The Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte is a baroque French château located in Maincy, near Melun, 55 kilometres (34 mi) southeast of Paris in the Seine-et-Marne département of France.

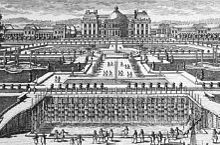

Constructed from 1658 to 1661 for Nicolas Fouquet, Marquis de Belle Île, Viscount of Melun and Vaux, the superintendent of finances of Louis XIV, the château was an influential work of architecture in mid-17th-century Europe. At Vaux-le-Vicomte, the architect Louis Le Vau, the landscape architect André le Nôtre, and the painter-decorator Charles Le Brun worked together on a large-scale project for the first time. Their collaboration marked the beginning of the “Louis XIV style” combining architecture, interior design and landscape design. The garden’s pronounced visual axis is an example of this style.[1]

Contents

History

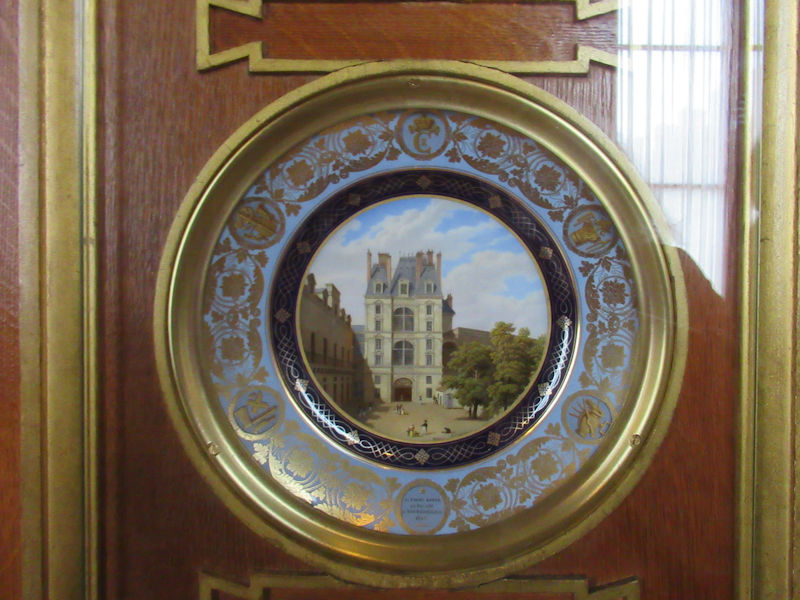

Once a small château between the royal residences of Vincennes and Fontainebleau, the estate of Vaux-le-Vicomte was purchased in 1641 by Nicolas Fouquet, an ambitious 26-year-old member of the Parlement of Paris. Fouquet was an avid patron of the arts, attracting many artists with his generosity.

When Fouquet became King Louis XIV’s superintendent of finances in 1657, he commissioned Le Vau, Le Brun and Le Nôtre to renovate his estate and garden to match his grand ambition. Fouquet’s artistic and cultivated personality subsequently brought out the best in the three.[2]

To secure the necessary grounds for the elaborate plans for Vaux-le-Vicomte’s garden and castle, Fouquet purchased and demolished three villages. The displaced villagers were then employed in the upkeep and maintenance of the gardens. It was said to have employed 18 thousand workers and cost as much as 16 million livres.[3]

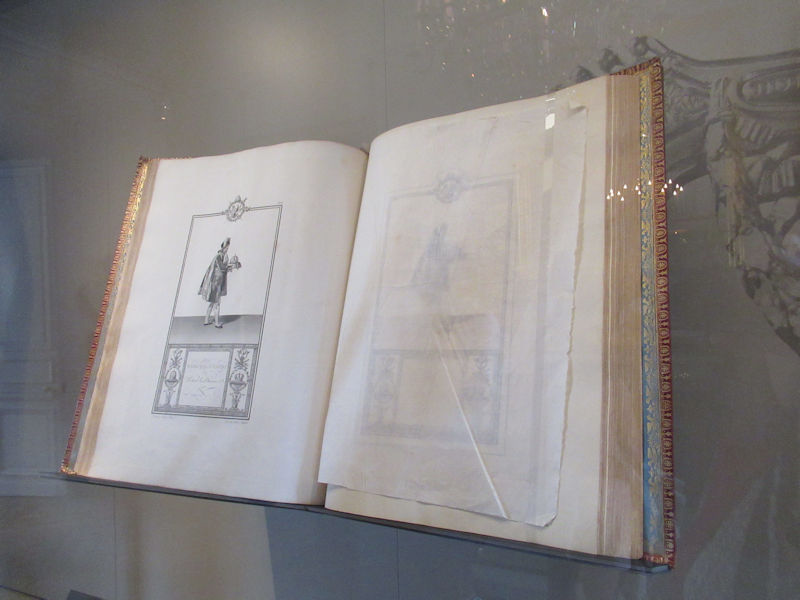

The château and its patron became for a short time a focus for fine feasts, literature and arts. The poet Jean de La Fontaine and the playwright Molière were among the artists close to Fouquet. At the inauguration of Vaux-le-Vicomte, a Molière play was performed, along with a dinner event organized by François Vatel and an impressive firework show.[4]

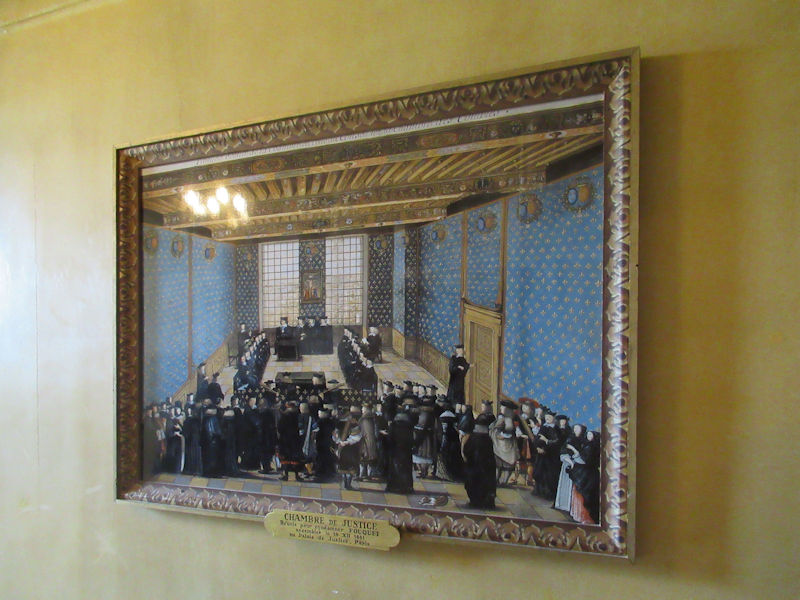

Fête and arrest

The château was lavish, refined and dazzling to behold, but those characteristics proved tragic for its owner: the king had Fouquet arrested shortly after a famous fête that took place on 17 August 1661, where Molière‘s play ‘Les Fâcheux’ debuted.[5] The celebration had been too impressive and the superintendent’s home too luxurious. Fouquet’s intentions were to flatter the king: part of Vaux-le-Vicomte was actually constructed specifically for the king, but Fouquet’s plan backfired. Jean-Baptiste Colbert led the king to believe that his minister’s magnificence was funded by the misappropriation of public funds. Colbert, who then replaced Fouquet as superintendent of finances, arrested him.[6] Later, Voltaire was to sum up the famous fête: “On 17 August, at six in the evening Fouquet was the King of France: at two in the morning he was nobody.” La Fontaine wrote describing the fête and shortly afterwards penned his Elégie aux nymphes de Vaux.

After Fouquet

After Fouquet was arrested and imprisoned for life and his wife exiled, Vaux-le-Vicomte was placed under sequestration. The king seized, confiscated or purchased 120 tapestries, the statues and all the orange trees from Vaux-le-Vicomte. He then sent the team of artists (Le Vau, Le Nôtre and Le Brun) to design what would be a much larger project than Vaux-le-Vicomte, the palace and gardens of Versailles.

Madame Fouquet recovered her property 10 years later and retired there with her eldest son. In 1705, after the death of her husband and son, she decided to put Vaux-le-Vicomte up for sale.[2]

Recent history

Marshal Claude Louis Hector de Villars became the new owner without first seeing the chateau. In 1764, the Marshal’s son sold the estate to the Duke of Praslin, whose descendants maintained the property for over a century. It is sometimes mistakenly reported that the château was the scene of a murder in 1847, when Charles de Choiseul-Praslin killed his wife in her bedroom, but he did so not at Vaux-le-Vicomte but at his Paris residence.[2]

In 1875, after thirty years of neglect, the estate was sold to Alfred Sommier in a public auction. The château was empty, some of the outbuildings had fallen into ruin and the gardens were completely overgrown. Restoration and refurbishment began under the direction of the architect Gabriel-Hippolyte Destailleur, assisted by the landscape architect Elie Lainé. When Sommier died in 1908, the château and the gardens had recovered their original appearance. His son, Edme Sommier, and his daughter-in-law completed the task. His descendants continue to preserve the château, which remains privately owned by Patrice and Cristina de Vogüé, the Count and Countess de Vogüé. It is now administered by their three sons: Alexandre, Jean-Charles and Ascanio de Vogüé. Recognized by the state as a monument historique, it is open to the public regularly.[7]

Features

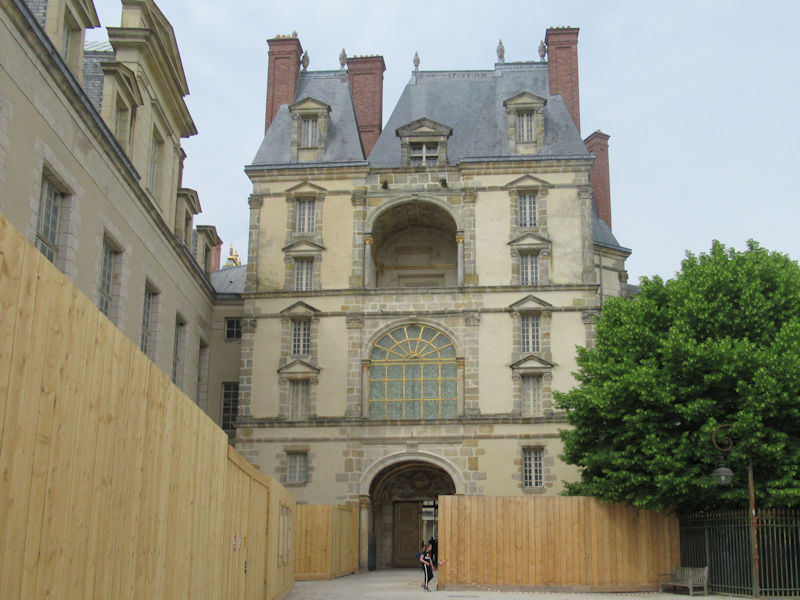

Architecture

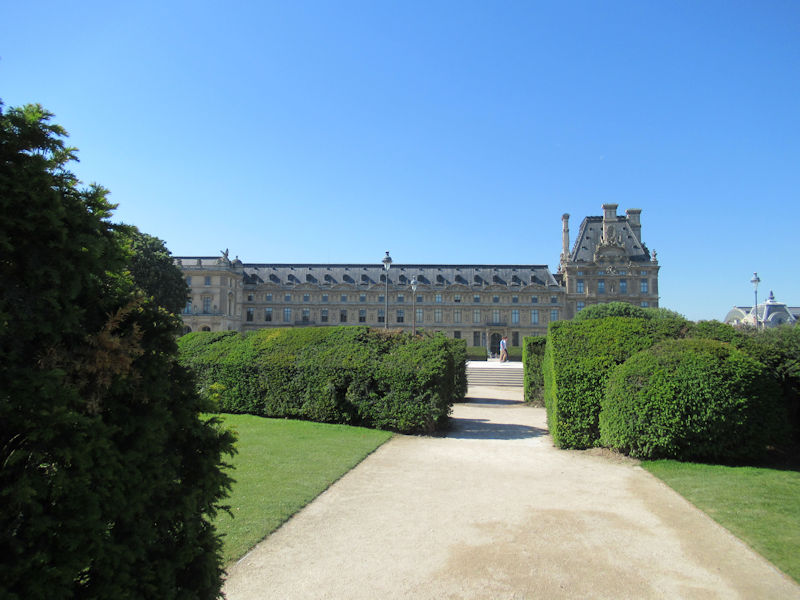

The chateau is situated near the northern end of a 1.5-km long north-south axis with the entrance front facing north. Its elevations are perfectly symmetrical to either side of this axis. Somewhat surprisingly the interior plan is also nearly completely symmetrical with few differences between the eastern and western halves. The two rooms in the centre, the entrance vestibule to the north and the oval salon to the south, were originally an open-air loggia, dividing the chateau into two distinct sections. The interior decoration of these two rooms was therefore more typical of an outdoor setting. Three sets of three arches, those on the entrance front, three more between the vestibule and the salon, and the three leading from the salon to the garden are all aligned and permitted the arriving visitor to see through to the central axis of the garden even before entering the chateau. The exterior arches could be closed with iron gates and only later were filled in with glass doors and the interior arches with mirrored doors. Since the loggia divided the building into two halves, there are two symmetrical staircases on either side of it, rather than a single staircase. The rooms in the eastern half of the house were intended for the use of the king, those in the western were for Fouquet. The provision of a suite of rooms for the king was normal practice in aristocratic houses of the time, since the king travelled frequently.[8]

Another surprising feature of the plan is the thickness of the main body of the building (corps de logis), which consists of two rows of rooms running east and west. Traditionally, the middle of the corps de logis of French chateaux consisted of a single row of rooms. Double-thick corps de logis had already been used in hôtels particuliers in Paris, including Le Vau’s Hôtel Tambonneau, but Vaux was the first chateau to incorporate this change. Even more unusual, the main rooms are all on the ground floor rather than the first floor (the traditional piano nobile). This accounts for the lack of a grand staircase or a gallery, standard elements of most contemporary chateaux. Also noteworthy are corridors in the basement and on the first floor, which run the length of house, providing privacy to the rooms they access. Up to the middle of the 17th century, corridors were essentially unknown. Another feature of the plan, the four pavilions, one at each corner of the building, is more conventional.[9]

Vaux-le-Vicomte was originally planned to be constructed in brick and stone, but after the mid-century, as the middle classes began to imitate this style, aristocratic circles began using stone exclusively. Rather late in the design process, Fouquet and Le Vau switched to stone, a decision that may have been influenced by the use of stone at François Mansart’s Château de Maisons. The service buildings flanking the large avant-cour to the north of the house remained in brick and stone, and other structures preceding them were in rubble-stone and plaster, a social ranking of building materials that would be common in France for a considerable length of time thereafter.[9]

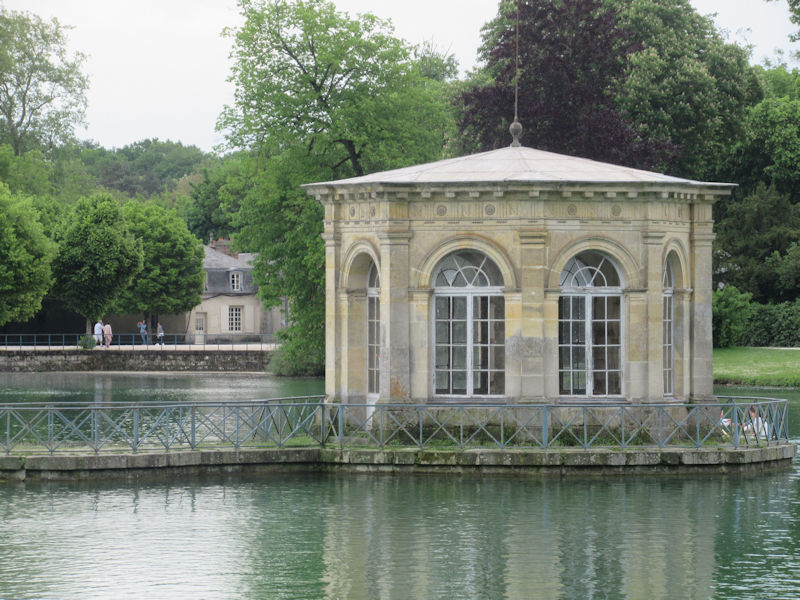

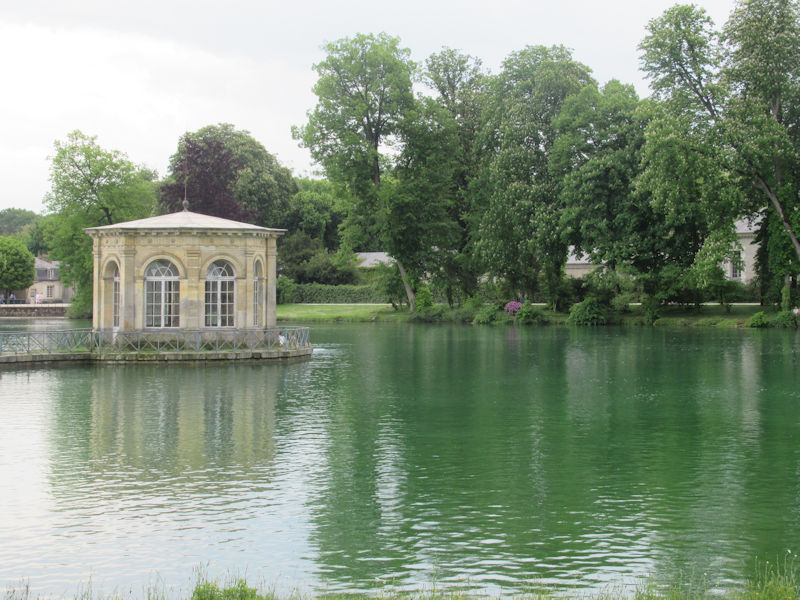

The main chateau is constructed entirely on a moated platform, reached via two bridges, both aligned with the central axis and placed on the north and south sides. The moat is a picturesque holdover from medieval fortified residences, and is again a feature that Le Vau may have borrowed from Maisons. The moat at Vaux may also have been inspired by the previous chateau on the site, which Le Vau’s work replaced.[9]

The bridge over the moat on the north side leads from the avant-cour to an ample forecourt, flanked by raised terraces on either side, a layout evoking the cour d’honneur of older aristocratic houses in which the entrance court was enclosed by anterior wings, typically housing kitchens and domestic quarters. Le Vau’s terraces even terminate in larger squares suggesting former pavilions. In more modern residences, like Vaux, it had become the custom to put these facilities in the basement, so these structures were no longer needed. This U-shaped plan of the house with the terraces is a device that again recalls Maisons, where Mansart intended “to indicate that his château was conceived in a noble tradition of French design while at the same time emphasizing its modernity in comparison to predecessors.”[10]

The entrance front of the main chateau is characteristically French, with the two lateral pavilions flanking a central avant-corps, again reminiscent of Mansart’s work at Maisons. Le Vau supplements these with two additional receding volumes between the pavilions and the central mass. All of these elements are further emphasized with steep pyramidal caps. Such steep roofs were inherited from medieval times and, like brick, were rapidly going out of fashion. Le Vau would never use them again. The overall effect at Vaux, according to Andrew Ayers, is “somewhat disparate and disorderly”.[9] Moreover, as David Hanser points out, Le Vau’s elevation violates several rules of pure classical architecture. One of the most egregious is the use of two, rather than three, bays in the lateral pavilions, resulting in the uncomfortable placement of the pediments directly over the central pilaster.[11] Ayers does concede however that, “although rather ungainly, the entrance facade at Vaux is nonetheless picturesque, in spite, or perhaps because, of its idiosyncrasies.”[12]

The garden front of the main chateau is considered more successful. The enormous, double-height Grand Salon that substantially protrudes from the corps de logis clearly dominates the southern elevation. The salon is covered by a huge slate dome surmounted with an imposing lantern and is fronted with a two-storey portico that is almost identical to one at the Hôtel Tambonneau. The use of a central oval salon is an innovation adopted by Le Vau from Italy. Although he himself had never been there, he undoubtedly knew from drawings and engravings of examples in buildings, such as the Palazzo Barberini in Rome, and had already used one to great effect at his Château du Raincy. At Le Raincy the salon spans the corps de logis and projects on both sides, but at Vaux, because of the double row of rooms, it is preceded by the vestibule on the entrance side, “thus delaying and dramatizing the visitor’s discovery of this, the centrepiece of the house.”[9] The lateral pavilions of the garden facade project only slightly but are three bays wide with traditional tall slate roofs like those on the entrance front, effectively balancing the central domed salon.[9]

Gardens

The château rises on an elevated platform in the middle of the woods and marks the border between unequal spaces, each treated in a different way. This effect is more distinctive today, as the woodlands are more mature, than it was in the seventeenth century when the site had been farmland, and the plantations were new.

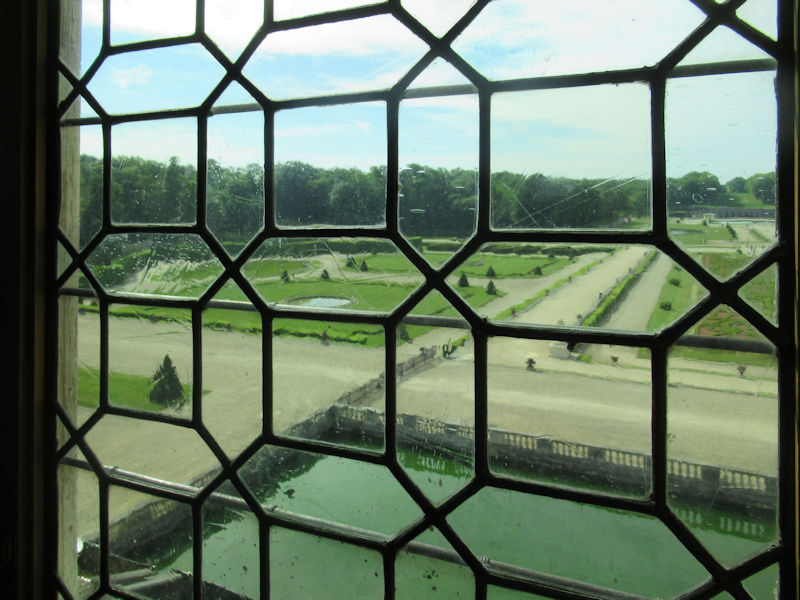

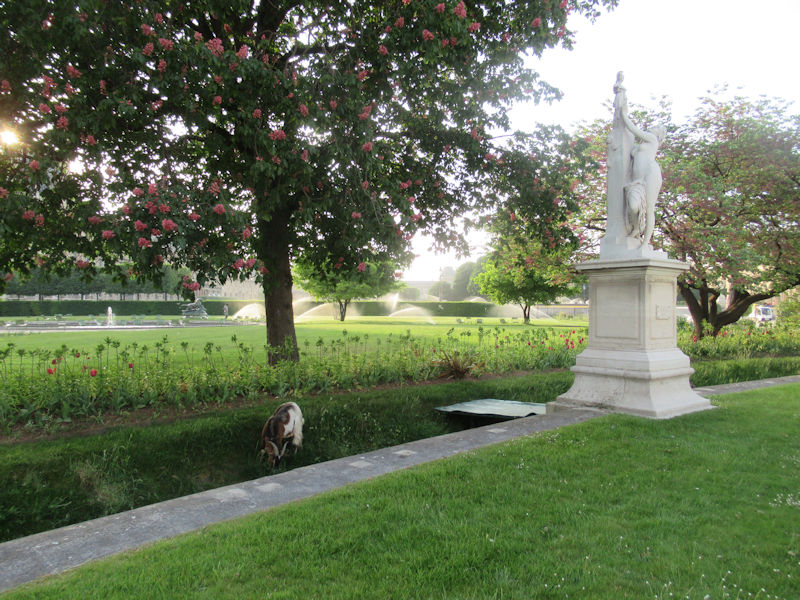

Le Nôtre’s garden was the dominant structure of the great complex, stretching nearly a mile and a half (3 km),[2] with a balanced composition of water basins and canals contained in stone curbs, fountains, gravel walks, and patterned parterres that remains more coherent than the vast display Le Nôtre was to create at Versailles.[13]

The site was naturally well-watered, with two small rivers that met in the park; the canalized bed of one forms the Grand Canal, which leads to a square basin.

Le Nôtre created a magnificent scene to be viewed from the house, using the laws of perspective. Le Nôtre used the natural terrain to his advantage. He placed the canal at the lowest part of the complex, thus hiding it from the main perspectival point of view.[14] Past the canal, the garden ascends a large open lawn and ends with the Hercules column added in the 19th century. Shrubberies provided a picture frame to the garden that also served as a stage for royal fêtes.[3]

Anamorphosis abscondita in the garden

Le Nôtre employed an optical illusion called anamorphosis abscondita (which might be roughly translated as ‘hidden distortion’) in his garden design in order to establish decelerated perspective. The most apparent change in this manner is of the reflecting pools. They are narrower at the closest point to the viewer (standing at the rear of the château) than at their farthest point; this makes them appear closer to the viewer. From a certain designed viewing point, the distortion designed into the landscape elements produces a particular forced perspective and the eye perceives the elements to be closer than they actually are. That point, for Vaux-le-Vicomte, is at the top of the stairs at the rear of the château. Standing atop the grand staircase, one begins to experience the garden with a magnificent perspectival view.[15] The anamorphosis abscondita creates visual effects, which are not encountered in nature, making the spectacle of gardens designed in this way extremely unusual to the viewer (who experiences a tension between the natural perspective cues in his peripheral vision and the forced perspective of the formal garden). The perspective effects are not readily apparent in photographs, either, making viewing the gardens in person the only way of truly experiencing them.

From the top of the grand staircase, this gives the impression that the entire garden is revealed in one single glance. Initially, the view consists of symmetrical rows of shrubbery, avenues, fountains, statues, flowers and other pieces developed to imitate nature: the elements exemplify the Baroque desire to mold nature to fit its wishes, thus using nature to imitate nature. The centrepiece is a large reflecting pool flanked by grottos holding statues in their many niches. The grand sloping lawn is not visible until one begins to explore the garden, when the viewer is made aware of the optical elements involved and discovers that the garden is much larger than it looks. Next, a circular pool, previously seen as ovular due to foreshortening, is passed and a canal that bisects the site is revealed, as well as a lower level path. As the viewer continues on, the second pool shows itself to be square and the grottos and their niched statues become clearer. However, when one walks towards the grottos, the relationship between the pool and the grottos appears awry. The grottos are actually on a much lower level than the rest of the garden and separated by a wide canal that is over half a mile (almost a kilometre) long. According to Allen Weiss, in Mirrors of Infinity, this optical effect is a result of the use of the tenth theorem of Euclid‘s Optics, which asserts that “the most distant parts of planes situated below the eye appear to be the most elevated”.

In Fouquet’s time, interested parties could cross the canal in a boat, but walking around the canal provides a view of the woods that mark what is no longer the garden and shows the distortion of the grottos previously seen as sculptural. Once the canal and grottos have been passed, the large sloping lawn is reached and the garden is viewed from the initial viewpoint’s vanishing point, thus completing the circuit as intended by Le Nôtre. From this point, the distortions create the illusion that the gardens are much longer than they actually are. The many discoveries[example needed] made as one[who?] travels through the dynamic garden contrast with the static view of the garden from the château.[15]

Use in film, television and popular culture

The house and its grounds were used as the Californian home of the main villain Hugo Drax (played by Michael Lonsdale) in the 1979 James Bond film Moonraker.[16] It can also be seen in the background in the 1998 film The Man in the Iron Mask. In addition, the château appeared in several episodes of The Revolution, which is a documentary television series about the American Revolutionary War that was broadcast by History in 2006. Australia’s Next Top Model had a fashion shoot at the chateau for its 7th Cycle (Episode 02), televised in August 2011. A confused retelling of the Vaux-le-Vicomte story was given by character Little Carmine Lupertazzi in season 4 of HBOs The Sopranos. More recently it has featured as the Palace of Versailles for BBC/Canal+ production of the TV drama series Versailles.

See also

References

- Notes

- Federic Lees, The Chateau de Vaux-le-Vicomte’, Architectural Record, Asian Institute of Architects, p.413-433

- “Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte – Vaux le Vicomte”. Vaux le Vicomte. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- “Vaux le Vicomte’s and Baroque garden design”. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Ernest C. Peixottop, Through the French Provinces, p.73

- William Driver Howarth, Molière, a Playwright and His Audience, p.43

- “Nicolas Fouquet”. Vaux le Vicomte. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- “Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte”. chateaux-france.com. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Hanser 2006, p. 274; Ayers 2004, p. 371.

- Ayers 2004, pp. 368–373.

- Ayers 2004, p. 369.

- Hanser 2006, p. 274

- Ayers 2004, p. 370.

- Beatrix Jones, Le Notre and his Gardens, Scribner’s Magazine, v.38 (1905), pp.43-55

- Leonard Benevolo, The Architecture of the Renaissance, pp.714-723

- Allen S. Weiss, Mirrors of Infinity:The French Formal Garden and 17th-Century Metaphysics, Princeton Architectural Press: New York, 1995, p.33-51

- “Moonraker (1979)”. IMDb. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Sources

- Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart; London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 978-3-930698-96-7.

- Hanser, David A. (2006). Architecture of France. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31902-0.

Click Refresh to view slides