History

In 1925, the Museum of the Legion of Honor and Orders of Chivalry moved to the site of the stables of the palace. The Salm Hotel is classified today as historical monuments.

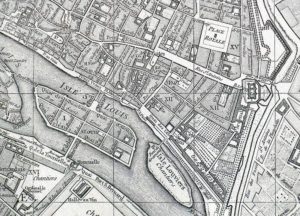

During the 17th century, French high nobility started to move from the central Marais, the then-aristocratic district of Paris where nobles used to build their urban mansions (see Hotel de Soubise), to the clearer, less populated and less polluted Faubourg Saint-Germain.

The district became so fashionable within the French aristocracy that the phrase le Faubourg has been used to describe French nobility ever since. The oldest and most prestigious families of the French nobility built outstanding residences in the area, such as the Hôtel Matignon, the Hôtel de Salm, and the Hôtel Biron.

After the Revolution many of these mansions, offering magnificent inner spaces, many receptions rooms and exquisite decoration, were confiscated and turned into national institutions. The French expression “les ors de la Republique” (literally “the golds of the Republic”), referring to the luxurious environment of the national palaces (outstanding official residences and priceless works of art), comes from that time.

During the Restauration, the Faubourg recovered its past glory as the most exclusive high nobility district of Paris and was the political heart of the country, home to the Ultra Party. After the Fall of Charles X, the district lost most of its political influence but remained the center of the French upper class‘ social life.

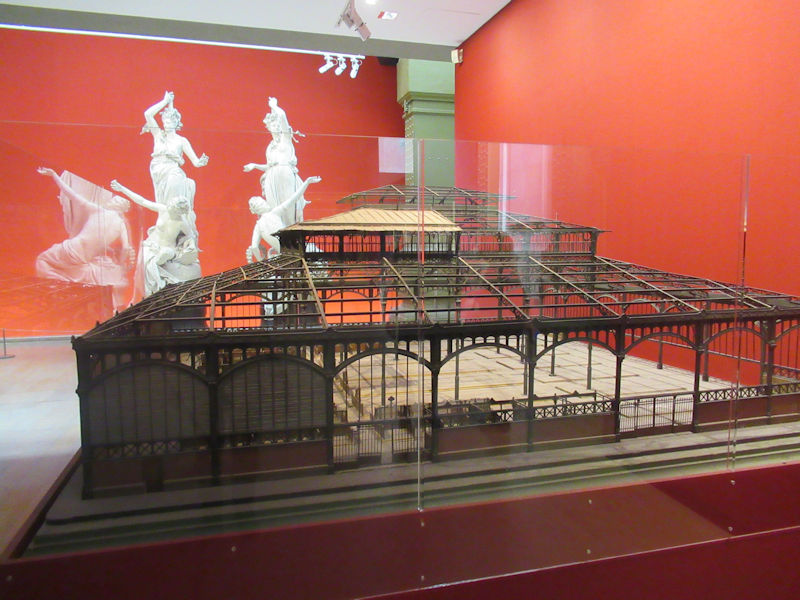

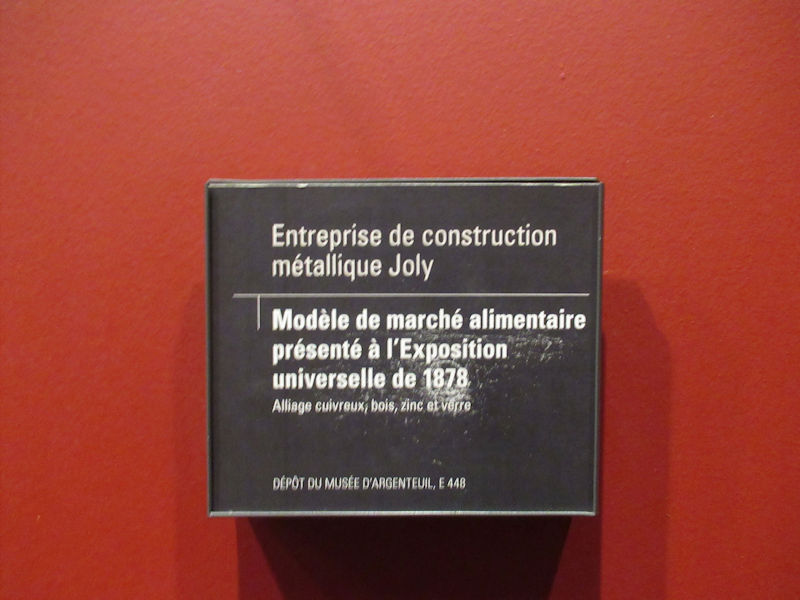

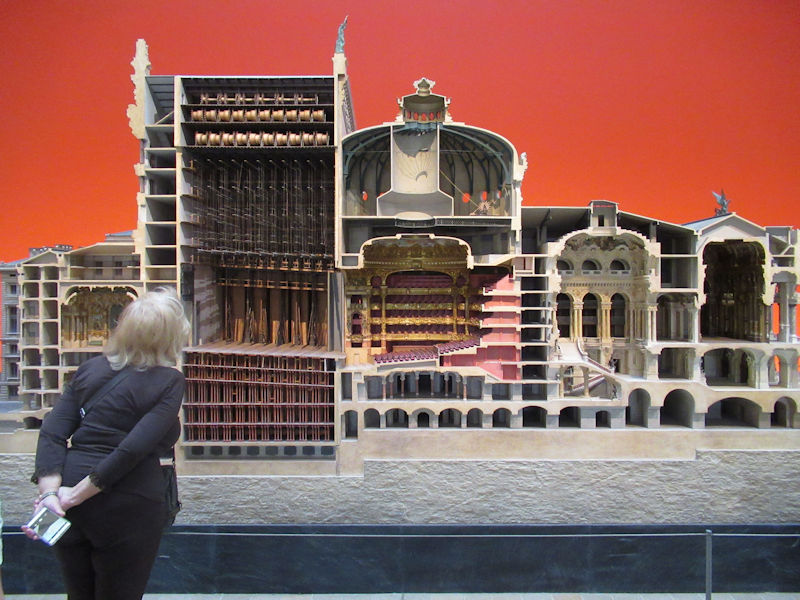

During the 19th century, the arrondissement hosted no less than five Universal Exhibitions (1855, 1867, 1878, 1889, 1900) that have immensely impacted its cityscape. The Eiffel Tower and the Orsay building have been built for these Exhibitions (respectively in 1889 and 1900).

Carnavalet Museum

The Carnavalet Museum (French: Musée Carnavalet) in Paris is dedicated to the history of the city. The museum occupies two neighboring mansions: the Hôtel Carnavalet and the former Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau. On the advice of Baron Haussmann, the civil servant who transformed Paris in the latter half of the 19th century, the Hôtel Carnavalet was purchased by the Municipal Council of Paris in 1866; it was opened to the public in 1880. By the latter part of the 20th century, the museum was full to capacity. The Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau was annexed to the Carnavalet and opened to the public in 1989.

Carnavalet Museum is one of the 14 City of Paris’ Museums that have been incorporated since January 1, 2013 in the public institution Paris Musées. It’s closed for renovation till the end of 2019.

Collections of the Carnavalet Museum

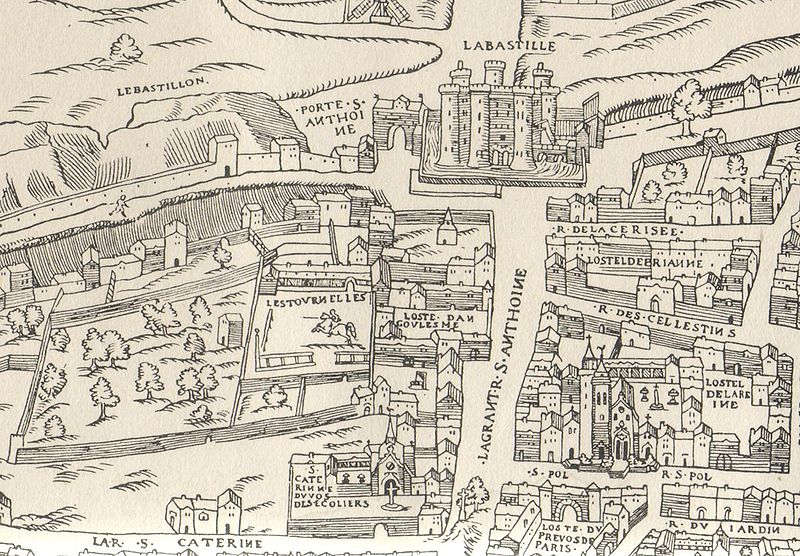

In the courtyard, a magnificent sculpture of Louis XIV, the Sun King, greets the visitor. Inside the museum, the exhibits show the transformation of the village of Lutèce, which was inhabited by the Parisii tribes, to the grand city of today with a population of 2,201,578.

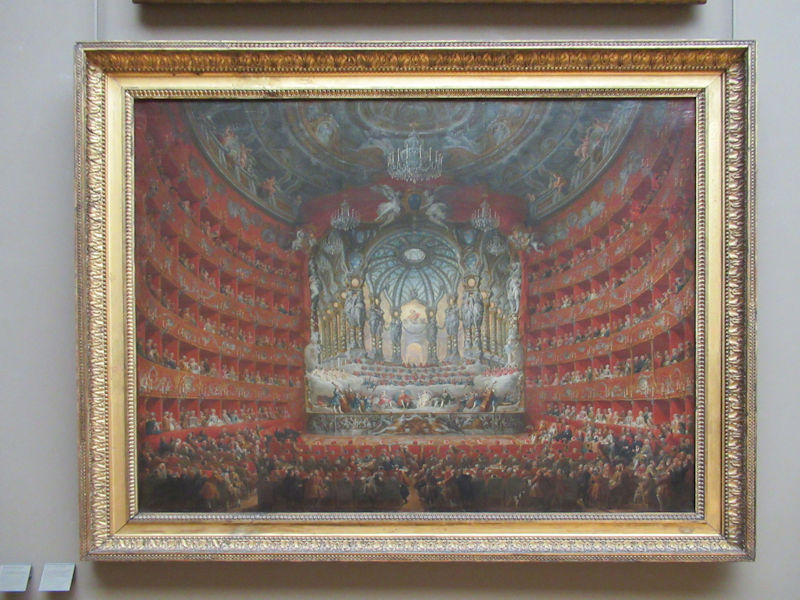

The Carnavalet houses the following: about 2,600 paintings, 20,000 drawings, 300,000 engravings and 150,000 photographs, 2,000 modern sculptures and 800 pieces of furniture, thousands of ceramics, many decorations, models and reliefs, signs, thousands of coins, countless items, many of them souvenirs of famous characters, and thousands of archeological fragments. … The period called Modern Time, which spans from the Renaissance until today, is known essentially by the vast amount of images of the city. … There are many views of the streets and monuments of Paris from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, but there are also many portraits of characters who played a role in the history of the capital and works showing events which took place in Paris, especially the many revolutions which stirred the capital, as well as many scenes of the daily life in all the social classes.

Lutetia

- Long narrow canoes made from a single tree trunk (pirogues), dating back long before the first written description of the village (known at the time as Lutèce) in A.D. 52 in Julius Caesar’s De bello Gallico

- A beautiful fourth-century bottle used for perfume, wine, or honey

The Medieval city

- An ornate chest from the 13th century, which probably came from the royal Abbey of Saint Denis

- A well-preserved 14th-century sculpture of the head of the Virgin Mary, peaceful and contemplative, despite the tumultuous events that decimated the city at that time: the Hundred Years’ War and the Great Plague of 1348

The Renaissance and Wars of Religion

- Paintings from the 16th century depicting famous men and women of the time, including Francis I, Catherine de’ Medici, and Henry IV.

- A painting of the Pont Neuf in about 1660 showing Parisians on horseback or on foot. A vendor is showing his wares to a crowd of interested on-lookers, and a man is walking hunched over with a bundle on his back.

- Several paintings of Madame de Sévigné, who was considered the most beautiful woman in Paris.

The French Revolution

- The famous uncompleted painting by Jacques-Louis David, The Tennis Court Oath (1789), portraying a pivotal event in French history when members of the National Assembly swore an emotional oath that they would not disband until they had passed a “solid and equitable Constitution.“ This event is often regarded as the beginning of the French Revolution.

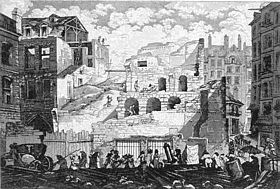

- Paintings showing the people’s revenge on the Bastille, a dungeon that had become “a symbol of the arbitrariness of royal power.”

- Paintings or sculptures of the famous actors in the drama of the Revolution, including Mirabeau, Danton, Robespierre, and the royal family.

- A painting of death by guillotine at the Place de la Révolution, by Pierre-Antoine Demauchy: the fate that struck King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, the Royalists, the Girondins, the Hébertists, the Dantonists, Robespierre and his followers, and many others.

- Personal effects belonging to Marie-Antoinette.

- A paper on which Robespierre had partially written his signature when he was seized by soldiers of the National Convention.

Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century

- Napoleon’s favorite case of toiletries

- Paintings of early-19th-century Paris

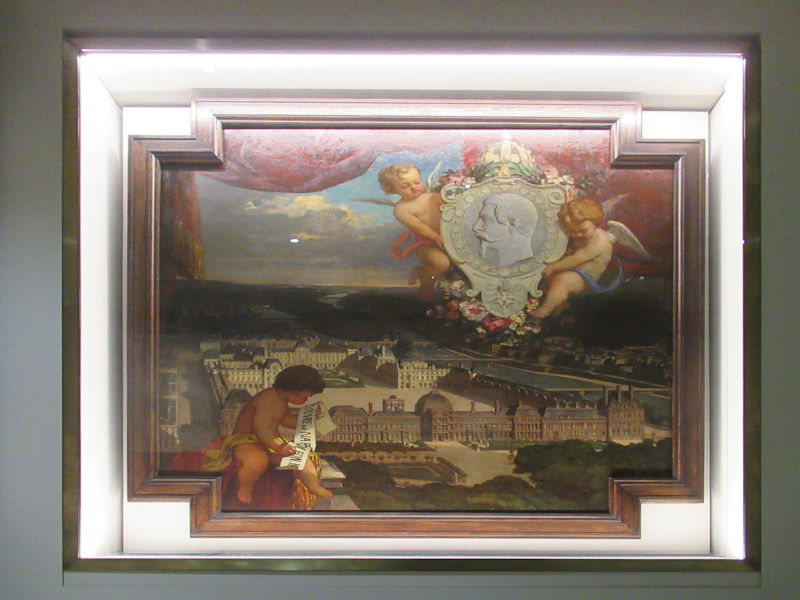

- A painting depicting one of the most important moments of the July Revolution: The Seizing of the Louvre, 29 July 1830, by Jean-Louis Bézard

- Marvelous sculptures of Parisians of the time, some realistic portrayals, others caricatures, by Jean-Pierre Dantan

- The ornate cradle of the imperial prince, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, son of the Emperor Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie

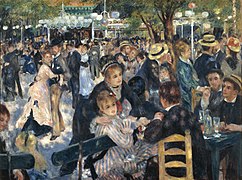

- Illustrated posters from the Belle Epoque

- Realistic paintings of late 19th-century Paris.

- A gold watch-chronometer that belonged to Émile Zola

- A painting of the construction of the Statue of Liberty, which was shipped to the United States in pieces.

- Paintings of the Exposition Universelle, including one of the Eiffel Tower, which was specifically built for this event. It was used in the 1970 Walt Disney animated film “Aristocats“.

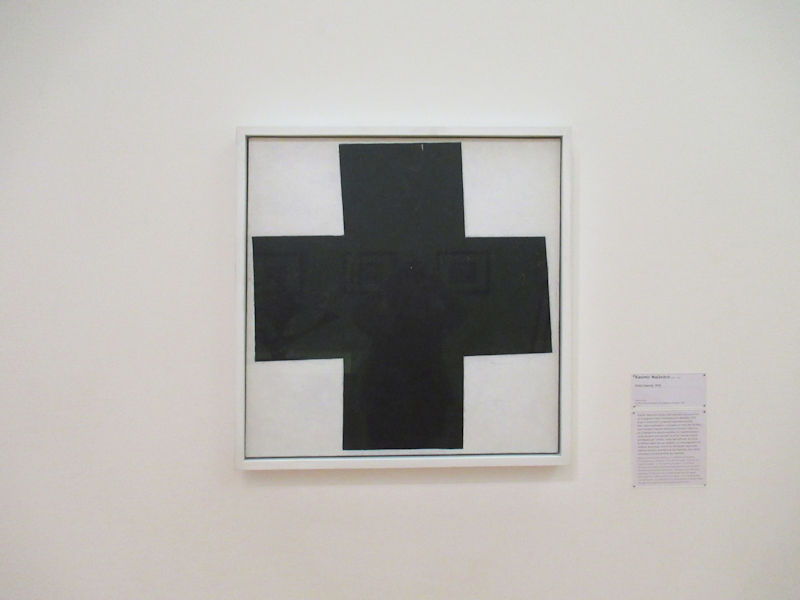

Paris in the twentieth century

- A reconstruction, with original furniture, of the room where Marcel Proust wrote In search of lost time

- Photographs of 20th-century Paris by Eugène Atget and Henri Cartier-Bresson

- A stylized painting of a crowded bistro of the mid-1900s, by the naturalized Japanese artist, Leonard Foujita

- A photograph in daguerreotype, The Forum of the Halles, taken by two American photographers in 1989 for an exhibit at the Carnavalet celebrating the 150th anniversary of the invention of photography

The present buildings

- Hôtel de Carnavalet

In 1548, Jacques des Ligneris, President of the Parliament of Paris, ordered the construction of the mansion that came to be known as the Hôtel Carnavalet; construction was completed about 1560. In 1578, the widow of Francois de Kernevenoy, a Breton whose name was rendered in French as Carnavalet, purchased the building. In 1654, the mansion was bought by Claude Boislève, who commissioned the well-known architect, François Mansart, to make extensive renovations. Madame de Sévigné, famous for her letter-writing, lived in the Hôtel Carnavalet from 1677 until her death in 1696.

- Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau

The Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau was also built in the middle of the 16th century. It was originally known as the Hôtel d’Orgeval. It was purchased by Michel Le Peletier and passed on eventually to his grandson, Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau was a representative of the nobility in the Estates-General of 1789. In 1793, Le Peletier voted for the execution of Louis XVI, and was murdered, in revenge for his vote, the same day of the execution of the king on January 20, 1793.

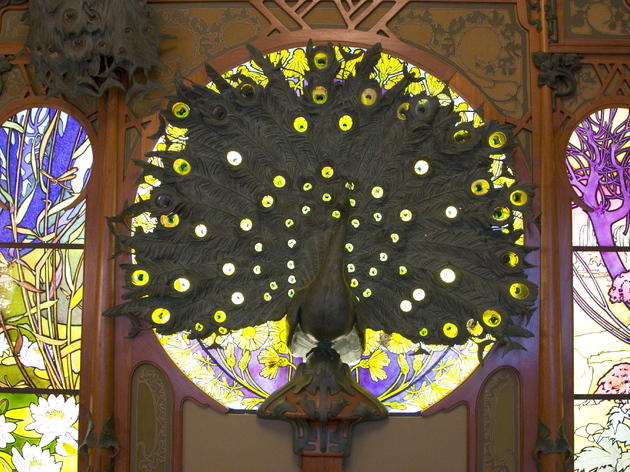

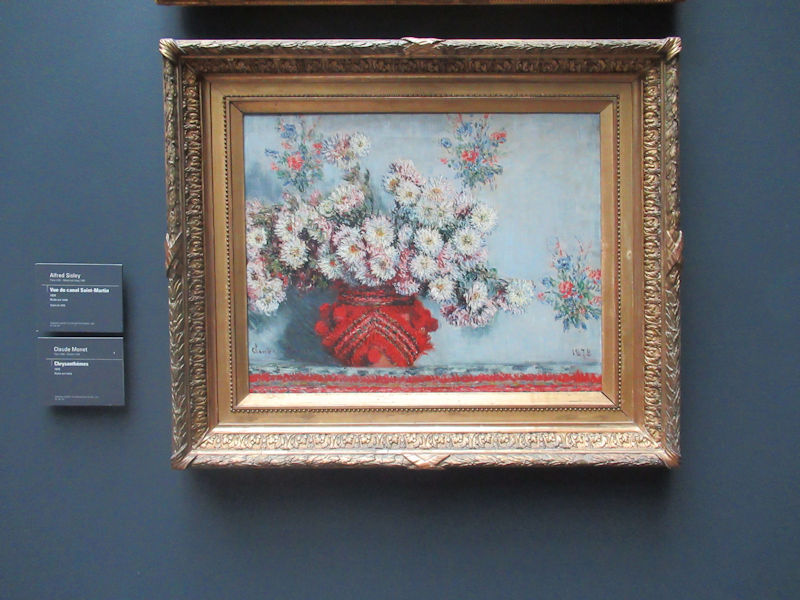

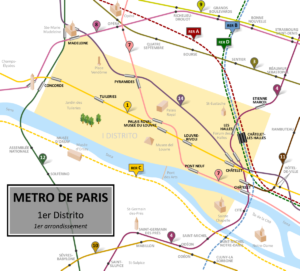

The grounds of the Jardin des Tuileries host three major Paris museums: the Musée de l’Orangerie, devoted to Monet’s Nymphéas and the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collections, the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which exhibits contemporary art and photography, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with its significant fashion and textiles collection as well as a more recent section devoted to advertising.

The grounds of the Jardin des Tuileries host three major Paris museums: the Musée de l’Orangerie, devoted to Monet’s Nymphéas and the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collections, the Musée du Jeu de Paume, which exhibits contemporary art and photography, and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs with its significant fashion and textiles collection as well as a more recent section devoted to advertising.