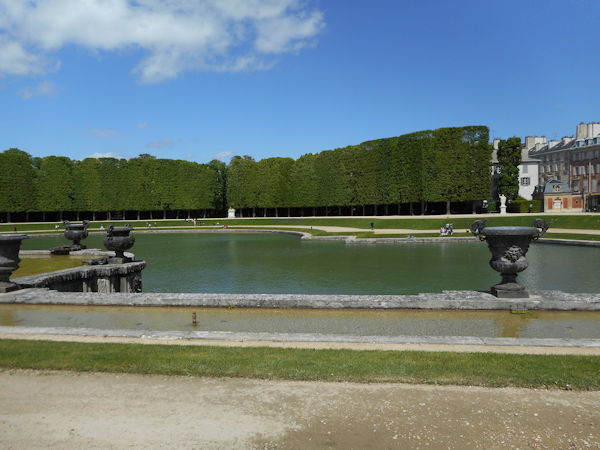

The Palace of Versailles has been listed as a World Heritage Site for 30 years and is one of the greatest achievements in French 17th century art. Louis XIII’s old hunting pavilion was transformed and extended by his son, Louis XIV, when he installed the Court and government there in 1682. A succession of kings continued to embellish the Palace up until the French Revolution.

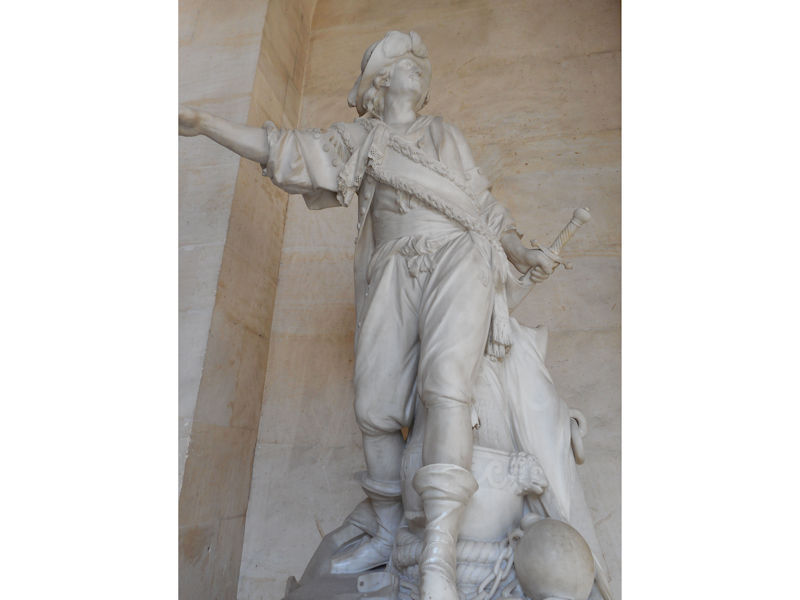

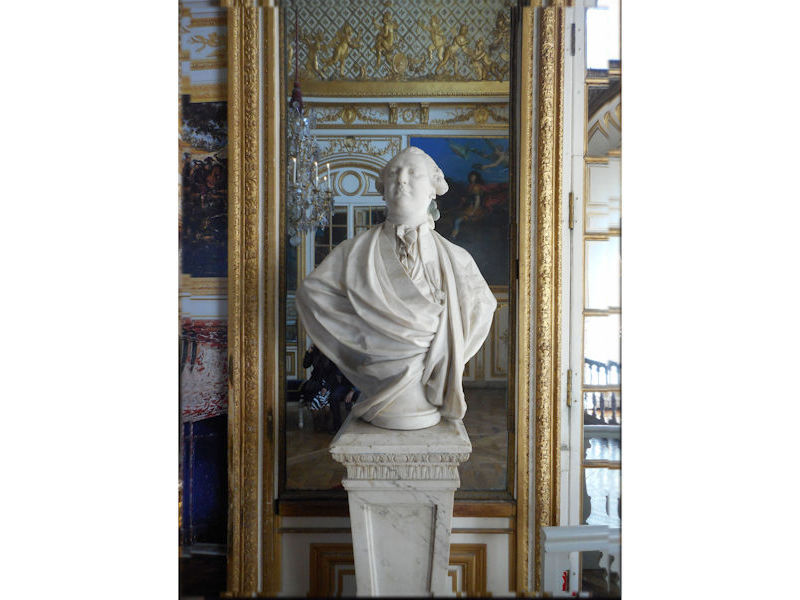

In 1789, the French Revolution forced Louis XVI to leave Versailles for Paris. The Palace would never again be a royal residence and a new role was assigned to it in the 19th century, when it became the Museum of the History of France in 1837 by order of King Louis-Philippe, who came to the throne in 1830. The rooms of the Palace were then devoted to housing new collections of paintings and sculptures representing great figures and important events that had marked the History of France. These collections continued to be expanded until the early 20th century at which time, under the influence of its most eminent curator, Pierre de Nolhac, the Palace rediscovered its historical role when the whole central part was restored to the appearance it had had as a royal residence during the Ancien Régime.

The Palace of Versailles never played the protective role of a medieval stronghold. Beginning in the Renaissance period, the term “chateau” was used to refer to the rural location of a luxurious residence, as opposed to an urban palace. It was thus common to speak of the Louvre “Palais” in the heart of Paris, and the “Château” of Versailles out in the country. Versailles was only a village at the time. It was destroyed in 1673 to make way for the new town Louis XIV wished to create. Currently the centrepiece of Versailles urban planning, the Palace now seems a far cry from the countryside residence it once was. Nevertheless, the garden end on the west side of the Estate of Versailles is still adjoined by woods and agriculture.

CLICK Refresh FOR SLIDES

Madame de Pompadour Royal Mistress and Patron of the Arts (1721-1764)

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour, commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, was a member of the French court and was the official chief mistress of Louis XV from 1745 to 1751, and remained influential as court favourite until her death.

Excerpt..

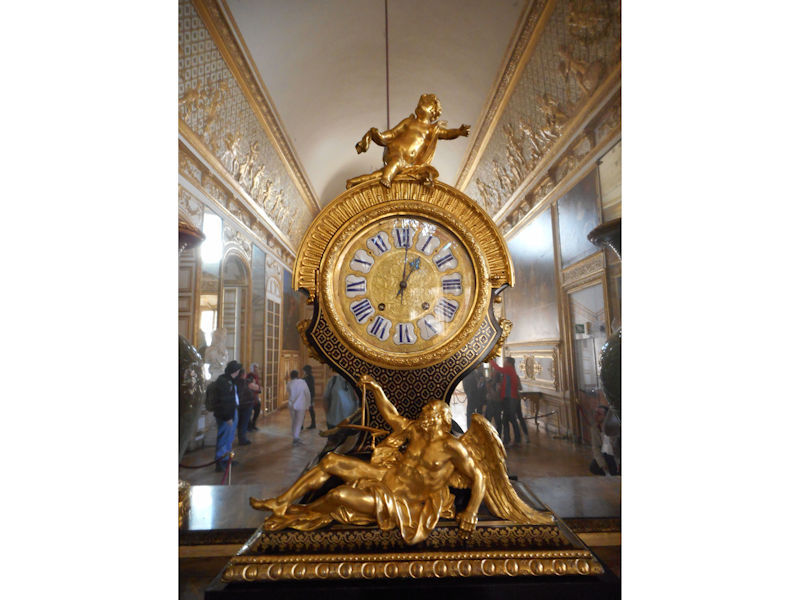

French Decorative Arts During the Reign of Louis XIV: 1654–1715

In 1663, Louis XIV’s future superintendent of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), wrote that the time of private patrons was over: the hour had come for them to yield to the king. To him, and him alone, now belonged the task of steering the intellectual and artistic life of the kingdom. Colbert’s vision for the young Louis XIV (1638–1715), to whom he was to dedicate all his gifts as financial adviser and administrator, strikingly prefigures the development of the arts in France during the long reign of the Sun King , when all the arts would revolve around the king’s personal tastes and will and would reflect the power and splendor of the sovereign and the state. Yet, the prophetic accuracy of Colbert’s statement notwithstanding, no declaration of artistic policy can truly account for the variety, the fantasy, and the brilliant accomplishments of the arts fostered by Louis XIV from 1661, the year he decided to rule France alone (without a prime minister, assisted only by a three-man Privy Council) until his death in 1715.

In 1661, both the taste of the young monarch and prevailing artistic style had already been shaped by the creative fervor of the 1650s. When Louis was anointed king at Reims in 1654, the then-predominant fashion in Paris was the Italian Baroque, so enthusiastically promoted by Cardinal Mazarin (1601–1661), prime minister and godfather to Louis. Italian painters such as Gian Francesco Romanelli were imported by Mazarin to decorate his palace and were recruited to work on the Palais du Louvre. The Royal Apartments and those of the Queen Mother, Anne of Austria, were redecorated in 1654–55 with frescoed and stuccoed ceilings in the Bolognese manner. Romanelli worked side by side with French sculptors—sometimes trained in Italy , like Michel Anguier—in a newfound harmony that recalled the Renaissance traditions of the Fontainebleau of François I (1494–1547) and brought together Italian decorative inventions and French elegance of line and composition.

From the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art based on original work by Olga Raggio,

Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

August 2009

Full article at Metropolitan Museum of Art