Click Refresh to view slides

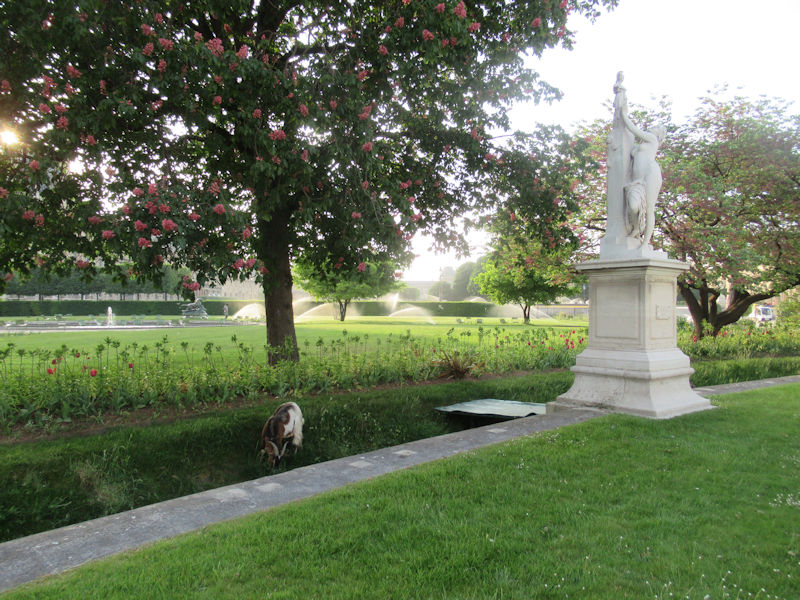

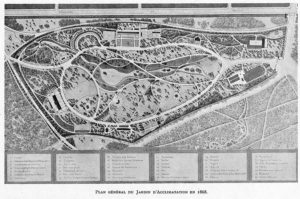

The Tuileries Garden (French: Jardin des Tuileries) is a public garden located between the Louvre Museum and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris. Created by Catherine de’ Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace in 1564, it was eventually opened to the public in 1667 and became a public park after the French Revolution. In the 19th and 20th centuries, it was a place where Parisians celebrated, met, strolled, and relaxed.[1]

History and development

Garden of Catherine de’ Medici

In July 1559, after the accidental death of her husband, Henry II, Queen Catherine de’ Medici decided to leave her residence of the Hôtel des Tournelles, at the eastern part of Paris, near the Bastille. Together with her son, the new king of France François II, her other children and the royal court, she moved to the Louvre Palace. Five years later, in 1664, she commissioned the construction of a new palace just beyond the wall of Charles V, not far from the Louvre, from which it would be separated by a neighborhood of private hotels, churches, convents, and the Hospice des Quinze-Vingts near the Porte Saint-Honoré.

For that purpose, Catherine had bought land west of Paris, on the other side of the portion of the wall of Charles V situated between the Tour du Bois and the 14th century Porte Saint-Honoré. It was bordered on the south by the Seine, and on the north by the faubourg Saint-Honoré, a road in the countryside continuing the rue Saint-Honoré. Since the 13th century this area had been occupied by tile-making fabrics called tuileries (from the French tuile, meaning “tile”).

Catherine further commissioned a landscape architect from Florence, Bernard de Carnesse, to create an Italian Renaissance garden, with fountains, a labyrinth, a grotto, and decorated with faience images of plants and animals, made by Bernard Palissy, whom Catherine had tasked to discover the secret of Chinese porcelain.

The Tuileries Garden in 1615, where the Grand Basin is now located. The covered promenade can be seen, and the riding school established by Catherine.

The garden of Catherine de’ Medici was an enclosed space five hundred metres long and three hundred metres wide, separated from the new palace by a lane. It was divided into rectangular compartments by six alleys, and the sections were planted with lawns, flower beds, and small clusters of five trees, called quinconces; and, more practically, with kitchen gardens and vineyards.[2]

The Tuileries garden was the largest and most beautiful garden in Paris at the time. Catherine used it for lavish royal festivities honoring ambassadors from Queen Elizabeth I of England, and the marriage of her daughter, Marguerite de Valois, to Henri III of Navarre, better known as Henry IV, King of France and of Navarre.[3]

Garden of Henry IV

King Henry III was forced to flee Paris in 1588, and the gardens fell into disrepair. His successor, Henry IV (1589–1610), and his gardener, Claude Mollet, restored the gardens, built a covered promenade the length of the garden, and a parallel alley planted with mulberry trees where he hoped to cultivate silkworms and start a silk industry in France. He also built a rectangular ornamental lake of 65 metres by 45 metres with a fountain supplied with water by the new pump called La Samaritaine, which had been built in 1608 on the Pont Neuf. The area between the palace and the former moat of Charles V was turned into the “New Garden” (Jardin Neuf) with a large fountain in the center. Though Henry IV never lived in the Tuilieries Palace, which was continually under reconstruction, he did use the gardens for relaxation and exercise.

Garden of Louis XIII

The Tuileries Garden in 1652 with the Parterre de Mademoiselle east of the Palace

In 1610, at the death of his father, Louis XIII became the new owner of the Tuileries Gardens at the age of nine. It became his enormous playground – he used it for hunting, and he kept a menagerie of animals. On the north side of the gardens, Marie de’ Medici established a riding school, stables, and a covered manege for exercising horses.

When the king and court were absent from Paris, the gardens were turned into a pleasure spot for the nobility. In 1630 a former rabbit warren and kennel at the west rampart of the garden were made into a flower-lined promenade and cabaret. The daughter of Gaston d’Orléans and the niece of Louis XIII, known as La Grande Mademoiselle, held a sort of court in the cabaret, and the “New Garden” of Henry IV (the present-day Carousel) became known as the “Parterre de Mademoiselle.” In 1652, “La Grande Mademoiselle” was expelled from the chateau and garden for having supported an uprising, the Fronde, against her cousin, the young Louis XIV.[4]

Garden of Louis XIV and Le Nôtre

Tuileries Garden of Le Nôtre in the 17th century, looking west toward the future Champs Élysées, engraving by Perelle

The statue of Renommée, or the fame of the king, riding the horse Pegasus, (1699) by Antoine Coysevox (1640–1720) at the west entrance of the Garden. Originally located on Louis XIV’s estate at Marly, it was moved to the Tuileries in 1719

The new king quickly imposed his own sense of order on the Tuileries Gardens. His architects, Louis Le Vau and François d’Orbay, finally finished the Tuileries Palace, making a proper royal residence. In 1662, to celebrate the birth of his first child, Louis XIV held a vast pageant of mounted courtiers in the New Garden, which had been enlarged by filling in Charles V’s moat and had been turned into a parade ground. Thereafter the square was known as the Place du Carrousel.[5]

In 1664, Colbert, the king’s superintendent of buildings, commissioned the landscape architect André Le Nôtre, to redesign the entire garden. Le Nôtre was the grandson of Pierre Le Nôtre, one of Catherine de’ Medici’s gardeners, and his father Jean had also been a gardener at the Tuileries. He immediately began transforming the Tuileries into a formal garden à la française, a style he had first developed at Vaux-le-Vicomte and perfected at Versailles, based on symmetry, order and long perspectives.

Le Nôtre’s gardens were designed to be seen from above, from a building or terrace. He eliminated the street which separated the palace and the garden, and replaced it with a terrace looking down upon flowerbeds bordered by low boxwood hedges and filled with designs of flowers. In the centre of the flowerbeds he placed three ornamental lakes with fountains. In front of the centre of the first fountain he laid out the Grande Allée, which extended 350 metres. He built two other alleys, lined with chestnut trees, on either side. He crossed these three main alleys with small lanes, to create compartments planted with diverse trees, shrubs and flowers.

On the south side of the park, next to the Seine, he built a long terrace called the Terrasse du bord-de-l’eau, planted with trees, with a view of the river He built a second terrace on the north side, overlooking the garden, called the Terrasse des Feuillants.

On the west side of the garden, beside the present-day Place de la Concorde, he built two ramps in a horseshoe shape and two terraces overlooking an octagonal lake 60 m (200 ft) in diameter with a fountain in the centre. These terraces frame the western entrance of the garden, and provide another viewpoint to see the garden from above.

Le Nôtre wanted his grand perspective from the palace to the western end of the garden to continue outside the garden. In 1667, he made plans for an avenue with two rows of trees on either side, which would have continued west to the present Rond-Point des Champs Élysées.[6]

Le Nôtre and his hundreds of masons, gardeners and earth-movers worked on the gardens from 1666 to 1672. In 1682, however, the king, furious with the Parisians for resisting his authority, abandoned Paris and moved to Versailles.

In 1667, at the request of the famous author of Sleeping Beauty and other fairy tales, Charles Perrault, the Tuileries Garden was opened to the public, with the exception of beggars, “lackeys” and soldiers.[7] It was the first royal garden to be open to the public.

In the 18th century

After the death of Louis XIV, the five-year-old Louis XV became owner of the Tuileries Garden. The garden, abandoned for nearly forty years, was put back in order. In 1719, two large equestrian statuary groups, La Renommée and Mercure, by the sculptor Antoine Coysevox, were brought from the king’s residence at Marly and placed at the west entrance of the garden. Other statues by Nicolas and Guillaume Coustou, Corneille an Clève, Sebastien Slodz, Thomas Regnaudin and Coysevox were placed along the Grande Allée.[8] A swing bridge was placed at the west end over the moat, to make access to the garden easier. The creation of the place Louis XV (now Place de la Concorde) created a grand vestibule to the garden.

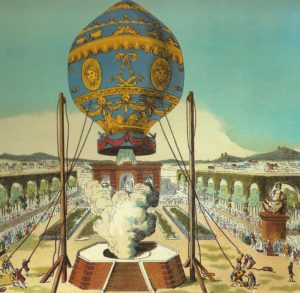

Certain holidays, such as August 25, the feast day of Saint Louis, were celebrated with concerts and fireworks in the park. A famous early balloon ascent was made from the garden on December 1, 1783 by Jacques Alexandre César Charles and Nicolas Louis Robert. Small food stands were placed in the park, and chairs could be rented for a small fee.[9] Public toilets were added in 1780.[10]

During the French revolution

The Tuileries, renamed the “Jardin National” during the French Revolution- the Festival of the Supreme Being (1794)

On October 6, 1789, as the French Revolution began, King Louis XVI was brought against his will to the Tuileries Palace. The garden was closed to the public except in the afternoon. Queen Marie Antoinette and the Dauphin were given a part of the garden for her private use, first at the west end of the Promenade Bord d’eaux, then at the edge of the Place Louis XV.

After the king’s failed attempt to escape France, the surveillance of the family was increased. The royal family was allowed to walk in the park on the evening of September 18, 1791, during the festival organized to celebrate the new French Constitution, when the alleys of the park were illuminated with pyramids and rows of lanterns.[11] On August 10, 1792, a mob stormed the Palace, and the king’s Swiss guards were chased through the gardens and massacred. After the king’s removal from power and execution, the Tuileries became the National Garden (Jardin National) of the new French Republic. In 1794 the new government assigned the renewal of the gardens to the painter Jacques-Louis David, and to his brother in law, the architect August Cheval de Saint-Hubert. They conceived a garden decorated with Roman porticos, monumental porches, columns, and other classical decoration. The project of David and Saint-Hubert was never completed. All that remains today are the two exedres, semicircular low walls crowned with statues by the two ponds in the centre of the garden.[12]

While David’s project was not finished, large numbers of statues from royal residences were brought to the gardens for display. The garden was also used for revolutionary holidays and festivals. On June 8, 1794, a ceremony in honor of the Cult of the Supreme Being was organized in the Tuileries by Robespierre, with sets and costumes designed by Jacques-Louis David. After a hymn written for the occasion, Robespierre set fire to mannequins representing Atheism, Ambition, Egoism and False Simplicity, revealing a statue of Wisdom.[13]

In the 19th century

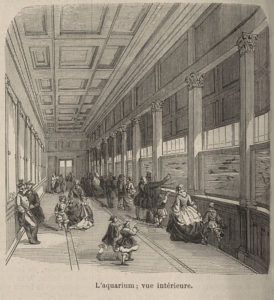

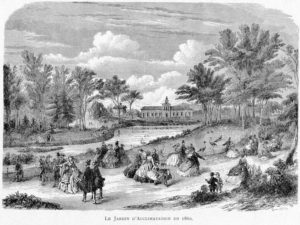

In the 19th century, the Tuileries Garden was the place where ordinary Parisians went to relax, meet, stroll, enjoy the fresh air and greenery, and be entertained.

Napoleon Bonaparte, about to become Emperor, moved into the Tuileries Palace on February 19, 1800, and began making improvements to suit an imperial residence. A new street was created between the Louvre and the Place du Carrousel, a fence closed the courtyard, and he built a small triumphal arch, modeled after the arch of Septimius Severus in Rome, in the middle of the Place du Carrousel, as the ceremonial entrance to his palace.

In 1801 Napoleon ordered the construction of a new street along the northern edge of the Tuileries, through space that had been occupied by the riding school and stables built by Marie de’ Medici, and the private gardens of aristocrats and convents and religious orders that had been closed during the Revolution. This new street also took part of the Terrasse des Feuillants, which had been occupied by cafés and restaurants. The new street, lined with arcades on the north side, was named the rue de Rivoli, after Napoleon’s victory in 1797.

Napoleon made few changes to the interior of the garden. He continued to use the garden for military parades and to celebrate special events, including the passage of his own wedding procession on April 2, 1810, when he married the Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria.

After the fall of Napoleon, the garden briefly became the encampment of the occupying Austrian and Russian soldiers. The monarchy was restored, and the new King, Charles X, renewed an old tradition and celebrated the feast day of Saint Charles in the garden.

In 1830, after a brief revolution, the new king, Louis-Philippe, became owner of the Tuileries. He wanted a private garden within the Tuileries, so a section of the garden in front of the palace was separated by a fence from the rest of the Tuileries. A small moat, flower beds and eight new statues by sculptors of the period decorated the new private garden.

In 1852, following another revolution and the shortlived Second Republic, a new Emperor, Louis Napoleon, became owner of the garden. He enlarged his private reserve within the garden further to the west as far as the north–south alley that crossed the large round basin, so that included the two small round basins. He decorated his new garden with beds of exotic plants and flowers, and new statues. In 1859, he made the Terrasse du bord-de-l’eau into a playground for his son, the Prince Imperial. He also constructed twin pavilions, the Jeu de paume and the Orangerie, at the west end of the garden, and built a new stone balustrade at the west entrance. When The Emperor was not in Paris, usually from May to November, the entire garden, including his private garden and the playground, were open to the public.

In 1870, Emperor Louis Napoleon was defeated and captured by the Prussians, and Paris was the scene of the uprising of the Paris Commune. A red flag flew over the Palace, and it could be visited for fifty centimes. When the army arrived and fought to recapture the city, the Communards deliberately burned the Tuileries Palace, and tried to burn the Louvre as well. The ruins were not torn down until 1883. The empty site of the palace, between the two pavilions of the Louvre, became part of the garden.

In the 20th century

Jardin des Tuileries in winter

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, the Tuilieries garden was filled with entertainments for the public; acrobats, puppet theatres, lemonade stands, small boats on the lakes, donkey rides, and stands selling toys. At the 1900 Summer Olympics, the Gardens hosted the fencing events.[14] The peace in the garden was interrupted by the First World War in 1914; the statues were surrounded by sandbags, and in 1918 two German long-range artillery shells landed in the garden.

In the years between the two World Wars, the Jeu de paume tennis court was turned into a gallery, and its western part was used to display the Water Lilies series of paintings by Claude Monet. The Orangerie became an art gallery for contemporary western art.

During World War II, the Jeu de paume was used by the Germans as a warehouse for art they had stolen or confiscated.

The liberation of Paris in 1944 saw considerable fighting in the garden. Monet’s paintings Water Lilies were seriously damaged during the battle.[15]

Until the 1960s, almost all the sculpture in the garden dated from the 18th or 19th century. In 1964–65, André Malraux, the Minister of Culture for President Charles de Gaulle, removed the 19th century statues which surrounded the Place du Carrousel and replaced them with contemporary sculptures by Aristide Maillol.

In 1994, as part of the Grand Louvre project launched by President François Mitterrand, the Belgian landscape architect Jacques Wirtz remade the garden of the Carrousel, adding labyrinths and a fan of low hedges radiating from the triumphal arch in the square.

In 1998, under President Jacques Chirac, works of modern sculpture by Jean Dubuffet, Henri Laurens, Étienne Martin, Henry Moore, Germaine Richier, Auguste Rodin and David Smith were placed in the garden. In 2000, the works of living artists were added; these included works by Magdalena Abakanowicz, Louise Bourgeois, Tony Cragg, Roy Lichtenstein, François Morrellet, Giuseppe Penone, Anne Rochette and Lawrence Weiner. Another ensemble of three works by Daniel Dezeuze, Erik Dietman and Eugène Dodeigne, called Prière Toucher (Eng: Please Touch), was added at the same time.[16]

In the 21st century

Café de Pomone, Jardin des Tuileries, in springtime

At the beginning of the 21st century, French landscape architects Pascal Cribier and Louis Benech have been working to restore some of the early features of the André Le Nôtre garden.[17]

Areas of special interest

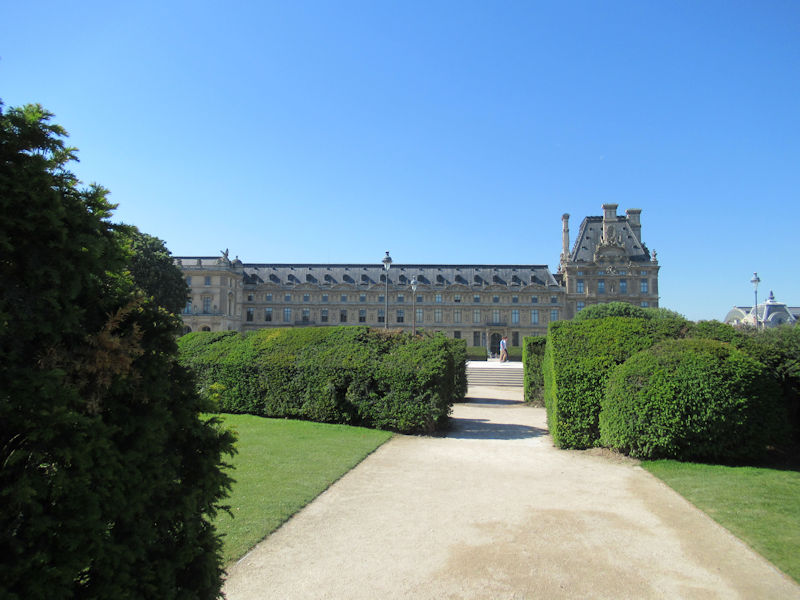

Jardin du Carrousel

Arc de triomphe du Carrousel

Also known as the Place du Carrousel, this part of the garden used to be enclosed by the two wings of the Louvre and by the Tuileries Palace. In the 18th century it was used as a parade ground for cavalry and other festivities. The central feature is the Arc de triomphe du Carrousel, built to celebrate the victories of Napoleon, with bas-relief sculptures of his battles by Jean Joseph Espercieux. The garden was remade in 1995 to showcase a collection of 21 statues by Aristide Maillol, which had been put in the Tuileries in 1964.

Terrasse

The elevated terrace between the Carrousel and the rest of the garden used to be at the front of the Tuileries Palace. After the Palace was burned in 1870, it was made into a road, which was put underground in 1877. The terrace is decorated by two large vases which used to be in the gardens of Versailles, and two statues by Aristide Maillol; the Monument to Cézanne on the north and the Monument aux morts de Port Vendres on the south.

Moat of Charles V

Two stairways descend from the Terrasse to the moat (fr:fossés) named for Charles V of France, who rebuilt the Louvre in the 14th century. It was part of the old fortifications which originally surrounded the palace. On the west side are traces left by the fighting during the unsuccessful siege of Paris by Henry IV of France in 1590 during the French Wars of Religion. Since 1994 the moat has been decorated with statues from the facade of the old Tuileries Palace and with bas-reliefs made in the 19th century during the Restoration of the French monarchy which were meant to replace the Napoleonic bas-reliefs on the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, but were never put in place.[18]

Grand Carré of the Tuileries

Tuileries Garden panorama

The Grand Carré (Large Square) is the eastern, open part of the Tuilieries garden, which still follows the formal plan of the Garden à la française created by André Le Nôtre in the 17th century.

The eastern part of the Grand Carré, surrounding the round pond, was the private garden of the king under Louis Philippe and Napoleon III, separated from the rest of the Tuileries by a fence.

Most of the statues in the Grand Carré were put in place in the 19th century.

- Nymphe (1866) and Diane Chasseresse (Diana the Huntress) (1869) by Louis Auguste Lévêque, which mark the beginning of the central allée which runs east-west through the park.

- Tigre terrassant un crocodile (Tiger overwhelming a crocodile) (1873) and Tigresse portant un paon à ses petits (Tigress bringing a peacock to her young) (1873), both by Auguste Cain, by the two small round ponds.

The large round pond is surrounded by statues on themes from antiquity, allegory, and ancient mythology. Statues in violent poses alternate with those in serene poses. On the south side, starting from the east entrance of the large round pond, they are:

On the north side, starting at the west entrance to the pond, they are:

Le Grand Couvert of the Tuileries

The Grand Couvert is the part of the garden covered with trees. The two cafes in the Grand Couvert are named after two famous cafes once located in the garden; the café Very, which had been on the terrace des Feuiillants in the 18th–19th century; and the café Renard, which in the 18th century had been a popular meeting place on the western terrace.

The Grand Couvert also contains the two exedres, low curving walls built to display statues, which survived from the French Revolution. They were built in 1799 by Jean Charles Moreau, part of a larger unfinished project designed by painter Jacques-Louis David in 1794. They are now decorated with plaster casts of moldings on mythological themes from the park of Louis XIV at Marly.

The Grand Couvert contains a number of important works of the 20th century and contemporary sculpture, including:

- L’Échiquier, Grand,(1959) by Germaine Richier

- La Grande Musicienne, (1937) by Henri Laurens

- Personnages III (1967) by Étienne Martin

- Primo Piano II (1962) by David Smith

- Confidence (2000) by Daniel Dezeuze

- Force et Tendresse (1996) by Eugène Dodeigne

- L’Ami de personne, (1999) by Erik Dietman

- Manus Ultimus, (1997) by Magdalena Abakanowicz

- Arbre des voyelles, (2000) by Giuseppe Penone

- Brushstroke Nude (1993) by Roy Lichtenstein

- Un, deux, tros, nous (2000) by Anne Rochette

- Jeanette, (about 1933), Paul Belmondo

- Apollon, (about 1933), Paul Belmondo

Orangerie, Jeu de Paume, and West Terrace of the Tuileries

Westernmost portion of the Tuileries Garden

Claude Monet,

Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies) 1920–26, oil on canvas, 86.2 × 237 in. (219 × 602 cm) in the Orangerie

The Orangerie (Musée de l’Orangerie), at the west end of the garden close to the Seine, was built in 1852 by the architect Firmin Bourgeois. Since 1927 it has displayed the series Water Lilies by Claude Monet. It also displays the Walter-Guillaume collection of Impressionist painting

On the terrace of the Orangerie are four works of sculpture by Auguste Rodin: Le Baiser (1881–1898); Eve (1881) and La Grande Ombre (1880) and La Meditation avc bras (1881–1905). It also has a modern work, Grand Commandement blanc (1986) by Alain Kirili.

The Jeu de Paume (Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume) was built in 1861 was the architect Viraut, and enlarged in 1878. In 1927 it became an annex of the Luxembourg Palace Museum for the display of contemporary art from outside France. During the German Occupation of World War II, from 1940 to 1944, it was used by the Germans as a depot for storing art they stole or expropriated from Jewish families. From 1947 until 1986, it served as the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which held many important Impressionist works now housed in the Musée d’Orsay. Today, the Jeu de Paume is used for exhibits of modern and contemporary art.

On the terrace in front of the Jeu de Paume is a work of sculpture, Le Bel Costumé (1973) by Jean Dubuffet.

Sculptures

Mercury riding Pegasus, (1701–02) by Antoine Coysevox (1640–1720). Originally at Marly, moved to the Tuileries in 1719 and placed at the west gate of the garden. In 1986 the original of marble was moved to the Louvre and replaced by a copy.

Nymphe by Louis Auguste Lévêque, (1866). In the Grand Carré, at the beginning of the Grand Allée.

Theseus and the Minotaur (1821) by Jules Ramey, in the Grand Carré

- Bibliography

- Allain, Yves-Marie and Janine Christiany, L’art des jardins en Europe, Citadelles et Mazenod, Paris, 2006.

- Hazlehurst, F. Hamilton, Gardens of Illusion: The Genius of André Le Nostre, Vanderbilt University Press, 1980. (ISBN 9780826512093)

- Impelluso, Lucia, Jardins, potagers et labyrinthes, Hazan, Paris, 2007.

- Jacquin, Emmanuel, Les Tuileries, Du Louvre à la Concorde, Editions du Patrimoine, Centres des Monuments Nationaux, Paris. (ISBN 978-2-85822-296-4)

- Jarrassé, Dominique, Grammaire des Jardins Parisiens, Parigramme, Paris, 2007. (ISBN 978-2-84096-476-6)

- Prevot, Philippe, Histoire des jardins, Editions Sud Ouest, 2006.

- Wenzler, Claude, Architecture du jardin, Editions Ouest-France, 2003.

- See also

- History of Parks and Gardens of Paris

- Sources and citations

- Emmanuel Jacquin, Les Tuileries Du Louvre à la Concorde.

- Jacquin, Les Tuileries — Du Louvre à la Concorde, p. 4.

- Jacquin, p. 6

- Jacquin, p. 10

- Jacquin p. 15

- Jarrassé, Grammaire des Jardins Parisiens, p. 51.

- Jarrassé, p. 47

- The statues in the park now are copies; the originals are in the Louvre.

- Chairs were still being rented for a small sum until 1970.

- Jacquin, p. 24.

- Jacquin, p. 25

- The two exedres have been restored, with plaster copies of the original statues.

- Jacquin, p. 26–27

- 1900 Summer Olympics official report. p. 16. Accessed 14 November 2010. (in French)

- Jacquin, p. 41

- Jacquin, p. 42–43

- Jarrassé, p. 49

- Jacquin, p. 46