The Bois de Boulogne is a large public park located along the western edge of the 16th arrondissement of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt and Neuilly-sur-Seine. It was created between 1852 and 1858 during the reign of the Emperor Napoleon III.

It is the second-largest park in Paris, slightly smaller than the Bois de Vincennes on the eastern side of the city. It covers an area of 845 hectares (2088 acres), which is about two and a half times the area of Central Park in New York and slightly less (88%) than that of Richmond Park in London.

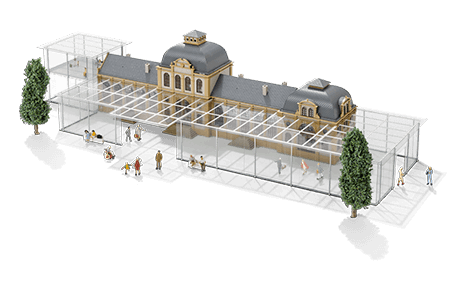

Within the boundaries of the Bois de Boulogne are an English landscape garden with several lakes and a cascade; two smaller botanical and landscape gardens, the Château de Bagatelle and the Pré-Catelan; a zoo and amusement park in the Jardin d’Acclimatation; GoodPlanet Foundation‘s Domaine de Longchamp dedicated to ecology and humanism, The Jardin des Serres d’Auteuil, a complex of greenhouses holding a hundred thousand plants; two tracks for horse racing, the Hippodrome de Longchamp and the Auteuil Hippodrome; a tennis stadium where the French Open tennis tournament is held each year; and other attractions.

For the two 1896 short films, see Bois de Boulogne (film).

History

A hunting preserve, royal châteaux, and a historic balloon flight

The Bois de Boulogne is a remnant of the ancient oak forest of Rouvray, which included the present-day forests of Montmorency, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Chaville, and Meudon. Dagobert, the King of the Franks (629-639), hunted bears, deer, and other game in the forest. His grandson, Childeric II, gave the forest to the monks of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, who founded several monastic communities there. Philip Augustus (1180–1223) bought back the main part of the forest from the monks to create a royal hunting reserve. In 1256, Isabelle de France, sister of Saint-Louis, founded the Abbey of Longchamp at the site of the present hippodrome.

The Bois received its present name from a chapel, Notre Dame de Boulogne la Petite, which was built in the forest at the command of Philip IV of France (1268–1314). In 1308, Philip made a pilgrimage to Boulogne-sur-Mer, on the French coast, to see a statue of the Virgin Mary which was reputed to inspire miracles. He decided to build a church with a copy of the statue in a village in the forest not far from Paris, in order to attract pilgrims. The chapel was built after Philip’s death between 1319 and 1330, in what is now Boulogne-Billancourt.

During the Hundred Years’ War, the forest became a sanctuary for robbers and sometimes a battleground. In 1416-17, the soldiers of John the Fearless, the Duke of Burgundy, burned part of the forest in their successful campaign to capture Paris. Under Louis XI, the trees were replanted, and two roads were opened through the forest.

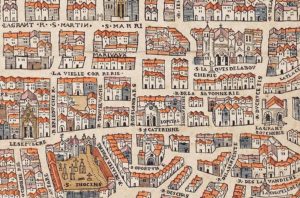

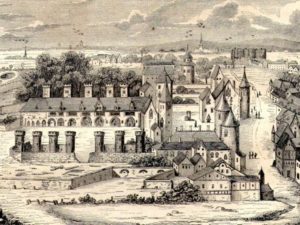

In 1526, King Francis I of France began a royal residence, the Château de Madrid, in the forest in what is now Neuilly and used it for hunting and festivities. It took its name from a similar palace in Madrid, where Francis had been held prisoner for several months. The Chateau was rarely used by later monarchs, fell into ruins in the 18th century, and was demolished after the French Revolution.

The Chateau de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne, built in 1526 by Francis I of France.

The Chateau de la Muette was the home of Queen Marguerite de Valois after her marriage was annulled by King Henry IV of France. It was demolished after the French Revolution.

Despite its royal status, the forest remained dangerous for travelers; the scientist and traveler Pierre Belon was murdered by thieves in the Bois de Boulogne in 1564.[6]

During the reigns of Henry II and Henry III, the forest was enclosed within a wall with eight gates. Henry IV planted 15,000 mulberry trees, with the hope of beginning a local silk industry. When Henry annulled his marriage to Marguerite de Valois, she went to live in the Château de la Muette, on the edge of the forest.

In the early 18th century, wealthy and important women often retired to the convent of the Abbey of Longchamp, located where the hippodrome now stands. A famous opera singer of the period, Madmoiselle Le Maure, retired there in 1727 but continued to give recitals inside the Abbey, even during Holy Week. These concerts drew large crowds and irritated the Archibishop of Paris, who closed the Abbey to the public.[7]

Louis XVI and his family used the forest as a hunting ground and pleasure garden. In 1777, the Comte d’Artois, Louis XVI‘s brother, built a charming miniature palace, the Château de Bagatelle, in the Bois in just 64 days, on a wager from his sister-in-law, Marie Antoinette. Louis XVI also opened the walled park to the public for the first time.

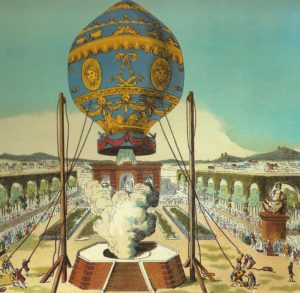

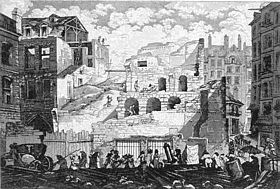

On 21 November 1783, Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d’Arlandes took off from the Chateau de la Muette in a hot air balloon made by the Montgolfier brothers. Previous flights had carried animals or had been tethered to the ground; this was the first manned free flight in history. The balloon rose to a height of 910 meters (3000 feet), was in the air for 25 minutes, and covered nine kilometers.[8]

The first free manned flight was launched by the Montgolfier Brothers from the Chateau de la Muette, on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, on November 21, 1783.

Following the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814, 40,000 soldiers of the British and Russian armies camped in the forest. Thousands of trees were cut down to build shelters and for firewood.

From 1815 until the French Second Republic, the Bois was largely empty, an assortment of bleak ruined meadows and tree stumps where the British and Russians had camped and dismal stagnant ponds.[9]

The design of the park

The Bois de Boulogne was the idea of Napoleon III, shortly after he staged a coup d’état and elevated himself from the President of the French Republic to Emperor of the French in 1852. When Napoleon III became Emperor, Paris had only four public parks – the Tuileries Gardens, the Luxembourg Garden, the Palais Royale, and the Jardin des Plantes – all in the center of the city. There were no public parks in the rapidly growing east and west of the city. During his exile in London, he had been particularly impressed by Hyde Park, by its lakes and streams and its popularity with Londoners of all social classes. Therefore, he decided to build two large public parks on the eastern and western edges of the city where both the rich and ordinary people could enjoy themselves.[10]

These parks became an important part of the plan for the reconstruction of Paris drawn up by Napoleon III and his new Prefect of the Seine, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. The Haussmann plan called for improving the city’s traffic circulation by building new boulevards; improving the city’s health by building a new water distribution system and sewers; and creating green spaces and recreation for Paris’ rapidly growing population. In 1852, Napoleon donated the land for the Bois de Boulogne and for the Bois de Vincennes, which both belonged officially to him. Additional land in the plain of Longchamp, the site of the Chateau de Madrid, the Chateau de Bagatelle, and its gardens were purchased and attached to the proposed park, so it could extend all the way to the Seine. Construction was funded out of the state budget, supplemented by selling building lots along the north end of the Bois, in Neuilly,[11]

Napoleon III was personally involved in planning the new parks. He insisted that the Bois de Boulogne should have a stream and lakes, like Hyde Park in London. “We must have a stream here, as in Hyde Park,” he observed while driving through the Bois, “to give life to this arid promenade”.[12]

The first plan for the Bois de Boulogne was drawn up by the architect Jacques Hittorff, who, under King Louis Philippe, had designed the Place de la Concorde, and the landscape architect Louis-Sulpice Varé, who had designed French landscape gardens at several famous châteaux. Their plan called for long straight alleys in patterns crisscrossing the park, and, as the Emperor had asked, lakes and a long stream similar to the Serpentine in Hyde Park.

Unfortunately, Varé failed to take into account the difference in elevation between the beginning of the stream and the end; if his plan had been followed, the upper part of the stream would have been empty, and the lower portion flooded. When Haussmann saw the partially finished stream, he saw the problem immediately and had the elevations measured. He dismissed the unfortunate Varé and Hittorff, and designed the solution himself; an upper lake and a lower lake, divided by an elevated road, which serves as a dam, and a cascade which allows the water to flow between the lakes. This is the design still seen today.[13]

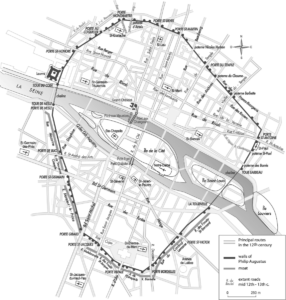

In 1853, Haussmann hired an experienced engineer from the corps of Bridges and Highways, Jean-Charles Alphand, whom he had worked with in his previous assignment in Bordeaux, and made him the head of a new Service of Promenades and Plantations, in charge of all the parks in Paris. Alphand was charged to make a new plan for the Bois de Boulogne. Alphand’s plan was radically different from the Hittorff-Varé plan. While it still had two long straight boulevards, the Allée Reine Marguerite and the Avenue Longchamp, all the other paths and alleys curved and meandered. The flat Bois de Boulogne was to be turned into an undulating landscape of lakes, hills, islands, groves, lawns, and grassy slopes, not a reproduction of but an idealization of nature. It became the prototype for the other city parks of Paris and then for city parks around the world.[14]

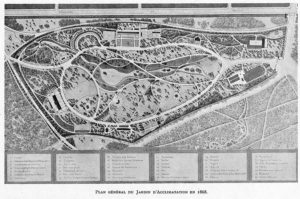

The plan of the park from 1879 shows the two straight alleys of the old Bois, and the lakes, winding lanes and paths built by Alphand.

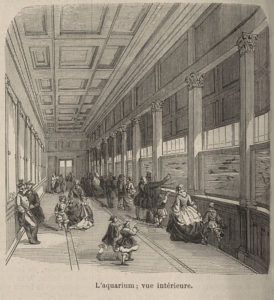

L’aquarium; vue intérieure, 1860.

The Jardin zoologique at the Bois de Boulogne included an aquarium that housed both fresh and salt water sea animals. The interior is depicted here.

The Construction of the Park

The building of the park was an enormous engineering project which lasted for five years. The upper and lower lakes were dug, and the earth piled into islands and hills. Rocks were brought from Fontainbleau and combined with cement to make the cascade and an artificial grotto.

The pumps from the Seine could not provide enough water to fill the lakes and irrigate the park, so a new channel was created to bring the water of the Ourcq River, from Monceau to the upper lake in the Blois, but this was not enough. An artesian well 586 meters deep was eventually dug in the plain of Passy which could produce 20,000 cubic meters of water a day. This well went into service in 1861.[15]

The water then had to be distributed around the park to water the lawns and gardens; the traditional system of horse-drawn wagons with large barrels of water would not be enough. A system of 66 kilometers of pipes was laid, with a faucet every 30 or 40 meters, a total of 1600 faucets.

Alphand also had to build a network of roads, paths, and trails to connect the sights of the park. The two long straight alleys from the old park were retained, and his workers built an additional 58 kilometers of roads paved with stones for carriages, 12 kilometers of sandy paths for horses, and 25 kilometers of dirt trails for walkers. As a result of Louis Napoléon’s exile in London and his memories of Hyde Park, all the new roads and paths were curved and meandering.[16]

The planting of the park was the task of the new chief gardener and landscape architect of the Service of Promenades and Plantations, Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, who had also worked with Haussmann and Alphand in Bordeaux. His gardeners planted 420,000 trees, including hornbeam, beech, linden, cedar, chestnut, and elm, and hardy exotic species, like redwoods. They planted 270 hectares of lawns, with 150 kilograms of seed per hectare, and thousands of flowers. To make the forest more natural, they brought 50 deer to live in and around the Pré-Catelan.

The park was designed to be more than a collection of pictureque landscapes; it was meant as a place for amusement and recreation, with sports fields, bandstands, cafes, shooting galleries, riding stables, boating on the lakes, and other attractions. In 1855, Gabriel Davioud, a graduate of Ecole des Beaux-Arts, was named the chief architect of the new Service of Promenades and Plantations. He was commissioned to design 24 pavilions and chalets, plus cafes, gatehouses, boating docks, and kiosks. He designed the gatehouses where the guardians of the park lived to look like rustic cottages. He had a real Swiss chalet built out of wood in Switzerland and transported to Paris, where it was reassembled on an island in the lake and became a restaurant. He built another restaurant next to the park’s most picturesque feature, the Grand Cascade. He designed artificial grottoes made of rocks and cement, and bridges and balustrades made of cement painted to look like wood. He also designed all the architectural details of the park, from cone-shaped shelters designed to protect horseback riders from the rain to the park benches and direction signs.[17]

At the south end of the park, in the Plain of Longchamp, Davioud restored the ruined windmill which was the surviving vestige of the Abbey of Longchamp, and, working with the Jockey Club of Paris, constructed the grandstands of the Hippodrome of Longchamp, which opened in 1857.

At the northern end of the park, between the Sablons gate and Neuilly, a 20-hectare section of the park was given to the Societé Imperiale zoologique d’Acclimatation, to create a small zoo and botanical garden, with an aviary of rare birds and exotic plants and animals from around the world.

In March 1855, an area in the center of the park, called the Pré-Catelan, was leased to a concessionaire for a garden and amusement park. It was built on the site of a quarry where the gravel and sand for the park’s roads and paths had been dug out. It included a large circular lawn surrounded by trees, grottos, rocks, paths, and flower beds. Davioud designed a buffet, a marionette theater, a photography pavilion, stables, a dairy, and other structures. The most original feature was the Théâtre des fleurs, an open-air theater in a setting of trees and flowers. Later, an ice skating rink and shooting gallery were added. The Pré-Catelan was popular for concerts and dances, but it had continual financial difficulties and eventually went bankrupt. The floral theater remained in business until the beginning of the First World War, in 1914.[18]

The park in the 19th and 20th century

The garden-building team brought together by Haussmann were Alphand, Barrillet-Deschamps and Davioud and went on to build The Bois de Vincennes, Parc Monceau Parc Montsouris, and the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, using the experience and aesthetics they had developed in the Bois de Boulogne. They also rebuilt the Luxembourg gardens and the gardens of the Champs- Elysees, created smaller squares and parks throughout the center of Paris, and planted thousands of trees along the new boulevards that Haussmann had created. In the 17 years of Napoleon III’s reign, they planted no less than 600,000 trees and created a total 1,835 hectares of green space in Paris, more than any other ruler of France before or since.[19]

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), which led to the downfall of Napoleon III and the long siege of Paris, the park suffered some damage from German artillery bombardment, the restaurant of the Grand Cascade was turned into a field hospital, and many of the park’s animals and wild fowl were eaten by the hungry population. In the years following, however, the park quickly recovered.

The Bois de Boulogne became a popular meeting place and promenade route for Parisians of all classes. The alleys were filled with carriages, coaches, and horseback riders, and later with men and women on bicycles, and then with automobiles. Families having picnics filled the woods and lawns, and Parisians rowed boats on the lake, while the upper classes were entertained in the cafes. The restaurant of the Pavillon de la Grand Cascade became a popular spot for Parisian weddings. During the winter, when the lakes were frozen, they were crowded with ice skaters.[20]

The activities of Parisians in the Bois, particularly the long promenades in carriages around the lakes, were often portrayed in French literature and art in the second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. Scenes set in the park appeared in Nana by Émile Zola and in Education Sentimentale by Gustave Flaubert.[21] In the last pages of Du côté de chez Swann in À la recherche du temps perdu (1914), Marcel Proust minutely described a walk around the lakes taken as a child.[22] The life in the park was also the subject of the paintings of many artists, including Eduard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Vincent van Gogh.

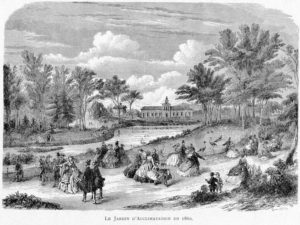

In 1860, Napoleon opened the Jardin d’Acclimatation, a separate concession of 20 hectares at the north end of the park; it included a zoo and a botanical garden, as well as an amusement park. Between 1877 and 1912, it also served as the home of what was called an ethnological garden, a place where groups of the inhabitants of faraway countries were put on display for weeks at a time in reconstructed villages from their homelands. They were mostly Sub-Saharan Africans, North Africans, or South American Indians, and came mostly from the French colonies in Africa and South America, but also included natives of Lapland and Cossacks from Russia. These exhibitions were extremely popular and took place not only in Paris, but also in Germany, England, and at the Chicago Exposition in the United States; but they were also criticized at the time and later as being a kind of “human zoo“. Twenty-two of these exhibits were held in the park in the last quarter of the 19th century. About ten more were held in the 20th century, with the last one taking place in 1931.

Le jardin d’acclimatation en 1860, gravure d’A. Provost.

In 1905, a grand new restaurant in the classical style was built in the Pré-Catelan by architect Guillaume Tronchet. Like the cafe at the Grand Cascade, it became a popular promenade destination for the French upper classes.[23]

At the 1900 Summer Olympics, the land hosted the croquet and tug of war events.[24][25] During the 1924 Summer Olympics, the equestrian events took place in the Auteuil Hippodrome.

The Bois de Boulogne was officially annexed by the city of Paris in 1929 and incorporated into the 16th arrondissement.

Soon after World War II, the park began to come back to life. In 1945, it held its first motor race after the war: the Paris Cup. In 1953, a British group, Les Amis de la France, created the Shakespeare Garden on the site of the old floral theater in the Pré-Catelan.[26]

From 1952 until 1986, the Duke of Windsor, the title granted to King Edward VIII after his abdication, and his wife, Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, lived in the Villa Windsor, a house in the Bois de Boulogne behind the garden of the Bagatelle. The house was (and still is) owned by the City of Paris and was leased to the couple. The Duke died in this house in 1972, and the Duchess died there in 1986. The lease was purchased by Mohamed al-Fayed, the owner of the Ritz Hotel in Paris. The house was visited briefly by Diana, Princess of Wales and her companion, Dodi Fayed, on 31 August 1997, the day they died in a traffic accident in the Alma tunnel.

The Villa Windsor (originally named Chateau Le Bois) is a graceful 19th-century building of 14 rooms surrounded by a large tree-filled garden. It was built around 1860 and once owned by the Renault family but the French government sequestered the property after World War II and Charles de Gaulle occupied the house in the late 1940’s.

References

- Dominique Jarrassé, Grammaire des jardins Parisiens, p. 94.

- Jarrassé, Dominique, Grammaire des jardins Parisiens, p. 94.

- Its name is commemorated in the communes of Rouvray-Catillon and Rouvray-St-Denis.

- http://www.paris.fr/loisirs/paris-au-vert/bois-de-boulogne/un-peu-d-histoire/rub_6567_stand_16149_port_14916%7CHistory Archived 7 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. of the Bois de Boulogne on the site of the City of Paris (in French).

- The current Church of Notre Dame des Menus in Boulogne-Billancourt is built on the foundation of Philip’s chapel.

- Serge Sauneron, ed. Belon, Le Voyage en Égypte de Pierre Belon du Mans 1547, (Cairo 1970) Introduction.

- | “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-07. The history of the Bois de Boulogne on the site of the City of Paris (in French).

- “U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: Early Balloon Flight in Europe”. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- Patrice de Moncan, Les jardins du Baron Haussmann, pp. 57-58.

- Patrice de Moncan, Les Jardins du Baron Haussmann, p. 9.

- J. M. Chapman and Brian Chapman, The Life and Times of Baron Haussmann: Paris in the Second Empire (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) 1957:89.

- Charles Merruau, Souvenirs de l’Hôtel de Ville de Paris, 1848-1852 (Paris 1875:37), quoted in David H. Pinkiney, “Napoleon III’s Transformation of Paris: The Origins and Development of the Idea” The Journal of Modern History 27.2 (June 1955:125-134), p. 126.

- George-Eugène Haussmann, Les Mémoires, Paris (1891), cited in Patrice de Moncan, p. 24.

- Jarrassé, p. 97.

- Patrice de Moncan, p. 60.

- Patrice de Moncan, p. 60.

- Patrice de Moncan, pp. 29-32.

- Jarrassé, p. 107 and Patrice de Moncan, pp. 64-65.

- Patrice de Moncan, p. 9.

- Patrice de Moncan, p. 65-70.

- Patrice de Moncan, p. 9.

- Jarrassé, p. 100-101.

- Jarrassé, p. 107.

- Sports-reference.com Summer Olympics Paris 28 June 1900 croquet mixed singles one-ball results. Accessed 14 November 2010.

- Sports-reference.com Summer Olympic Paris 16 July 1900 tug-of-war men’s results. Accessed 14 November 2010.

- Jarrassé, p. 107.

The grounds of the Jardin des Tuileries host three major Paris museums: the Musée de l’Orangerie, devoted to Monet’s Nymphéas and the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collections, the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which exhibits contemporary art and photography, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with its significant fashion and textiles collection as well as a more recent section devoted to advertising.

The grounds of the Jardin des Tuileries host three major Paris museums: the Musée de l’Orangerie, devoted to Monet’s Nymphéas and the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collections, the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which exhibits contemporary art and photography, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with its significant fashion and textiles collection as well as a more recent section devoted to advertising.